Reading the second story in Jon McGregor’s This Isn’t the Sort of Thing that happens to someone like you (Bloomsbury) might lead you to assume you’ve landed in Quiet Literary Fiction. You know the type, all small moments and subtle truths – Truths, I should say – and wispy, nebulous endings: impressions, as opposed to stories. You’d be wrong. Dead wrong. Again and again and again. For this collection takes the reader in hand, big, sometimes-inexplicable things happen and you may not make it out alive. McGregor’s stories are anything but safe.

Reading the second story in Jon McGregor’s This Isn’t the Sort of Thing that happens to someone like you (Bloomsbury) might lead you to assume you’ve landed in Quiet Literary Fiction. You know the type, all small moments and subtle truths – Truths, I should say – and wispy, nebulous endings: impressions, as opposed to stories. You’d be wrong. Dead wrong. Again and again and again. For this collection takes the reader in hand, big, sometimes-inexplicable things happen and you may not make it out alive. McGregor’s stories are anything but safe.

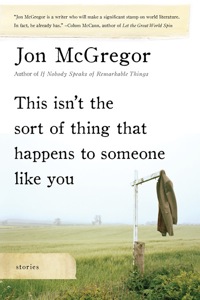

Jon McGregor, Britain’s second best short story writer (his website proclaims), has published three novels – two on the Booker long list – but this is his first story collection. Each section, and each story, bears the name of a different town in Lincolnshire (I looked them up), an agricultural county on England’s Eastern coast filled with fens, salt marshes, and earthworks built up against the sea. It’s a strangely blank landscape, not quite dreary, but overcast, obscure. You could say McGregor knows that landscape like the back of his hand, only it’s doubtful we’d know our hands so well.

The stories begin and end in medias res. Horrible events occur offstage and the reader scrabbles over hard ground, looking for rise, rock, or weir to gain a vantage point. Ironic, since Lincolnshire is noted for its flatness. The word “suspense” springs to mind. McGregor holds a black belt in misdirection. In “The Chicken and The Egg” a man fears cracking an egg to find an embryonic chicken – a study in dread. “The Last Ditch” gives a detailed plan for surviving an anticipated crisis, which has obviously fallen into the “authority’s” redacting, footnoting hands. Even at half a page, “Dig a Hole” ignites terror as a mob chants, “Dig a hole and fucking bury him.” Many narrators remain unnamed, a canny choice in a collection that forces so many decisions – which characters to trust, what Prisoner J. Disputed – on the reader.

McGregor’s surprises feel honest. You settle into the story you think he’s telling, only to discover near the end that isn’t the story you’d signed up for at all. The real magic occurs – and often – when he lets the reader fill in all the dark, dread drama. The great horror auteurs know this – anticipation is all. Cut away from the moment of violence at the last minute and you scar your viewer forever. The quick mind rabbits ahead to the worst.

In “Wires,” a sugar beet flies through a young woman’s windshield, demanding attention. We should know better. In this story, McGregor seamlessly includes technology: the girl tracks her mood in status-updates. We all – or at least 845 million of us – know exactly what she’s on about. It’s just there, as culturally universal and blasé as a toaster, no fanfare required. There has been much ham-fisted deployment of Brave New Technology in fiction; seeing it treated merely as a mental tic is refreshing.

Status update: Emily Wilkinson regrets not having signed up for breakdown insurance.

Meanwhile the reader frets: you should be worried about a hell of a lot more than that.

The stories, united by geography, cover a wild range of form and subject, but one mood prevails: loneliness. I pity the character who finds himself in McGregor’s hands, for isolation will plague him, and disaster will visit like an unwelcome guest. But it’s delicious reading. There are scenes of domestic unease and wide-scale societal breakdown, but McGregor refrains so fully from judgment that it’s never clear if the police state paranoia is madness, or a rational assessment of the situation. “If It Keeps On Raining” describes a modern-day Noah, building a tree house to escape a flood, untrustworthy – possibly insane – but impossible to dismiss. Besides, floods and rain recur throughout the collection – one can’t be too sure. One of the most inventive stories in the collection, “Supplementary Notes To The Testimony Of Appellants B & E,” give an appendix to a legal proceeding which reads like straining to hear the audio track of a horror movie from the next room.

“We Wave and Call” opens thus:

And sometimes it happens like this: a young man lying face down in the ocean, his limbs hanging loosely beneath him, a motorboat droning slowly across the bay, his body moving in long, slow ripples with each passing shallow wave, the water moving softly across his skin, muffled shouts carrying out across the water …

I wouldn’t trust anyone who thinks that boy is alive … and yet he is. McGregor embeds the shard of dread, then immediately turns to playfulness, but he makes his point: we survive by assumptions, but they also undo us. We’re never sure where the text ends and imagination begins. That’s the brilliance of any successful collection, and this one in particular: it’s all on the page. McGregor employs the alchemy between word and reader to great effect.

The collection that kept coming to mind was Dubliners, that restless unease that pulsed beneath Joyce’s epiphanic stories – people casting about for a revelation, a grand purpose, one that soon arrived in the blood-washed trenches of Europe. Even neutral Ireland felt the effects. What comes next in McGregor’s salt-blasted flatlands may be boogieman or apocalypse, but you can be sure it’s big and bad. As one character says of his friend, “Thing with Ray is he’s one of those people who can drink as much as they want without causing any problems. It’s when the drink runs out is when you want to watch him.” In this world, it’s no surprise that sobriety trumps drunkenness in misery. When Ray launches into an unhappy tale, his friend laments, “Later he told me how the story had ended. Like I’d been hanging on waiting for the final installment.” The thing is, we have.

Further Links & Resources

- Ever wonder what successful writers were doing a decade earlier? A Guardian profile of McGregor gives you a glimpse of the author as a young(er) man in 2002.

- Get a copy of This Isn’t The Sort of Thing That Happens to Someone Like You on Amazon, Indiebound, or Powell’s.