As a creative writing teacher, I often hear my students compliment a story for its likable characters. Likable. It is a word I loathe, especially when it comes to literary characters, and even human ones for that matter. How about fascinating? Complex? Messy? Human. What human do any of us know who is exclusively likable? And how boring would that person be if she were?

As much as I’d love to blame this preference for likeability on my students’ naiveté, it is a comment I’ve heard from many an experienced reader—how much they loved a book because they loved the character (So funny! So nice!) or, more often, how much they hated a book because the characters were unlikeable, as if the quality of a story is determined by whether or not you want to start a knitting group or play racquetball with its characters.

In a 2013 Publisher’s Weekly interview, Claire Messud took her interviewer to task when she suggested that she wouldn’t want to be friends with the main character in Messud’s novel, The Woman Upstairs (Knopf, 2013). “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble,” replied Messud. “We read to find life, in all its possibilities.”

In a 2013 Publisher’s Weekly interview, Claire Messud took her interviewer to task when she suggested that she wouldn’t want to be friends with the main character in Messud’s novel, The Woman Upstairs (Knopf, 2013). “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble,” replied Messud. “We read to find life, in all its possibilities.”

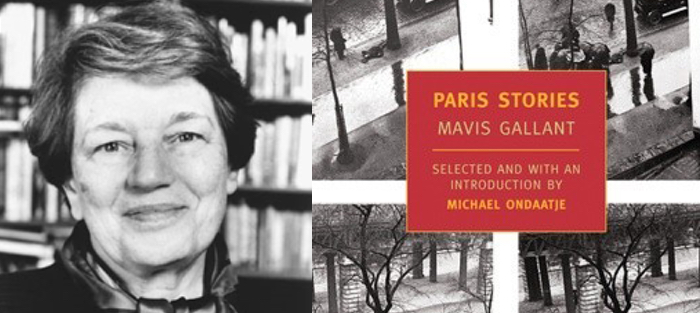

Finding life is certainly why I read, and one of the authors in whose work I find the most life is Mavis Gallant. Gallant’s stories are quietly fierce and unabashed in revealing what it truly means to be human—prejudices, foibles, inadequacies, cruelties, and all.

Gallant’s story “Mlle. Dias de Corta,” originally published in the December 28, 1992 issue of The New Yorker, serves as a high watermark for what it means to write a truly compelling, frequently unlikeable, and ultimately empathetic character. The story is told from the point of view of an unnamed elderly woman who, after seeing Alda Dias de Corta in a commercial, reflects on the time several decades ago when Alda, who was then a young, aspiring actress, rented a room from the narrator and her son, Robert. The story is epistolary in style, written directly to Alda, and begins: “You moved into my apartment during the summer of the year before abortion became legal in France; that should fix it in past time for you, dear Mlle. Dias de Corta.” If the sentence feels pointed, that’s surely its intent. We later learn that Alda had an illegal abortion when she lived with the narrator and Robert, and that the unborn child was likely Robert’s.

It strikes me as a cruel way to begin a message to someone with whom you hadn’t been in touch for decades. And indeed, the narrator is quick to one-up herself when, mere sentences later, she refers to Alda’s acting school as “provincial,” one she and Robert “had never heard of…even though [Robert] had one or two actor friends.” The narrator goes on to remind Alda of their first conversation, when she had found her new tenant, “A bit sullen, perhaps; you refused the chair I had dragged in from the dining room. Careless too. There were crumbs everywhere. You had spilled milk on the floor.” When the narrator made noise about cleaning up, she notes that Alda didn’t bother to try and help.

As if criticizing Alda’s character weren’t enough, the narrator goes on to reveal her racism and prejudice not only towards her former tenant who comes (allegedly, the narrator would have us believe) from Marseilles, but also towards the many immigrants that seem, from this woman’s perspective, to be taking over Paris like an outbreak of bed bugs. At one point the narrator says Robert told her of “a secret report, compiled by experts, which the mayor has had on his desk for eighteen months. According to this report, by the year 2025 Asians will have taken over a third of Paris, Arabs and Africans three-quarters, and unskilled European immigrants two-fifths.” The math in this statement is hilarious, but the fear and accusation inherent in it is discomfortingly familiar to anyone who has tuned in to recent conservative reportage on immigration in our own country.

But to think this a story that mocks a certain generation, demographic, and political opinion would be a gross error. Though the narrator does not stop with her barbs at her subject (she reminds Alda of all of her inadequacies—her poverty, her thinness, her quick temper and incorrect pronunciation of the French “o”), it is through her revelations about Alda that she begins to reveal her own vulnerability and regret. She reminds Alda that it was she who first noticed the girl’s “condition” when she was tailoring one of her dresses for Alda to wear to an interview. “I had finished basting the dress seams,” she says, “and was down on my knees, pinning the hem, when I suddenly put my hand flat on the front of the skirt and said, ‘How far along are you?’” There is something about this moment—the narrator down on her knees—that is harrowing and surprisingly tender. Gallant digs deeper into the psychology of this character and we find ourselves as readers moving closer toward her, our own judgment and prejudice eroding with the revelation that she is much more than we’ve been led to believe.

But to think this a story that mocks a certain generation, demographic, and political opinion would be a gross error. Though the narrator does not stop with her barbs at her subject (she reminds Alda of all of her inadequacies—her poverty, her thinness, her quick temper and incorrect pronunciation of the French “o”), it is through her revelations about Alda that she begins to reveal her own vulnerability and regret. She reminds Alda that it was she who first noticed the girl’s “condition” when she was tailoring one of her dresses for Alda to wear to an interview. “I had finished basting the dress seams,” she says, “and was down on my knees, pinning the hem, when I suddenly put my hand flat on the front of the skirt and said, ‘How far along are you?’” There is something about this moment—the narrator down on her knees—that is harrowing and surprisingly tender. Gallant digs deeper into the psychology of this character and we find ourselves as readers moving closer toward her, our own judgment and prejudice eroding with the revelation that she is much more than we’ve been led to believe.

Later, when she recalls her late husband’s struggles with the restaurant they once owned, the narrator wonders about his insistence that she never work there:

He did not wish to have his only child do his homework in some dim corner between the bar and the kitchen door. But I could have been behind the bar, with Robert doing homework where I could keep an eye on him (instead of in his room with the door locked). I might have learned to handle cash and checks and work out tips in new francs and I might have noticed trouble coming, and taken steps.

The narrator isn’t just talking about thwarting a family misfortune. Cast against the backdrop of a changing France and Alda’s illegal abortion (not to mention the legalization of it the following year), the narrator is also talking about the difference between the old and the new, the limited options on offer for her when she was young and those that were on offer for Alda. In this way Gallant speaks to a larger point about the choices women may or may not have, choices for women who are mothers and women who are not.

Near the end of the story, the narrator returns to her convoluted mathematics, calculating the amount of money Alda owes her, factoring for inflation and changes to the currency. But after going meticulously over the numbers she says, “Actually, I don’t want interest. To tell the truth, I don’t want anything but the pleasure of seeing you and hearing from your own lips what you are proud of and what you regret.”

The first time I read this line a sob escaped my throat. The narrator is talking to Alda but she is talking about herself. Gallant isn’t interested in stereotypes but what it means to be richly, deeply, imperfectly human. I feel that I know this narrator, that she is a relation of mine, some great aunt, one who infuriates and enrages me, provides comfort and commonsense; one who can be ruthless and tender, cruel and kind, one I dislike and yet, oddly enough, love. She is lonely; she invites Alda to visit her. We feel pity and maybe a little bit of shame at having been as judgmental as the narrator herself. Who are we really, to think we understand all that it means to be inside the skin of another person?

There are to me, no more perfect concluding words to a story than Gallant’s “Mlle. Dias de Corta,” capturing the pain inherent as we come close to the end of life, and the hope that lingers nonetheless. “I prefer to live in the expectation of hearing the elevator stop at my floor,” says the narrator to Alda, to us, “and then your ring, and of having you tell me you have come home.”