Rely on old Southern women to bring up two things at parties: personal ailments and how they are related to royalty. My grandmother routinely swears our kin hail from the ancient kings of Brittany and my friend’s grandmother often claims her folk go back to Charlemagne. That hunger they share for the colorful and exotic, for embellishing personal story with epic histories, lies at the root of Mary Helen Stefaniak’s The Cailiffs of Baghdad, Georgia (W.W. Norton). It’s no wonder that young Gladys Cailiff believes that the long-ago Caliphs of Baghdad have ties to the Cailiffs of Georgia, or that her brother Force is an exiled Arabian prince who was swapped at birth. Stefaniak’s tale of how Threestep, Georgia, transforms into Baghdad, Georgia, by the hand of one willful woman follows the long-standing tradition of Southern stories that contain an undercurrent of nobility.

Rely on old Southern women to bring up two things at parties: personal ailments and how they are related to royalty. My grandmother routinely swears our kin hail from the ancient kings of Brittany and my friend’s grandmother often claims her folk go back to Charlemagne. That hunger they share for the colorful and exotic, for embellishing personal story with epic histories, lies at the root of Mary Helen Stefaniak’s The Cailiffs of Baghdad, Georgia (W.W. Norton). It’s no wonder that young Gladys Cailiff believes that the long-ago Caliphs of Baghdad have ties to the Cailiffs of Georgia, or that her brother Force is an exiled Arabian prince who was swapped at birth. Stefaniak’s tale of how Threestep, Georgia, transforms into Baghdad, Georgia, by the hand of one willful woman follows the long-standing tradition of Southern stories that contain an undercurrent of nobility.

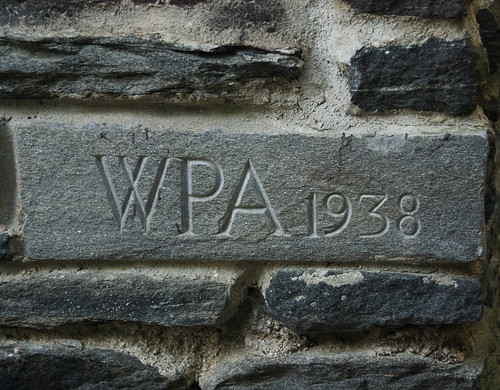

The novel opens with Gladys Cailiff’s indomitable voice. In 1938, when world traveler Grace Spivey arrives in Threestep, Georgia, to teach school, Gladys becomes one of her pupils. Helped by Gladys’s African American neighbor, Theo Boykin, Grace stirs up trouble with a progressive agenda to desegregate education and challenge local authority. Young Gladys Cailiff reports Grace’s revolutionary antics with plenty of asides and tangential anecdotes about her family and town. Her first-person reminiscence resonates with Southern charm. When a local legend stops by the Cailiff house, Gladys explains that having him “at the table was like having FDR or Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., drop by – someone you believed existed but never expected to see in the flesh.” Her self-deprecating humor includes and acclimates a modern audience to a setting utterly foreign from the world most of us remember. Gladys jokes:

The novel opens with Gladys Cailiff’s indomitable voice. In 1938, when world traveler Grace Spivey arrives in Threestep, Georgia, to teach school, Gladys becomes one of her pupils. Helped by Gladys’s African American neighbor, Theo Boykin, Grace stirs up trouble with a progressive agenda to desegregate education and challenge local authority. Young Gladys Cailiff reports Grace’s revolutionary antics with plenty of asides and tangential anecdotes about her family and town. Her first-person reminiscence resonates with Southern charm. When a local legend stops by the Cailiff house, Gladys explains that having him “at the table was like having FDR or Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., drop by – someone you believed existed but never expected to see in the flesh.” Her self-deprecating humor includes and acclimates a modern audience to a setting utterly foreign from the world most of us remember. Gladys jokes:

[Grace Spivey] told a cheery blue-suited woman from the WPA that she wanted to bring democracy and education to the poorest, darkest, most remote and forgotten part of America. They sent her to Threestep, Georgia.

Taking readers beyond a broader understanding of Southern U.S. history, Gladys guides us through the particulars of everyday life in Threestep, where its inhabitants operate under a different set of cultural norms and expectations.

As an outsider unable to accept Threestep’s status quo, Grace Spivey holds the central narrative focus for much of the book. While her motives sound altruistic, she proves to be a selfish, self-involved woman who pushes her own agenda on the small town without much regard for consequences. Characters gain significance through their relationships to Grace, whose influence is far-reaching and occasionally disastrous. Though Grace provides the backbone of the first half of the novel, she drops out in the second half leaving readers to wonder what happened to her. Later, someone tells Gladys that Grace never settled down or stopped traveling, but because Gladys “never sees her face again,” neither does the reader.

Because Grace fuels so much of the early action, we miss her presence in the latter half like we’d miss an eccentric aunt who, for no apparent reason, the family never mentions again. Grace’s memory does live on in a few items she leaves behind—a typewriter and her copy of The Thousand and One Nights—but her lasting legacy is the Annual Baghdad Bazaar, a themed county fair inspired by her Middle Eastern travels. More than anything else, the Bazaar holds the episodic plot together and incites the shift of communal identity from Threestep to Baghdad.

When the community decorates the town for Miss Spivey’s first bazaar, Stefaniak captures the moment of transformation as people wander up and down the main street in open-mouthed amazement. Mixing the weird with the mundane, the locals don turbans and lead camels through town, transforming Threestep into a delightful paradise, both unexpected and familiar. The town glows with strung electric lights. False storefronts mimic the stucco and designs of ancient Mesopotamia with signs rewritten in Arabic. Traditional small-town contests, such as a shooting game and a cakewalk, exist alongside camel rides and a play based on “Alaeddin and His Magical Lamp.” When a camel goes into labor, interrupting the town play, Gladys gives a lush picture of the community coming together in its new identity:

The scene was almost biblical. You had the straw, and the camels, and halos of yellow light around everybody from the lanterns hanging on hooks near the stall. Uncle Mack looked like a Nativity scene shepherd in his Bedouin robe and headdress, and he was soon joined in the stall by horse doctor Billy Bonner, who, in the fancy pants and turban of the Vizier, was a dead ringer for one of the Three Kings. Then my sister May came along in her midnight-blue robe and veil. All she would have needed to complete the picture was a baby in her arms. It was amazing how quiet everybody was. I believe folks did feel like they were in church at Christmastime.

Gladys appropriates each foreign element, from the Bedouin robe to the midnight-blue veil, and fashions it into a familiar scene of the nativity. Her attention to the resonance between old and new grounds the more outlandish events of the story.

The second half of Stefaniak’s story transforms from a small-town mode of yarn weaving to the mysterious, epic mode of The Thousand and One Nights. It’s a bold decision, one that may give readers pause. It parallels the transformation of the town from Threestep to Baghdad, but Stefaniak paints her characters and setting so richly in the first part, readers may miss their company.

Gladys’s sister May, who played Scheherazade in the town production of “Alaeddin,” tells the story of Grace Spivey’s trip to Baghdad, a set of tales that open like a set of nesting dolls. She recites these stories to divert the community from a catastrophe, much like the Scheherazade of legend told a succession of stories to distract her husband from murdering her in the morning. As the tales in May’s recounting unfold, they divert the reader as well, but town’s worries never leave the pages entirely. May’s “feat of storytelling” links Threestep to the larger, ancient world and provides a way for the community to trace their lineage to grander heights.

As the narrative moves further and further away from the terrain of Threestep, what is important to the novel as a whole becomes murky. Gladys’s narration reads best from a distance, unclouded by the ignorance of her younger self, or her habit of coyly slipping into third person. The frame—Gladys young, now old—allows Stefaniak to write about the past with modern sensibilities intact, but the first-person narration leaves some loose threads. As in life itself, several subplots remain unresolved, and Stefaniak defies that readerly desire for resolution when Gladys says that she is “now of an age where we have to face the possibility that some questions may go unanswered.”

As the narrative moves further and further away from the terrain of Threestep, what is important to the novel as a whole becomes murky. Gladys’s narration reads best from a distance, unclouded by the ignorance of her younger self, or her habit of coyly slipping into third person. The frame—Gladys young, now old—allows Stefaniak to write about the past with modern sensibilities intact, but the first-person narration leaves some loose threads. As in life itself, several subplots remain unresolved, and Stefaniak defies that readerly desire for resolution when Gladys says that she is “now of an age where we have to face the possibility that some questions may go unanswered.”

If the first half of the novel is an effort to make a story true to life, the second half elevates storytelling as a diversion from life. Elements of each get interchanged as one style subverts the other. Like those who listen at Scheherazade’s feet, readers must make sense of the story for themselves—forging their own meaning when the novel provides no easy, fairy-tale resolution to the twinned nature of Threestep. Stefaniak may be aiming for exactly that reaction to her grandiose, distractible citizenry.

In modern Baghdad, interest in the Annual Baghdad Bazaar has waned and Gladys writes the manuscript to reveal the true details of the first Bazaar, particularly Grace’s role in transforming the town’s identity. Gladys, no matter how much she admired Grace’s forward thinking, must still gaze into the past to tell her story. The tension between progress and tradition never completely fades. In the end, amid the ramble of stories and grand narrative aspirations, The Cailiffs of Baghdad, Georgia belongs to the characters. It’s the people of Threestep who adopt a new identity in Baghdad and reinvent a town with its heart set on a romantic, distant past, even as they welcome change.

Further Links and Resources