I was amused when Fiction Writers Review asked if they could post this piece on reviewing poetry after the criticism panel at AWP. I thought perhaps they might be asking me to map out the territories of irrelevance that are awaiting even those who review fiction, given the rapidly changing world of literary publishing. After all, outside the literary journals catering almost exclusively to the initiated—an exclusivity that demands a previously acquired expertise or at least an attitude (and that is even more evident in the blogs)—poetry seems to be reviewed less and less. I’ll admit that my evidence for this is what my scientific friends call “anecdotal,” but it seems obvious to me that there is much less attention to poetry than there was even five years ago. The poetry reviewer can still get the occasional assignment to review a new biography of one of the great dead, or perhaps do a profile of a Poet Laureate or Pulitzer winner, particularly if there is something weird about them—and, thank God, there does seem to remain something just a little weird in anyone who devotes his or her life to poetry. We might even get to write about a poet—probably a young poet—who has a dynamic stage presence. But the chance to review a new collection of poems in a place where several thousand people might read it, and to actually be paid something for our labors, has almost disappeared. In the fairly recent past many people still considered a knowledge of the poetry of the moment—even if that knowledge came only from reviews or the occasional poem appearing in a high brow magazine–as an essential element of the life of the mind, or at least as an important ingredient of contemporary culture. If there ever was a consensus about that, it has been forgotten.

There are probably many reasons for this lack of attention in the larger cultural life, but it must surely have something to do with a perfect storm combining technological change, the change in educational curricula necessitated by that technology, and the difficulties of the postmodern idiom in much of our poetry, an idiom that is also probably necessary. I should say that I am not particularly disturbed by this. When people ask me if I think poetry is dying because of the new technologies, my response is—Our art survived even the invention of writing! Next to that the invention of the computer seems like a small variation.

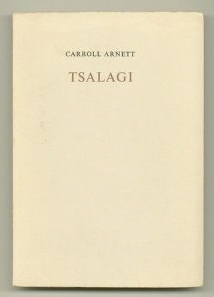

The future and purpose of the poetry review, however, has changed, or perhaps has accepted its most narrow definition. When I was just beginning to publish my poetry in small regional journals in the mid 1970s, it seemed an obvious extension of that process to write the occasional review. I was trying to learn things, trying to figure things out about the art, and organizing my thoughts in a review helped me do that. I had just returned to the United States after several years in Europe, and was reading the work of ethnically identified writers with a new interest. The first review I did in 1976 was of a small press book by the Native American poet, Carroll Arnett. I sent it off unsolicited to Joseph Bruchac at The Greenfield Review, and he accepted it almost immediately. I even got paid for it. I was shocked. I could present an opinion—hopefully considered, although still quite tentative—of a small book most people hadn’t heard of, nor were ever likely to see—and that opinion would be rewarded. About the same time I was trying to figure out what so many poets of the generation before mine were trying to do with their plain spoken poetry. I’d just spent years reading French poetry, and this American thing was very different. I wrote a review of a book of interviews and essays by David Ignatow—a poet who deserves to brought back into the conversation—and sent it off to New Letters, edited in those days by David Ray. Once again, it was accepted immediately, and I received a check for $5. Not long after, I thought I might try to do more with this thing and approached a newspaper—it might have been The St. Louis Post Dispatch—and actually received an assignment. I had those tear sheets from the two literary journals to show the editor there so he took me seriously. I might have been paid $25 for that review. Oh, brave new world that has such money in it! I went for a decade, maybe two, where I was able to get recognizable checks from places like The Detroit Free Press, The Chicago Tribune and The Los Angeles Times, among others. The reviews I wrote for those places were not usually of poetry, but could occasionally get one in, and the discussion of the art was always taken very seriously.

The future and purpose of the poetry review, however, has changed, or perhaps has accepted its most narrow definition. When I was just beginning to publish my poetry in small regional journals in the mid 1970s, it seemed an obvious extension of that process to write the occasional review. I was trying to learn things, trying to figure things out about the art, and organizing my thoughts in a review helped me do that. I had just returned to the United States after several years in Europe, and was reading the work of ethnically identified writers with a new interest. The first review I did in 1976 was of a small press book by the Native American poet, Carroll Arnett. I sent it off unsolicited to Joseph Bruchac at The Greenfield Review, and he accepted it almost immediately. I even got paid for it. I was shocked. I could present an opinion—hopefully considered, although still quite tentative—of a small book most people hadn’t heard of, nor were ever likely to see—and that opinion would be rewarded. About the same time I was trying to figure out what so many poets of the generation before mine were trying to do with their plain spoken poetry. I’d just spent years reading French poetry, and this American thing was very different. I wrote a review of a book of interviews and essays by David Ignatow—a poet who deserves to brought back into the conversation—and sent it off to New Letters, edited in those days by David Ray. Once again, it was accepted immediately, and I received a check for $5. Not long after, I thought I might try to do more with this thing and approached a newspaper—it might have been The St. Louis Post Dispatch—and actually received an assignment. I had those tear sheets from the two literary journals to show the editor there so he took me seriously. I might have been paid $25 for that review. Oh, brave new world that has such money in it! I went for a decade, maybe two, where I was able to get recognizable checks from places like The Detroit Free Press, The Chicago Tribune and The Los Angeles Times, among others. The reviews I wrote for those places were not usually of poetry, but could occasionally get one in, and the discussion of the art was always taken very seriously.

Once I had proved myself in this way, I started getting more chances—including the opportunity to do the longer review/essay that continues to be in the better literary journals. I wasn’t so much interested in the serial review—one reviewer doing several new books one after the other (the kind of review that Poetry does so well)—but wanted to find patterns in the books given to me for discussion, some way of relating the books and their authors to a larger question. Those questions were usually the ones worrying me in the making of my own poetry. Some readers might have thought I was shoe-horning books into some preordained rubric, but I was deeply motivated to do those pieces. I wrote them for places like The Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Poetry Ireland. More recently, The Boston Review has given me room occasionally to expand at some length about single authors and their books. What I’ve noticed over the years, is that when I write for these places I assume the audience knows and cares about the nuances of contemporary poetics. I may have to do an explanation of the way Carl Phillips, for example, uses association in some of his poems and the way someone else, maybe Michael Collier, avoids it, but I expect the audience to have some knowledge, even to take sides. And I absolutely know that audience to be a very small one, each member initiated to some degree.

preordained rubric, but I was deeply motivated to do those pieces. I wrote them for places like The Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, and Poetry Ireland. More recently, The Boston Review has given me room occasionally to expand at some length about single authors and their books. What I’ve noticed over the years, is that when I write for these places I assume the audience knows and cares about the nuances of contemporary poetics. I may have to do an explanation of the way Carl Phillips, for example, uses association in some of his poems and the way someone else, maybe Michael Collier, avoids it, but I expect the audience to have some knowledge, even to take sides. And I absolutely know that audience to be a very small one, each member initiated to some degree.

I wish I didn’t feel that. I wish I were speaking to a much larger audience. I wish I were hooking some new fish for the art to feed on. But I know I’m not. When the internet became a place to find both reviews and blogs about poetry, I was hoping that there would be a more expansive tone to the discussion of contemporary poetry. Instead, I found just the opposite. The sense of speaking to the club is even more pronounced in almost all the internet discussion of poetry. The sense of the different clubs is even more pronounced than it is in the literary journals. Now I love all that discussion, of course. I’ve tried my hand at blogging (for the Michigan Quarterly website, and for Dan Wickett’s site associated with Dzanc Books), although I still feel very wooden at it. I’ve reviewed a couple of times online—and was even wonderfully edited by Matt Bell at The Collagist.com—much more severely and judiciously edited than I have been the last couple of times I’ve written for a major newspaper. The paper just doesn’t have the staff for it anymore, but Matt Bell is a smart and indefatigable young writer. But I haven’t been paid for this online work—and I’ll admit that does change my attitude toward the work.

By and large the poetry blogs—my own first attempts at it, included—have that casualness, that sense of immediacy, that the medium is famous for. Even though those words seem to never disappear, they are available only if you make a particular effort to find them. They seem casual, throw away, light weight. They can be fun, but they don’t seem to be creating the critical context by which a culture understands poetry—the old model that put the reviewer in the forefront of serious criticism.

That said, something like Ron Silliman’s blog, among a few others I read, has become absolutely essential. Now most of us who would go to Silliman’s site, know that here is a blogger and poet with a definite attitude. He is after all, one of the founders of LANGUAGE Poetry. Yet, the blog is wide-ranging and generous even as it can be quite direct in its criticisms.

But what of the future of reviewing poetry? The growth of the writing programs has assured a steady stream of initiated readers. Small presses continue to do small books of poetry—and I’m guessing that will continue, even if done only out of some marginal and antiquarian motivation. We will continue to find ways to present and value “books” online. Initiated readers will want to find out about all that poetry—although I suspect suspicions about the reviewer’s motivations will continue, even grow. This is not new—the author of that first book I reviewed, Carroll Arnett, was a teacher of mine. I gave the book a very good review.

I wonder if young poets will still think reviewing is an essential part of the process of making poems. I don’t know. These new ways of discussing the art might make that question completely unnecessary. I fear, however, that that will be a loss, even if only a temporary one, a diminution of attentive reading and yet another victory for the various literary fashions that seem to be continually swirling across the surface of the art.

Editor’s Note:

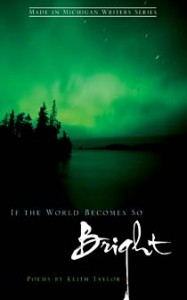

It is our great pleasure to publish this essay by special guest Keith Taylor. Taylor coordinates the undergraduate program in creative writing at the University of Michigan and directs the Bear River Writer’s Conference. He has published eleven volumes: collections of poetry and short fiction, edited volumes, and translations. His work has appeared in such publications as Story, The Los Angeles Times, Alternative Press, The Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Notre Dame Review, The Iowa Review, Witness, Chicago Tribune, and Hanging Loose. His most recent book, If the World Becomes So Bright, was published in 2009 by Wayne State University Press. His next collection of poems, Marginalia for a Natural History, will be published by Black Lawrence Press in 2011. Ghost Writers, a collection of ghost stories co-edited with Laura Kasischke, will also be published in 2011 by Wayne State University Press.

It is our great pleasure to publish this essay by special guest Keith Taylor. Taylor coordinates the undergraduate program in creative writing at the University of Michigan and directs the Bear River Writer’s Conference. He has published eleven volumes: collections of poetry and short fiction, edited volumes, and translations. His work has appeared in such publications as Story, The Los Angeles Times, Alternative Press, The Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Notre Dame Review, The Iowa Review, Witness, Chicago Tribune, and Hanging Loose. His most recent book, If the World Becomes So Bright, was published in 2009 by Wayne State University Press. His next collection of poems, Marginalia for a Natural History, will be published by Black Lawrence Press in 2011. Ghost Writers, a collection of ghost stories co-edited with Laura Kasischke, will also be published in 2011 by Wayne State University Press.

An earlier version of “Some Thoughts on Reviewing Poetry in 2011” was delivered as part of the 2011 AWP panel “The Good Review: Criticism in the Age of Book Blogs and Amazon.com,” moderated by Jeremiah Chamberlin. Joining Taylor were Charles Baxter, Stacey D’Erasmo, and Gemma Sieff. The goal of the panel was to examine how criticism is changing in a literary landscape increasingly dominated by new media, as well as to discuss how books get reviewed and by whom, why vigorous reviewing is necessary, and ways to write reviews that matter. It was a vigorous discussion, both during the talks and after. And so in the spirit of continuing that conversation, as well as bringing it to those who weren’t able to attend the panel, Fiction Writers Review has been publishing these talks by the panelists throughout this week. Here are the previous ones:

Further Links:

- On Tuesday we published “The Good Review,” by Jeremiah Chamberlin.

- On Wednesday we published “Owl Criticism,” by Charles Baxter.

- On Thursday we published “An Education in Book Reviews,” by Stacey D’Erasmo.