“My mother was a den mother, but she wasn’t fanatical about it.” I have read that opening line of Tom Perrotta’s simultaneously hilarious and heartrending short story “The Wiener Man” several times in the past decade or so. Over the years, that deceptively simple line and the story that follows have grown more complex to me.

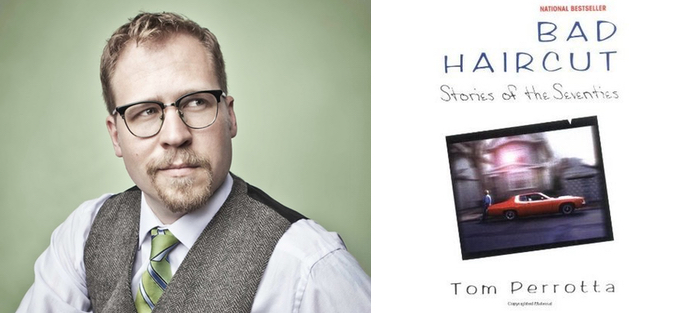

“The Wiener Man” is the first story in Perrotta’s debut book, Bad Haircut: Stories of the Seventies (Bridge Works Publishing, 1994). The collection follows young Buddy chronologically through his 1970s New Jersey boyhood in stories such as “The Wiener Man” and “Thirteen,” on through his adolescence with “You Start to Live,” and on to young adulthood in the final story, “Wild Kingdom,” which is set the summer after Buddy’s freshman year of college.

“The Wiener Man” is the first story in Perrotta’s debut book, Bad Haircut: Stories of the Seventies (Bridge Works Publishing, 1994). The collection follows young Buddy chronologically through his 1970s New Jersey boyhood in stories such as “The Wiener Man” and “Thirteen,” on through his adolescence with “You Start to Live,” and on to young adulthood in the final story, “Wild Kingdom,” which is set the summer after Buddy’s freshman year of college.

Perrotta has a pitch-perfect touch when it comes to capturing the naïve, yearning tone of youth. In “The Wiener Man,” Buddy is believably thrilled about his Boy Scout troop taking a field trip to meet The Wiener Man, a mascot in an oversized hot dog outfit who makes live appearance at grocery stores in his Frankmobile to pass out free samples of his Wonderful Wieners.

Perrotta fills Buddy with an earnestness that is funny in the moment, then heartbreaking in hindsight:

“I knew from experience that if you wanted to have a conversation with a celebrity, you had to get the ball rolling yourself. I made a mental list of the possibilities: How did you get your job? Who do you like better—Joe Frazier or Muhammad Ali? Do you own a motorcycle? What’s your favorite TV show? Were you ever in the service, and if so, what was your rank? Have you traveled to foreign countries? Do you know Chef Boy-R-Dee?”

It doesn’t take long for the cracks to show:

“The Frankmobile was parked in the far corner of the lot, where Stop & Shop met Ye Olde Liquor Store. My heart sank when I saw it. I had taken the name seriously and expected to see a huge hot dog on wheels. But it was just a pink Winnebago.”

Ever the optimist, Buddy keeps his chin up and clutches his autograph book in sweet anticipation of meeting the Wiener Man. He jokes with the other Boy Scouts and solemnly mulls his social standing amongst the troop. The story maintains a sense of bright-eyed innocence even as the Wiener Man confronts a gang of older kids smoking to the side of his hot dog giveaway. Things begin to shift when Buddy’s mother recognizes the Wiener Man as Mike Amalfi, an old friend from high school.

Eventually, Buddy and his mother are invited inside the Frankmobile. Mike has stripped off his foam hotdog outfit and wiped his face clean of pink make-up. The three are wedged together in the cluttered pink Winnebago and the sad reality of Mike’s life as the Wiener Man is laid bare: his father has died of cancer, his mother is alive but a pain in the ass, he never married. When Mike confesses to being lonely, Buddy’s mother tells him he is still young and should marry, to which he replies: “It don’t feel so young.”

The scene is fraught with adult problems threatening to intrude on Buddy’s innocent afternoon, yet Buddy busies himself with a handheld game called Hi-Q and only catches snatches of the conversation: “I didn’t get the joke, but I laughed anyway. I was really enjoying myself. I liked the coziness and dim light inside the Frankmobile.”

Buddy seems oblivious. And isn’t that true?

I don’t mean that in a condescending or judgmental way, simply as an honest observation that we are so blissfully oblivious until we, well, suddenly aren’t.

As the scene inside the Frankmobile plays out, Buddy’s mother is endlessly tender with Mike, gently trying to boost his flagging confidence, and it is this scene, these moments, that I had failed to linger on in earlier readings, not read closely enough or, perhaps, was not able to read fully at a younger age. Tobias Wolff—Perrotta’s teacher at Syracuse University—has pointed out that his former student’s early stories are not only “funny,” they are “deeply touching.” For years I had focused on the funny. I had also focused on Buddy when I read this story. And, of course, “The Weiner Man” is Buddy’s story as told in his voice, but whether he realizes it or not Buddy is also telling—even if it is unintentional and sometimes a telling by withholding—his mother’s story and his parents’ story.

Eventually, Buddy’s mother sends him out of the Frankmobile on a made-up errand to buy a can of tomato sauce in the Stop & Shop. “Wait for me outside,” she says. “I’ll only be a few more minutes.” Whatever happens next inside the Frankmobile happens off the page, and for that I feel both grateful for Buddy’s sake and wistful for a time when my own life still held such blissful obliviousness.

When I was fifteen years old, my mother and stepfather divorced: one weekend my stepfather moved out to live with a woman he had been seeing, and the next weekend my mother moved into our house the boyfriend she had been sleeping with on the side. The new boyfriend drove a refrigerator truck between Maine and Boston selling seafood and, I came to suspect, other even more lucrative things. My mother regularly accompanied him on the road. The wild irregularity of the hours he kept seemed to match my mother’s wildly oscillating mood swings.

One Saturday, my mother and her boyfriend were napping in the middle of the afternoon after having made a pre-dawn seafood delivery run to Boston. I wanted to leave and meet some friends to go skateboarding, so I poked my head into my mother’s bedroom to say as much; I was scared to wake her but more scared of being grounded for not telling her I was leaving. But I didn’t wake her. Instead, I found my mother moaning and moving her hips beneath the seafood dealer, all the blankets bunched at the foot of the bed, their nakedness glowing in the strange, muted drawn-shade light of the bedroom.

In the final, hurtling movement of “The Weiner Man,” Buddy’s mother steps urgently out of the Frankmobile and the pair rush to meet Buddy’s father at the lamp store where he works unhappily as the assistant manager. Buddy’s father is at the store window and sees his wife and son coming down the sidewalk. He turns away to close up the store for the evening and Buddy observes, “When he hit the master switch, that whole galaxy of lamps went black.”

A few months after I had startled my mother and her boyfriend in her bedroom, a completely unrelated incident would lead her boyfriend to tackle me to the floor, then punch me repeatedly in the head and face. My mother took his side in the matter. My father took me from her house and sued for full custody of me. I was sixteen. My world, it seemed at the time, went black.

In an essay about the power of re-reading, the short story writer Andre Dubus once wrote, “A story can always break into pieces while it sits inside a book on a shelf; and, decades after we have read it even twenty times, it can open us up, by cut or caress, to a new truth.” This is how Tom Perrotta’s “The Weiner Man,” has worked on me over the years: a funny story that has revealed new dimensions as I have read it each time as an older, different reader.

During May of 2016, Joshua Bodwell celebrated National Short Story Month by selecting one short story each day and writing a micro-essay that attempted to contextualize how the story fit into his reading life and the lasting impact the story had made on him. He posted the essays on Facebook each day.

In the end, he wrote nearly 18,000-words about thirty-one different stories by thirty-one different authors. A version of this essay on Tom Perrotta’s “The Weiner Man” appeared as the twenty-sixth installment of that thirty-one day project.