I’ve always loved Raymond Carver’s short story “A Small, Good Thing.” Maybe not always. I hadn’t read it before I put it on my first syllabus, back when I was a grad student teaching Intro to Creative Writing at the University of Colorado, like a number of the stories on the syllabus, but I figured it was in the anthology we were teaching out of, and I was supposed to teach these kids something about writing (something that a twenty-six-year-old could have known about writing), and so how bad could it have been? I was pleasantly surprised when I finally read it in the days (oh, who am I kidding, the night) before the class I was supposed to teach it. I’m sure the discussion of content and form and style and diction and syntax and tone and characterization and dialogue and scene and summary filled the entire fifty minutes, if not a couple of class sessions. (The good stories were always making us fall behind.) But unlike a lot of the stories I taught in those blissful, boozy, high-altitude semesters, even stories I’d actually read and admired before assigning them, “A Small, Good Thing” has stuck with me ever since.

I’ve always loved Raymond Carver’s short story “A Small, Good Thing.” Maybe not always. I hadn’t read it before I put it on my first syllabus, back when I was a grad student teaching Intro to Creative Writing at the University of Colorado, like a number of the stories on the syllabus, but I figured it was in the anthology we were teaching out of, and I was supposed to teach these kids something about writing (something that a twenty-six-year-old could have known about writing), and so how bad could it have been? I was pleasantly surprised when I finally read it in the days (oh, who am I kidding, the night) before the class I was supposed to teach it. I’m sure the discussion of content and form and style and diction and syntax and tone and characterization and dialogue and scene and summary filled the entire fifty minutes, if not a couple of class sessions. (The good stories were always making us fall behind.) But unlike a lot of the stories I taught in those blissful, boozy, high-altitude semesters, even stories I’d actually read and admired before assigning them, “A Small, Good Thing” has stuck with me ever since.

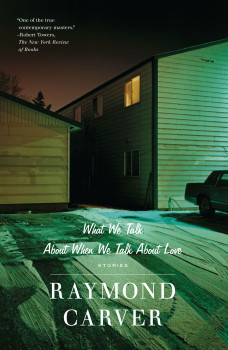

One of the reasons why is that it can be read a study in the art of editing—or perhaps a cautionary tale. Back in my Boulder days, I’d found an obscure book on craft, a book on craft I actually liked. Its thesis was that writing is really revision, which is a theory I’ve always taught and believed to be true myself. Toward the end of the book, there’s a section about writing after publication, and it uses, by way of before-and-after illustration, the story that appeared in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love called “The Bath.” “The Bath” is a much shorter version of “A Small, Good Thing.” The textbook claimed it was an early draft that Carver, ostensibly dissatisfied with its brevity (without wit), went back to, revised, and dramatically expanded prior to its (re-)publication in his next collection of fiction, Cathedral. Later, I’d find out, as the world found out, that this wasn’t exactly what happened. We know now that the original draft was not an example of Raymond Carver’s stark Hemingwayish minimalism but actually that of his overbearing editor’s. “A Small, Good Thing” had gotten Gordon Lished and then un-Lished. And we’re very lucky as readers for that. The longer story is much more of a story. The first story? I don’t know. A flash fiction of sorts. It reads well, obviously; the first collection was, and is, highly regarded. It just doesn’t sound like Carver and it doesn’t let this story get fully told. Gordon Lish, Carver’s editor at the time, an editor whose onetime nickname was Captain Fiction, did and does a lot of things well (he, after all, retitled the collection’s eponymous story “Beginners”), but writing or rewriting Carver for Carver wasn’t one of them. Anyway, even though I was unwittingly lying to the room (students from my English 1191 in 2001, 2002ish, sorry for misleading you), thanks to this textbook, there was a good lesson to be learned, albeit a counterclockwise lesson, about the successes and failures of revising, of having editors edit you too heavily (or not enough), and how if you save your drafts, you can always go back and make restorations at a future point. So, it wasn’t a total waste of time.

And like every good Carver story, there’s more to the story about the story. Six years after I finished grad school (and teaching, more or less), I got to read an even longer draft, thanks to The Library of America’s (LOA) definitive 960-page Collected Stories. This draft, also called “A Small, Good Thing,” was included in a manuscript called Beginners, which preceded WWTAWWTAL. I actually read the manuscript version and the published version side by side at one point. Of course there were the sorts of edits on the sentence level that one who writes would expect to see over the course from manuscript to story collection. But also there was a big section—a very religious big section—that somebody decided didn’t belong in the story. I’m guessing that it was probably two people who made this cut, first Lish when he bowdlerized Beginners and then Carver when he went to restore the atrocity in it that had Lish had rewritten as “The Bath.” I won’t say more about the long expurgated section, so as not to ruin the excitement of discovering it and fictive power it contains. (It was a rather exciting moment.) It’s a very haunting passage. I recommend reading the manuscript version from the LOA edition, but not in a cold, dark room at five in the morning, like I did when I first encountered it.

And like every good Carver story, there’s more to the story about the story. Six years after I finished grad school (and teaching, more or less), I got to read an even longer draft, thanks to The Library of America’s (LOA) definitive 960-page Collected Stories. This draft, also called “A Small, Good Thing,” was included in a manuscript called Beginners, which preceded WWTAWWTAL. I actually read the manuscript version and the published version side by side at one point. Of course there were the sorts of edits on the sentence level that one who writes would expect to see over the course from manuscript to story collection. But also there was a big section—a very religious big section—that somebody decided didn’t belong in the story. I’m guessing that it was probably two people who made this cut, first Lish when he bowdlerized Beginners and then Carver when he went to restore the atrocity in it that had Lish had rewritten as “The Bath.” I won’t say more about the long expurgated section, so as not to ruin the excitement of discovering it and fictive power it contains. (It was a rather exciting moment.) It’s a very haunting passage. I recommend reading the manuscript version from the LOA edition, but not in a cold, dark room at five in the morning, like I did when I first encountered it.

So, why is Carver so important beyond the obvious reasons? We’d probably need a couple of fifty-minute class periods to analyze it thoroughly. But I can say this: his stories are so honest, in a way that I feel a lot of contemporary fiction today lies to us. He wasn’t trying to be fashionable by writing blue-collar. He was the twenty-five-year-old guy who’d come to academia by way of a sawmill with two kids and a wife he hated to love and loved to hate. Carver was the guy from California sitting at the conference table in the workshop at Iowa who actually had something to say and cared enough to want to learn how best to say it.

“A Small, Good Thing,” like Carver’s later “Cathedral,” like Joyce Carol Oates’s “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?,” Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use,” and Henry James’s “Daisy Miller,” these are stories that will always feel like the epitome of story to me. There aren’t many more. I don’t add to this pantheon often. That kind of fiction simply doesn’t happen a lot for me anymore. So many stories I come across may bang around in my head—at best—for a few minutes after I’ve finished them. But I can sit here and recall “A Small Good Thing” in such detail—emotional detail—without even a glance at the text. That’s a well-told story, I’d say. The ones that can have that kind of effect on you, both as writer and as reader, these the paragons of fiction to which we all (should) aspire.