Books will die. They must. They’ll die like languages die. Like cultures die.

Nobody knows this better than the U.S. Office of Nuclear Waste Management, who in 1984 hired linguist Thomas Sebeok to figure out a way to warn future generations—we’re talking thousands of years into the future—that nuclear waste is buried in the vicinity, and to take heed.  Sebeok concluded that the waste, to be buried deep beneath the Yucca Mountains in Nevada, could never be warned with language. Radioactivity will last 10,000+ years—there is no permanent tongue, written or verbal, that will retain its meaning over that length of time. Words are too abstract, too based on contemporary knowledge. Electrical systems were ruled out—they need power—as were ideograms—they are as abstract as words. Sebeok’s answer was the formation of an “Atomic Priesthood,” a folkloric relay system by which knowledge could be passed on, generation to generation, in whatever language ruled the day.

Sebeok concluded that the waste, to be buried deep beneath the Yucca Mountains in Nevada, could never be warned with language. Radioactivity will last 10,000+ years—there is no permanent tongue, written or verbal, that will retain its meaning over that length of time. Words are too abstract, too based on contemporary knowledge. Electrical systems were ruled out—they need power—as were ideograms—they are as abstract as words. Sebeok’s answer was the formation of an “Atomic Priesthood,” a folkloric relay system by which knowledge could be passed on, generation to generation, in whatever language ruled the day.

We know from religion and the Bible that this type of telephone game can lead to differences in meaning and interpretation, but the lesson here still applies: language and the books they compose may die, but storytelling never will. Like song and dance, stories are eternal to how we humans communicate and express ourselves. People will always write because they will always have something to say. Or teach. Or discover. For a long time, this has been accomplished with bound books, with paper and ink. And for a long time, it will continue to be.

The book is going nowhere.

Allow me to repeat that: the book is going nowhere.

bookbinding / photo by Nate Steiner

Electronic readers need a massive install-base spike simply to step on the printed-word’s playing field; just look at Reader’s Digest, whose 9,000 digital subscribers comprise a mere .16% of its 5.5 million print readership.

Unfortunately, going nowhere applies not only to the printed book’s short-term security, but also its long-term plans for product innovation. As Richard Howorth, owner of famed Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, recently told Poets & Writers magazine, “Digital technology will go on, on its own path, no matter what. But in terms of books, I maintain that a book is like a sailboat or a bicycle, in that it’s a perfect invention.”

True. But not everyone wants to be a sailor or to ride a bike. At least not all the time. So should we scold wind surfers and wake boarders for not wanting to steer a rudder or hoist a sail? Or tell motorcycle enthusiasts and Vespa owners to give up their rides in favor of 10-speeds? Yes, we might end up with fewer skippers and cyclists in the long run, but these new sports have no more led to the demise of their predecessors than e-readers will destroy the book.

image by ramblinworker

Why? Because e-publishing isn’t a replacement for classic print, it’s a new offering; less an evolution than the birth of an entirely new species. Mobile, on-demand, and increasingly interactive, storytelling in today’s electronic-age may well end up looking Jurassic compared to the ways many of us devour narratives hundreds of years from now—it may appear damn well folkloric. But this essay’s e-age will be remembered; littered with the fossils of failed e-readers and fiction experiments, it shall live on, a layer of sediment for future storytellers curious when narrative took that binary flip from the 0 of print to the 1 of touchscreen.

Forget e-books—they are a question of format, not content. These devices, similar to online literary journals like this one, are simply the first primordial steps in a specialization that will change how the written word tells stories for future generations. As the capabilities of electronic narrative expand and specialize, they guarantee that e-books available today will look nothing like the e-stories of tomorrow; not so much the broadside becoming newspaper as the comic strip becoming Pixar, a literary leap in scope and function that won’t just create new forms and audiences, but complement our classic ones.

In the same way that the modern art movement called into question what it meant to call something “art,” this will be an era that both challenges our static definition of “writing” and redefines the relationship between “writer” and “reader.” It will change who publishes, how they publish, and what form they publish in. Today’s technological delights are well on their way to becoming tomorrow’s demands, entrenching themselves in ways that will do more than force bookbinding as a business model to adapt, but allow writing, as an art form, to expand and thrive. These are good things.

Welcome to the age of Binary Bookmaking.

photo by RyAwesome

Even with the speed, safety, convenience and affordability of microwave ovens, people still use and love their gas ovens. Foods just taste better from a real oven—they are less soggy, more textured. Like the microwave oven, the rise of the e-reader provides audiences with speed and convenience and, in the long run, affordability. Of course there will still be the folks who prefer the taste, the experience, of old-fashioned paper and ink; and for them, the industry will live on, albeit in a slightly smaller form. But these will be increasingly older folks, and several generations from now, they’ll be all but replaced by generations as intimate with computers as crayons.

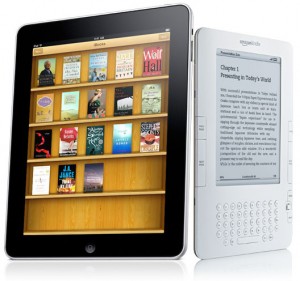

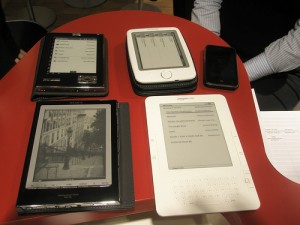

Today we have some intriguing early players vying to lead that charge. Some, like Barnes and Noble’s Nook, are cannibalizing their own bricks-and-mortar stores. Others, like Amazon’s Kindle, are operating at a loss in hopes of future market dominance. The latest, Apple’s iPad, looks to revolutionize book selling with iBooks like it did music with iTunes, offering publishers a new magnitude of interactivity with which to connect audience to content. With the exception of the iPad, these e-readers and their pixilated pages are simply new ways of consuming an old form. Content convergence like this comes when technology fuels convenience, a cycle as inevitable as the seasons, and worth our attention for just as fleeting a moment, for what lies ahead is far less about format than content—less baking or microwaving than molecular gastronomy.

Kindle vs. iPad / photo from http://www.engadget.com/

These initial e-book entrants vie for our eyes, boasting their own batch of competitive advantages, but how they will affect the health of reader-nation is less important than how they will completely repopulate it.

For those wondering whether electronic reading will truly add new readers or simply fracture existing ones into multiple distribution channels, your answer is: it doesn’t matter. For those curious if people will read more when their readers are not merely books but supercomputers capable of messaging, surfing, and gaming, your answer is: it doesn’t matter. The e-reader movement is less remarkable for its advances in technology than how that technology will create new needs, new sustenance. After plopping down a considerable introductory cost for a peek at the future, these consumers will be hungry for what represents it. Concerns over fracturing and cannibalization give little pause when weighed against the long-term significance of this, the birth of a new species of reader.

The publisher that embraces the differences between print and electronic reading for what they are—opportunities to break form, innovate and market more effectively—will be at the forefront of a new generation of readers who have happily replaced “active” reading with “shared” reading. The rise of social media has conditioned these young audiences into transparency. Today’s readers share their consumptions online via Twitter, Facebook, and Google Buzz. All this has resulted in the migration of dialogue; conversations that once dominated water-coolers and book clubs still take place, but on billions of wi-fi enabled soapboxes, and these conversations are themselves sharable. Specific to the literary arena, issues are openly debated on sites like HTMLGiant, while at Fictionaut, an entire writing community has been built to share, critique and support one another’s work. The act in active reading will continue to become the act of sharing, and this holds tremendous promise for how reading and writing will evolve on e-reader devices.

E-reader technology allows the original tent-poles of active reading to continue their migration into the social-networking space; rather than annotate and underline a book’s text for oneself, rather than pass it on to a friend or sibling, saying, “You’ve got to read this,” tomorrow’s active readers will annotate and underline properties by sharing the author’s words along with their own responses online. These readers will do so not just to select folks installed into their network, but their entire network—hundreds of people that swell into thousands on wildfires of sharing. The clouds above us have long been stared at amidst moments of reflection, for illumination of meaning; tomorrow, the cloud will help store and share these things. Active readers’ reactions and interpretations will be shared publicly and willingly so; not just great quotations or moving passages, but critiques and questions. Imagine a book club of, well, infinite size. For it contains not just members, but any Internet pedestrian scrolling by. These browsing passersby already stumble across more content and opinions than ever before, and through this process refine their preferences and expand their experiences. This same benefit will apply to e-reader audiences. This new species of reader will be exposed to more literary content than ever before—not in place of sustained reading but rather in addition to it.

a book club discussing *The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao* / photo by Paul Lowry

Again, these are good things. The question to this essayist is less how publishers can keep bound-book reading relevant or reading itself relevant than how one capitalizes on the way today’s readers read and tomorrow’s readers share—how do we use these e-reader technologies to our advantage, not simply as stewards of the written word but storytellers in search of audience? And, most importantly, how will it make us better writers? How will it challenge our notion of form, of structure, of content? How will it create a more symbiotic relationship between teller and told, between vision and envisioner?

Similarly, e-reading should be seen less as competition than opportunity; not the microwave replacing its gas patriarch but a whole new kind of fire. E-lit can take what today’s audiences do best and tailor its storytelling to let them do just that: to share and boast, to nibble nimbly. To do so, Binary Bookmaking will require a new kind of author writing a new kind of story that will ultimately demand a new kind of publishing. The variables in this formula will grow and fluctuate as the technologies that govern them do. From here forth, authors will not just work to engage their readers but engage the devices that deliver them.

Empire Theatre, Sydney 1927 / photo by Sam Hood, from State Library of New South Wales on Flickr

Binary Bookmaking can be difficult to conceptualize because we already know what books are. We grew up holding them, dream of writing them. This makes conceptualizing what e-“books” might look like in the future such a polarizing act. We have no problems with books in their current form—they’ve done us absolutely no wrong. Calling this new form an e-anything, let alone an e-“book” feels downright treasonous; not only are we beheading our benevolent queen, we are giving her successor the same name plus prefix. The e-book can’t be called an e-book because it won’t end up looking or reading or smelling anything like a book-book. The book: covers binding pages slathered in ink, a printed permanence. The e-book: a backlit screen pretending to be whatever it is you’ve clicked, a digital shape-shifter.

While today’s e-books are predominantly translations into digital code, tomorrow’s might as well be written in a whole new language. Though, frankly, this isn’t particularly revolutionary. At the turn of the twentieth century, Modernist authors such as Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Ford Maddox Ford, and Malcolm Lowry re-fashioned and manipulated language to re-vision what writing could be. How stories were told. How the lived life felt. These writers came of age in a changed and increasingly technological world, one whose influence we can see in the fragmentary and multi-perspective nature of their work. Sound familiar?

Similarly, the inner-reading of literature will branch into social-reading. The work readers do to visualize and imagine will be augmented—if not outright replaced—by embedded videos, infographics, maps, and more. At this point, e-books won’t be books because we won’t just be reading them. We’ll be reading but we’ll also be watching, touching, exploring, choosing, micro-transacting, listening, dragging, playing. So much of the internal work a paper-and-ink novel demands from its reader will no longer be necessary, but in its place, wholly new kinds of work will be born. This doesn’t replace reading so much as invite in a new type of reader. Doesn’t replace writing so much as provide authors with a new outlet and form. It’s not a revolution in language so much as a new type of communication—one predicated on how the audience encounters (and, now, participates in) the artist’s vision of the world. So what the hell do you call something like this? Besides, of course, monumental?

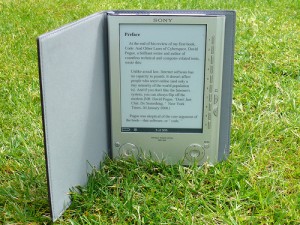

photo by sidewalk flying

photo by goXunuReviews

For all the connections one might make with products that have replaced their predecessors in the past—the automobile and horseless carriage—forms of art are different: they deal in audience, not consumers; depth of thought, not convenience of hand. Though motion pictures originated as filmed theatre, the two forms co-exist today, which is precisely why the question of book and e-book always comes back to audience. Though many folks will stick to the book and its pages, to the shared intimacy that comes with reading another’s words and bridging the gap with one’s own imagination in a sustained and immersive way, this fact has as much to do with taste as it does upbringing. These are the same folks who grew up using bound encyclopedias in schools, not online computer-labs. Atlases and phonebooks, not Google Earth and Facebook. Like their audience, the artists raised in this digital period will craft content in line with their own tastes and expectations and experiences: while the book is indeed going nowhere, electronic storytelling will gradually become storytelling driven by words, not dictated by them.

The specialization of this future “other” e-book will add new kinds of work at the price of old kinds of joy. The isolated experience fundamental to author and reader, that incredible sensation that a novel was written for you, its author speaking directly to you, will not exist for readers of the e-page. No matter how badly savvy publishers will try to keep the sensation on life-support behind veiled preference settings, the social conversations that occur below or within future e-book texts will become another pleasure of reading, complimentary to the splendor of entering a world by oneself. This shouldn’t alarm because print isn’t going away.

photo by oddsock

That splendor won’t wither and withdraw into some kind of non-digital dormancy, a passé sensation appreciated by the literary faithful—it will continue to exist, not waiting to be rediscovered by a future generation of hipsters who dust it off like leg warmers and flannels and start blogging about how awesome “ real” books are, but, like theatre and film, beside print, in tandem with it. Electronic and print and their respective work and joys, their strengths and weaknesses, will co-exist because they aren’t a zero-sum game so much as complimentary, additive—a positive-sum game in which we all gain a new storytelling medium. I’m no mathematician but it may in fact be an infinite-sum game. The opportunities are just that boundless.

photo by accent on eclectic

Besides its effect on literary intimacy, the flip side of inserting social media into art is why the internet was invented in the first place: it shall foster sharing. Not merely the sharing of active e-readers’ favorite excerpts but their thoughts and questions, and more importantly, not just amidst e-readers, but with the authors themselves. Consider the open dialogues that will occur between writer and reader below the work that has brought them together. No longer one-way, this level of interaction will only strengthen ties (and, ahem, accountability) between authors and their audiences. The resulting literary community will expand geographically but contract socially, our global interconnectedness condensing with every conversation until publishers and authors are less city hall and mayor than a reader’s neighbors in the village; dialogues opened not through votes and ballots but communal town halls and front-yard wave-hello’s. All this will make marketing future works more effective—not by geo-targeting or viral network effects but honest-to-goodness feedback. The brilliant hermit author will always be a sexy enigma but the social e-author will be a perfect counterpart: temptingly close.

Those future works have intriguing destinies, depending on who you ask. Penguin Books CEO John Makinsonis recently told the press that “the definition of the book itself is up for grabs” and his company is betting big, crafting multiple tiers of interactivity for a variety of age groups and imprints. Readers will be treated to games, 3D graphics, audio, and video on books so robust they can’t be listed in the iBookstore but require their own standalone applications. Book designer Craig Mod recently told the New York Times that “[t]he metaphor of flipping pages already feels boring and forced on the iPhone. I suspect it will feel even more so on the iPad. The flow of content no longer has to be chunked into ‘page’ sized bites.”

photo by Jenny Downing

So beyond redefining how readers share and work and interact with narratives, e-books won’t end there, not just redefining but reconstructing. With horizontal page-flipping a thing of the past, the navigation of narrative is free to experiment broadly—a vertical tower to scale, a user-controlled ‘quilt’ to traverse, a coiling helix to scroll, a 3D world to explore.

Of course, with all these possibilities, publishers will need to juggle the creation and exploration of their new medium against the continued demands of its print-based forefather. With Barnes & Noble already reshuffling its leadership team and rebranding itself a “digital and technology company,” writers and readers are right to worry that publishers might push their money, time and resources into this new species of narrative at the expense of paper and ink. But to do so would be a mistake, for these two forms will live on, side by side, complimenting each other, expanding on one another’s narratives, and, ultimately, providing its shared audience with the option of not just one or the other, but both. Vespa owner or cyclist, wind surfer or sailor—like electronic or print, these are choices that will fluctuate over time, and not just for consumers and creators, but the businesses that connect them. Binary Bookmaking will never require binary business strategies. There will always be choice.

photo by LIS-Corner

E-readers, if executed properly, will be about just that: choice. The choices of pure text or rich; multimedia color or e-ink black-and-white; interactive or linear; isolated or social. E-readers, if executed properly, will be the premiere platform for a new form that will have less in common with the novel than with the web-narrative. The film industry that once began as recorded theatre now boasts special effects and narrative devices never dreamed of by its inventors. E-reading will evolve just as elegantly; not for itself, but for a new generation of audience that demands more than simply immersion, but interactive immersion. Open immersion.

Rio Player / photo by nrkbeta

In the early 1990s there was a music file format called .bit. You might remember .bit because it hung around for just that, eventually giving way to another format we know a little more intimately: MP3. Listening to these early music files required the program WinPlay3, a program you might also remember for it was the MP3-playing predecessor to Winamp (1997) and, eventually, iTunes (2001). The music industry ignored .bit. They ignored WinPlay3. They ignored all these developments for the better part of a decade until a little company called Diamond Multimedia came along and built the Rio, a first-generation portable MP3 player that paved the way for the iPod. Only then, once MP3s had literally changed the landscape upon which their art was consumed, did the record companies make their demands for a piracy-free solution. A demand for protection of their bottom-line, not exploration in how that bottom-line might prosper under the ecosystem installing itself into their industry. Not fortification, not treaty, but a demand for protection.

The e-book’s future lies in the hands of publishers who at one point would have liked nothing but to abort it. For a variety of reasons but most of them monetary, such as the economy of e-books in relation to bound, and what that trade-off might do to the costs of maintaining pricey bricks-and-mortar stores, not to mention compensation for the authors and poets that fill them with such wonderful words. All fatalism aside, there was and never will be an aborting of this e-movement, and success—not just survival—awaits the players who embrace it versus those who protect themselves.

The transition from bricks-and-mortar to e-commerce shouldn’t scare, as it doesn’t complicate matters so much as open them up. The New York Times recently reported that the e-book is in ways more profitable for publishers and writers than print, but the article was more a snapshot of today’s competitive landscape and economics than a look forward to what lies ahead. Not the gradual tectonic shift of print into electronic, but, as argued here, a whole new continent born from the water, built to satisfy the needs of artists and audiences growing up in a digital world. This ecosystem’s birth will be less erosion than explosion, giving articles like the Times’s all the long-term significance of a ballgame’s box-score. Because Binary Bookmaking affects more than simply margins. It impacts art. It impacts audience. Hard things to quantify with dollars, but as the music industry has shown, anything less than full-on engagement will be far more costly in the long run.

This isn’t happening overnight—we find ourselves in the .bit stage, not the MP3. There is plenty of time for publishers to adapt, to reorient their personnel, to reevaluate prior investments and strategies. More than simply prudent, these decisions can be lucrative. Whole new business models and promotional tools lie at publishers’ disposal; incredible targeting and profiling capabilities now exist for intra-device advertising; fresh pricing structures, not just for books, but for stories, can now entice a broader array of demographics. Simply put: there will exist as many business opportunities for the creative publisher as storytelling opportunities for the creative author.

iBookstore / photo by nrkbeta on flickr

Of course, there are still economic negotiations to iron out. Amazon, hoping not just for new content but a new price ceiling, has rolled out its 70% royalty program for authors interested in self-publishing, allowing them a huge spike in revenue earning-power but against unit sales priced 20% below the lowest physical list-price—a maximum of $9.99. We’ve all heard about Macmillan’s stand and the resulting blacklist and backlash. The iPad’s pricing structure only fans the flame of this price war. But these are the first moves in a marathon chess match—a few pawns placed long before the game’s true tactics illuminate themselves. As it always has, the market will dictate demand. Prices will fluctuate until consumers are content with the value an e-book provides against the price they are paying for it. Don’t forget: e-readers are already offering totally free content, and this is how many authors are grooming readerships and promoting future releases. Few authors can write for free forever but their decision to do so even temporarily ensures that the $15 e-book can’t last forever—the market will adjust and solely-text based e-books simply won’t be worth that much anymore. Richer offerings will be worth their riches. Just look at the current iPhone App Store, which already has more Book applications than any other genre, including Games.

The rise of e-literature introduces a new art form that will require a new way of doing business just as it will require a new marketplace in which to do this business. Rather than plunk down one payment, revenue can now be obtained piecemeal by publishers who price functionalities like social reading, interactivity, and multimedia into tiers. Unlike the MP3 and its DRM tiers, these would be content-based, not quality-based. For those emerging authors looking to develop a fanbase with free text offerings, the value of free text might transition from author awareness to author engagement as readers look to pay for the kind of immersive extra features that only e-narratives can provide. Beyond those features, e-books will also provide writers with new ways of building buzz for their creations with tactics like personal interviews, complimentary stories or poems, playlists to accompany text, video trailers, access to real-time bookclub conversations, embedded videos, links, and other special content. Needless to say, the costs of doing business in this new marketplace will change. Publishers will still require editors, publicists, marketers, and designers, but will also need a talented team of coders, graphic artists, animators, and programmers. These things will add cost, but the wealth of sales data that circles back will allow publishers to tweak and optimize the formula, particularly in terms of pricing and offerings. This is, in the end, the greatest gift e-readers will provide publishers: instant feedback. What extra features were readers most willing to pay for? What stories or poems or sections of novels were shared and commented on most? This data will result in optimization, a requirement should the commercialization of e-literature match the creativity with which it is constructed.

Now, many authors will see these strategies and commercialization as damaging to their art. Or, if nothing else, feel that it’s a waste of their time. After all, every hour spent collaborating with e-book programmers or video-chatting with book clubs or producing YouTube walking-tours of the place where your book is set (as Colson Whitehead did in 2009 for the release of Sag Harbor) is one less hour spent at the keyboard. These are valid concerns. But the truth is that writers in this next generation may not have the luxury of isolating themselves from a public that has developed a taste for transparency and immersion. In the same way that Mass is no longer delivered in Latin in most churches, this new congregation wants to be included in the process, not held at arm’s length.

And, frankly, perhaps we should immerse ourselves in the culture if we wish to truly understand it. Isn’t that our role as artists? Just as the Modernists captured what it felt like to live in their era by allowing the time to shape their work and words, perhaps twenty-first century authors need to do the same. Because whether or not we like it in our writing toolboxes, interactivity is a major part of life in this new age. Embracing it might not only allow us to reach new readers and push the limits of our writing, but make our writing and stories more relevant. After all, how can we say something about our society if we’re unwilling to engage it?

In more practical terms, however, the e-movement is particularly beneficial to writers due to the expansion of their playing field. The MP3 age may have hurt the bottom line of mammoth music publishers, but it allowed an incredible new generation of experimenting musicians to earn their place in the limelight. Similarly, independent publishers and their authors will find this new open landscape to their liking. Rather than remain in obscurity because they lack the advertising budget of a major house, public awareness of an author’s work is more likely to be determined by what should have been most important in the first place: his or her art. This digital age of sharing and social networking ensures “word of mouth” can stand tall against big budgets. Instead of being bound—pun intended—by the constrictions of traditional publishing, the work of talented independent authors will be accessible in a variety of ways: single story or a whole collection; serialized chapters or an entire novel; multimedia or plain text. The layered, detail-rich stories these teams are already masters at will become more accessible to an e-generation that appreciates exactly what they provide: content for them to share and discuss and discover.

Of course, as in music, the ease of e-publishing may bring with it a fair amount of sub-par work. It may stretch editors already stretched thin. But this more open marketplace will be inherently more democratic. The best stories will win. They will, at least, breathe. E-publishing won’t change our institution from a public entity to a private one; rather, it will be the digital format’s accessibility and distribution, its ability to be shared and interacted with. In many ways, the Age of Binary Bookmaking just might coincide with the age of a new independent publisher—one that is as nimble and hungry as the new readership that awaits it.

photo by cloudsoup

Everything has begun to change. Reading, sharing. Publishing, distribution. Advertising, pricing. And as all this unfolds, the book, our beloved suffixed book-book, will remain anchored in time. Not trapped inside the e-age sediment but down beneath it, forming a foundation for everything e-storytelling might deliver. A warm crust, nourishing from below, sending up streaks of energy and vitality. The printed book need not be threatened by this new e-specialization because it provides all the nutrients making it possible in the first place—Mother Earth breathing life into new species of writer and reader. Granted there may be fewer printed books in the e-age ahead, but they will be bolder and more assured for allowing a new member into the family.

Further Resources…and Questions

- What of the fractured data formats governing each e-reader—who will hold the e-standard in perpetuity? How does the education system take advantage of these developments? What happens when children who already spend eleven hours a day in front of a screen abandon the pages of a book for an e-reader? And, of course, what will become of our Atomic Priesthood clergy now that the Yucca plan has fallen victim to budget cuts?

- Even as e-reader technologies converge into each other with incestual twists like LCD screens that convert into e-ink displays, can a Kindle/iPad mongrel inspire new readership while keeping its original one engaged?

- Experiments in interactivity are already underway in movie threatres via “Last Call,” a film by 13th Street, who have created a customized multilinear narrative in which the audience calls the shots on their cellular phones via direct dialogue with actresses in peril:

- See more of Craig Mod’s sharp, stylized vision for the future of e-books here.