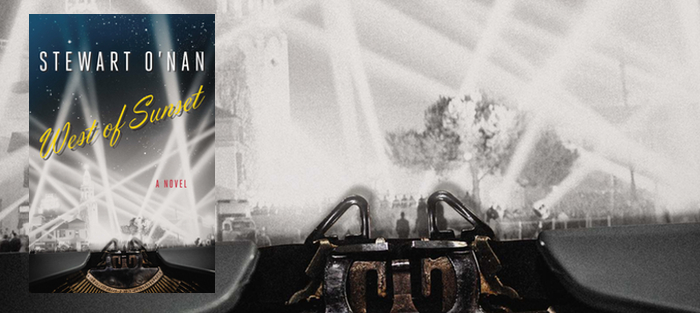

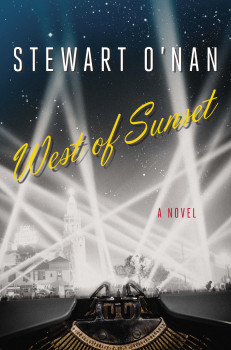

Stewart O’Nan must love the twilight—the final hours, the slow change from light to dark, those drawn-out moments just before the end. His previous subjects have included the last acts of life, of marriage, and of a Red Lobster franchise. In his newest novel, West of Sunset (Viking), O’Nan writes about the closing chapters of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s life.

In 1937, suffering from poor health and vast debt, Fitzgerald moves to Hollywood and attempts to earn a living as a screenwriter. His daughter and his wife are each in expensive institutions back east—the former at boarding school, the latter at a mental hospital. In California, Fitzgerald punches a clock at MGM, struggles with his alcoholism and other ailments, undertakes a tumultuous affair with gossip columnist Sheilah Graham, and begins his final novel: The Love of the Last Tycoon.

Many readers might struggle to imagine the author of The Great Gatsby in such a state: a washed-up writer on the low rungs of Hollywood’s ladder, financially ruined, the very opposite of the Jazz Age glamour with which Fitzgerald is associated. But it was indeed the case. Sales of Gatsby and its follow-up, Tender is the Night, never matched their critical reception. Only his debut, This Side of Paradise, sold well in the author’s lifetime, and even that put little money into his pocket. Most of Fitzgerald’s income came from selling short stories, and even in the Saturday Evening Post era, that hardly funded the extravagant lifestyle he and Zelda so briefly enjoyed.

It can be disorienting, at first, to picture such a canonical twentieth-century writer, cast under such a light, in passages from West of Sunset such as these:

“He’s actually a very famous writer,” Budd said.

“Is that right?”

“I’m not,” Scott said.

“What’s your name?”

“F. Scott Fitzgerald.”

“You’re right, you’re not.”

Someone pressed a flask on him, and they laughed as if he might be offended.

But O’Nan makes a character of Scott Fitzgerald—one that outshines the biographical whoop and holler. The star of West of Sunset is humbled by his past, well intentioned in his relationships to Zelda and his daughter Scottie, but constantly sabotaging his own efforts at redemption. Each time he looks to gain ground in his new career or new love, an alcoholic binge takes him two steps backward. At one point in the book, his lover, Sheilah Graham, describes him with these words: “He’s a selfish, angry little man who thinks he’s superior because he reads poetry and was famous once twenty years ago.” It’s a cringe-worthy cycle, and O’Nan keeps the reader always on the razor’s edge between sympathy and disgust.

The novel’s supporting cast is made up of luminaries from midcentury literature and cinema. Dorothy Parker enjoys greater screenwriting success that Scott, and enables his drinking. Humphrey Bogart proves a fair-weather friend—good for a drink and laugh, with an underlying intelligence that Scott respects. Even Hemingway makes an appearance, as Scott’s large-looming literary conscience.

But it’s the loves of Fitzgerald’s life that steal the show. Like her husband, Zelda is also in her final act. During Scott’s visits to Highland Mental Hospital in North Carolina, his wife has put on weight, found religion, and taken up painting. No longer the storied flapper of the French Riviera, prone to fits of stripping and arson, the Zelda of West of Sunset is a quieter, subtler creation—a woman tragically out of synch with the world around her. Though Scott spends much of the novel deceiving Zelda, his bond to his wife is palpable: a tether that’s as spiritual as it is legal, one he has neither the power nor the will to sever.

But it’s the loves of Fitzgerald’s life that steal the show. Like her husband, Zelda is also in her final act. During Scott’s visits to Highland Mental Hospital in North Carolina, his wife has put on weight, found religion, and taken up painting. No longer the storied flapper of the French Riviera, prone to fits of stripping and arson, the Zelda of West of Sunset is a quieter, subtler creation—a woman tragically out of synch with the world around her. Though Scott spends much of the novel deceiving Zelda, his bond to his wife is palpable: a tether that’s as spiritual as it is legal, one he has neither the power nor the will to sever.

Sheilah Graham, Scott’s current lover, experienced a Gatsby-esque rise to Hollywood prominence. After a childhood spent in London’s slums and orphanages, she worked her way up the ranks of show business and journalism. When she first meets Fitzgerald, Graham is engaged to the Marquess of Donegall. She turns her back on a royal wedding in favor of their brief affair. In some ways, Sheilah is to Scott what he is to Zelda: a cross between lover and caregiver, who knows that staying is wrong but that leaving might be worse. The manner in which Scott torments her with his drinking binges—and his profuse apologies afterwards—must echo Zelda’s manic episodes from decades past. Graham’s experience of Fitzgerald is most similar to the reader’s: always measuring the poverty of his behavior against the wealth of his mind.

Working with a concept that easily could have gone nostalgic, reverential, or just plain pretentious, O’Nan rises to the occasion. As with his previous works, he treats this subject with intimacy, grace, and a special affection for daily routines. West of Sunset is a welcome corrective for the Shakespeare-in-Love brand of writer idolatry, in which talent and will overcome all obstacles. Instead, this is the portrait of the artist as an old man, after the promise and the fame have been stripped away, and only the writing remains.

If he had failed his talent, as Ernest held, it had not been through under-use, but, rather, as he thought some mornings, his heart galloping from too much coffee, the opposite…He’d been doing it since before the Armistice, even when Zelda fell apart, and now, alone, saw no end, no respite. He was terrified he would die, pencil in hand, leaving an unfinished sentence and Scottie a legacy of debt…He was a writer—all he wanted from the world were the makings of another truer to his heart.

Like Gatsby, Fitzgerald was ultimately betrayed by the success he chased so doggedly. West of Sunset is partly a cautionary tale, partly a peek behind the scenes, but mostly a meditation on the writing life. With this book, O’Nan has broadened the legacies of two great American novelists.