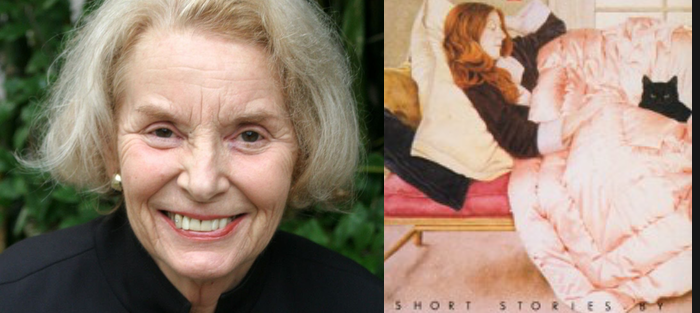

Why is “Revenge” so gleeful, so wicked, so charming?

It’s 1943 in the Mississippi Delta. Rhoda’s older brother Dudley and their cousins have built a broad-jump  pit in the pasture, where every day they practice for the Olympics. They won’t let Rhoda play, and she has a series of tantrums until her older cousin Lauralee comes home for a quickie war wedding and asks Rhoda to be her maid of honor. After the wedding, Rhoda gets into the Crème de Menthe and sneaks away from the reception, leaves her fancy new dress in a pile, and finally gets to try her hand at pole-vaulting.

pit in the pasture, where every day they practice for the Olympics. They won’t let Rhoda play, and she has a series of tantrums until her older cousin Lauralee comes home for a quickie war wedding and asks Rhoda to be her maid of honor. After the wedding, Rhoda gets into the Crème de Menthe and sneaks away from the reception, leaves her fancy new dress in a pile, and finally gets to try her hand at pole-vaulting.

Raised on Southern manners, I thrill at the way Gilchrist foxtrots through tea-sipping customs while exposing all manner of prejudice through her narrator, ten-year-old Rhoda, who absorbs the language of the adults around her and then spits it back at them indiscriminately. They are, of course, horrified at her mouth. “It’s the movies,” her grandmother says. “They let her watch whatever she likes.” Mm-hmm.

On one hand, it’s a funny story about a sassy little kid. On the other, “Revenge” plunges us into both childhood’s jealous rages and the American South during World War II. We start out safely on Rhoda’s side—they won’t let her play! And then:

“Get out of here, Ratface,” Philip yelled at me. “You German Spy.” He was referring to the initials on my Girl Scout uniform.

“You goddamn niggers,” I yelled …”You Japs, you Jews.” I was throwing dirt on everyone now. Dudley grabbed the shovel and wrestled me to the ground.

This is not the cute story that newcomers to Gilchrist might have expected. Rhoda’s family continually refers to her as their “dear sweet little girl,” which she most certainly isn’t. Such is etiquette—like a foul smell, the only way to deal with Rhoda’s improprieties is to pretend they do not exist. But Gilchrist refuses to retouch Rhoda’s perspective, anywhere, and that’s what is so astounding to me about this story.

I remember, with guilty clarity, when a boy named Garret insulted me (lamely, routinely) in sixth-grade science class, and I told him to go to hell. I’d never said it before, and when I saw his face crumple, I was startled at my own power. I went on to say much worse things, which I would not say here and can’t recount to anyone without terrible embarrassment, my hands over my face. Isn’t this true for all of us? As a writer, I’ve tried and failed to do what Gilchrist does in “Revenge.” Once, someone even walked out of a reading because of something a child in my story said! But Gilchrist sticks her landing—a grown woman recounts a summer from her foul-tempered childhood, and there was a war on, and she will not interfere in her own memory:

I began to pray the Japs would win the war, would come marching into Issaquena County and take them prisoners, starving and torturing them… I saw myself in the Japanese Colonel’s office, turning them in, writing their names down, myself being treated like an honored guest, drinking tea from tiny blue cups like the ones the Chinaman had in his store.

They would be outside, tied up with wire. There would be Dudley, begging for mercy. What good to him now his loyal gang, his photographic memory, his trick magnet dogs, his perfect pitch, his camp shorts, his baby brownie camera.

I prayed they would get polio would be consigned forever to iron lungs. I put myself to sleep at night imagining their labored breathing, their five little wheelchairs lined up by the store as I drove by in my father’s Packard, my arm around the jacket of his blue uniform, on my way to Hollywood for my screen test.

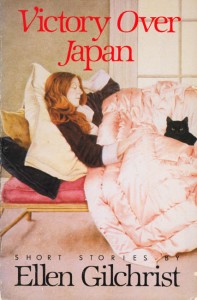

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on Ellen Gilchrist and her work, please visit Ole Miss’s Mississippi Writers Page.