James Magruder was one of the first people I met when I moved to Baltimore in 2008–it was at a writerly gathering at a pizza joint in Station North. He is whip smart, like award-winning-translations-of-French-comedies smart. It’s a quality that might be dangerous in someone capable of arrogance, but Jim is as kind and self-deprecating as he is bright. Even while he’s devoting himself to his husband, Steve, and to his MFA students and undergraduates, he provides feedback on many writer friends’ manuscripts (including mine), and he tutors at a nonprofit that helps city kids with their reading skills. If all that weren’t enough, he does wicked impressions of Amy Sedaris from Strangers With Candy.

Jim’s versions of Molière, Marivaux, Lesage, Labiche, Gozzi, Dickens, Hofmannsthal, and Giraudoux have been produced across the country. He also wrote the book for the Broadway musical Triumph of Love. After fifteen years in show business as a playwright and dramaturg, he turned to fiction. His debut novel, Sugarless (University of Wisconsin Press), was a Lambda Literary Award finalist and was shortlisted for the VCU Cabell First Novelists Award and the 2010 William Saroyan International Writing Prize. A story collection, Let Me See It, was published in 2014 by TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press.

His latest, Love Slaves of Helen Hadley Hall (out this month from Queen’s Ferry Press), is told from the perspective of the woman in a portrait that hangs in a Yale dormitory named for her. The novel is in first-person, but reads like third-person omniscience because old Helen knows everything about every kid who comes through the door. The story focuses on the residents in 1983-84, a time when the AIDS epidemic was ramping up, which doesn’t sound like it would be a hilarious read–but it totally is.

Jim and I spoke recently at his walk-up apartment in Charles Village, a recorder sitting on the Queen Anne candle stand.

Interview:

Kathy Flann: Your theatre background and your Broadway background are not the usual path for a fiction writer. It informs my understanding of you, but someone meeting you for the first time might find it surprising.

James Magruder: It’s like finding out you did stand-up comedy.

Right!

To me, writing fiction has always been the highest calling. Plays happen so quickly, but stories take forever to write, so I always feel like prose fiction is the highest, highest thing of all. Anyway, I got my doctorate at the drama school (at Yale) by translating French plays. So I mixed the French and the drama together. I got a job working as a dramaturg in La Jolla. And I left before I drank the Kool-Aid. I wasn’t happy. I tested positive for HIV and thought I was going to die. The West Coast was too relaxed and I felt I couldn’t live up to the weather.

So you came to Baltimore?

Baltimore Center Stage offered me a job. Part-time. Because they had a shift of artistic leaders. I think this was 1991. I said, “Sure!” The artistic director, Irene Lewis, and I really hit it off. She gave me a home. When my health improved in 1997, I thought, Well, I’ve got to fulfill my early promise–oh, but in the meantime–this play I’d translated, Triumph of Love, had been done at Center Stage and then it was done off Broadway at Classic Stage. And the way these things go, it was like, “Let’s make a musical out of it!” It was up on Broadway in October of ’97. We were unlucky that Ben Brantley did not enjoy our particular brand of camp. We had lots of good reviews and a starry cast. It still gets done a lot–anyway, quack, quack. So that was Broadway.

How did that experience help you or change you?

The thing I learned from working on Broadway is that you can’t be precious. If the producer says, “We need a better joke” or “This isn’t working,” you just do it. With writing for theatre, I had the biggest kind of pressure cooker. If Brantley had liked my little show, I would have had a very different kind of life because I would have moved to New York and probably failed and would not have started writing fiction and would have consumed all of my energy being jealous of other playwrights. And I wouldn’t have met my Steve! Broadway was a great gift because I never set out to do that. I have no… I only feel good about it when I think about it.

So I went back to Baltimore, and I thought, You’re going to live. I started writing short autobiographical plays that were gathered into an omnibus evening in 2000 called Bad Beans at Baltimore Theatre Project. Sarah Schulman, of all people, saw these four plays and said, “Be courageous. Put them all together.” And I said, “No fucking way!” I wound up going to MacDowell to work on a full-length play that did sort of combine all the Beans, and while I was there I wrote my first piece of short fiction. In the meantime, I had also started Love Slaves.

Do you think that Love Slaves owes anything to Triumph of Love?

Do you think that Love Slaves owes anything to Triumph of Love?

One of the reasons it was such a long process, seventeen years, is because I started out without really knowing what I was doing. I knew the theatre really well. So Love Slaves was overpopulated. And it was lots and lots of dialogue. And there was no narrator because in a play, there isn’t, unless you literally write a narrator into your play. That’s been around since the chorus of the Greeks, but contemporary playwriting doesn’t usually have narrators. In a play, everybody is his or her own narrator. Love Slaves was like this kind of Altman movie. In a way, there was no protagonist, and it took me years to figure out that wasn’t going to fly. But the sense of comedy. Certainly.

Yeah, because stuff that’s meant to be performed–the pace has to be so fast. And I wonder if you feel like that has helped you.

Actually, that’s totally true because you can’t bore an audience. You can bore your reader a bit because they can skip ahead, they can skim. You don’t want them to, but it’s always the present moment. And so when I was writing Love Slaves and Sugarless, I consciously, more than most fiction writers do, thought of each chapter as a scene. Something had to happen to move it forward. End of a chapter, you had to want to move. A decision had to be made. I was very conscious because after years of reading plays for Center Stage and working on them and trying to make them better, you can’t. There’s no room, and there’s less of it in contemporary fiction than there used to be–you can’t spend three paragraphs describing the woods. I know I can’t. So the things I missed by not having an MFA, the things I had to develop–I had those in my back pocket, as it were.

Right, maybe even more so.

To create a scene or use dialogue or know when something needs oomph. I don’t want to be, like, We’re just idling here. Which I see in my students’ writing. It’s like, “Nothing’s happening here.”

Right, exactly. We probably spend all of our lives, when we’re teaching, with that one problem. That’s something I’m reflecting on a lot right now, at the end of the semester; it’s that one problem you talk about with almost every student you have.

Yeah. Nothing’s happening. As much as I love language, there has to be action.

Another risky business in Love Slaves (in early drafts) was its fancy pants diction. Who is this narrator, speaking in this 18th Century, Henry Fielding, Rococo prose style? Why is this person spending all of this time with these fools (the dorm kids)? These immature, brilliant idiots?

Well, she’s so arch and she’s so funny. And yet, you do keep a contemporary register. It’s not inaccessible, by any stretch, to a contemporary audience. So I was wondering–who do you think your influences are, both contemporary and from the past?

Well, I could have saved myself a lot of time if I had actually read The Lovely Bones. Because it took me fifteen years to find my posthumous narrator, Helen, who’d always been there on the first page. Finding her sort of solved two problems at once. I had a narrator who could be in everybody’s head because she’s an ectoplasmic emanation–although she picks her favorites. She doesn’t follow everybody. And the other is that she’s 117 years old and has been listening, sitting in her portrait from 1958 until today, so she knows all the lingo, and she loves, loves using the lingo. So it solved the ornate prose and the omniscience problem.

Well, I could have saved myself a lot of time if I had actually read The Lovely Bones. Because it took me fifteen years to find my posthumous narrator, Helen, who’d always been there on the first page. Finding her sort of solved two problems at once. I had a narrator who could be in everybody’s head because she’s an ectoplasmic emanation–although she picks her favorites. She doesn’t follow everybody. And the other is that she’s 117 years old and has been listening, sitting in her portrait from 1958 until today, so she knows all the lingo, and she loves, loves using the lingo. So it solved the ornate prose and the omniscience problem.

Oh, but my influences–I love Dawn Powell, and I would say Forster because I think he writes amazing sentences. Certainly an influence for everything I do is John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. It too has multiple interweaving plots that wind up in one spot. And I think my training as a writer of theatre comedy and a dramaturg–you should sort of aim for, at the climax, all of the people are ideally in the same room.

It is so funny. Your stuff is generally funny–your plays and your fiction–and I wonder if, in this book, because of the scope of it, were you able to do things with your humor that were different from some of your other projects.

Sugarless is much simpler. I’d deliberately made that narrator a C student. Average. And then, through what happens to him, he blossoms. But Love Slaves is like the most smarty pants I’ll ever get. It suffers from a sort of smarty pants.

Or prospers from it!

It’s not for everyone’s taste, but if you have a sense of humor…. [Laughter.]

My sense of humor is A Confederacy of Dunces and Jean Shepherd, who wrote for Playboy in the sixties, and then collected his essays. He wrote really funny, autobiographical things about growing up in the butt-end of Gary, Indiana, which is already a butt. That terrible movie A Christmas Story, that everyone loves so much, is based on one of his stories.

Oh, I did not know that!

He has these two volumes I read when I was twelve, and I still, if I’m in a bad mood, will pick up Wanda Hickey’s Night of Golden Memories.

The third big influence was City Boy: The Adventures of Herbie Bookbinder, by Herman Wouk, who’s still alive at 98.

I found it in eighth grade, and I still laugh myself sick with it. The DNA of Wouk’s sense of humor in City Boy is me. I blame him. I wish I could say my greatest influence was Cervantes, but….

You probably have different influences for different aspects of you. You’d probably say something different about “What are my influences for writing in the third person?” or what have you.

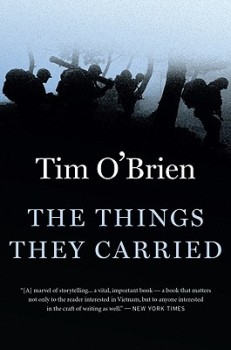

I just posted on Facebook yesterday, “Am I the last writer in America to read The Things They Carried?”

I just posted on Facebook yesterday, “Am I the last writer in America to read The Things They Carried?”

Oh, what did you think?

Well, I was destroyed by it! It is as they say. It is all that. Unbelievable. By then end you don’t know what’s true but it doesn’t matter.

What does it mean to have Love Slaves of Helen Hadley Hall coming out after all this time?

It’s been a rough couple of months because Steve has had deep-vein thrombosis and I’m waiting for one of my plays to get done. And I’m procrastinating on some other projects. And I found a bump on my foot, and I thought, I hope this is Stage 4. [Laughter.]

Because in a way with Helen Hadley coming out, it’s like, “Well, I could just die now,” [Laughter.] Everything I’ve ever wanted to say–for me it’s in there. It’s actually hard for it to be over.

It’s so ambitious and its vision is so large. But it’s still so approachable. I mean, it’s so fun. I can understand why you’re saying what you’re saying because you have this scope and yet this intimacy. It’s hard to pull off, to have both of those things.

Well, thank you, Kathy, for saying it has scope because in my mind, it’s just one little eight-month period in an academic year.

But it feels like it’s got this lens that goes everywhere and in everyone, all the characters that are not only in the room, or in the building, for those eight months, but also because of this narrator that sees things constantly, she can bring in that perspective as she looks at this small group.

I suppose that’s what we all want to know. We only get to see our own lifetimes and we want to know, How do we fit in over the larger scheme of things? It’s almost like that fantasy of knowing.

Right, and that’s one of the reasons why I don’t ever want to leave that dorm. That’s why I deliberately left the last coda in the present tense, so it’s always happening.

It’s always happening. Yes! I love that.

And it wasn’t until the long last grind of rewriting that–so much time had passed–that it became a historical novel. I started it at age thirty-six and finished it at fifty-three or fifty-four, and it’s set in 1983. I wouldn’t have been able to realize, starting out in 1996–and I’m not George Eliot or Jonathan Franzen or Dickens–but we can see what Helen’s politics are and we can see what she decides. People say Reagan killed the middle class. Well, Reagan did kill the middle class. Fiscal promiscuity took the place of sexual promiscuity. What we’re experiencing right now was laid at the same time as the virus was discovered. The virus of greed–it continues unabated. I touch it lightly, but I like to think when all is said and done, she’s got some wisdom.

I think she does. That’s what I mean by the scope and ambition. But it doesn’t feel like you’re trying to tell us a message or something. It’s coming from her.

I started to write a sex romp. [Laughter.] But really it’s about what it’s like to be young and foolishly in love and you go after it without any perspective. These characters are very self-conscious. They’re always looking in the mirror. It’s quite a motif. But it’s when you wanted things that bad. And all these things are whispering, This is not a good idea, this is not a good idea. But you just squelch them. I think this can speak to anyone who has been a fool, an absolute idiot for love.

So that brings us back to Triumph of Love! You’ve conquered two different art forms.

Well, I don’t know about “conquered.” I’m still chipping away at it.

Yeah, this acting and dramaturgy stuff is tough. I’ll do something easier. I’ll write fiction. [Both Laughing.]

[Silence for a moment.]

Everything can be a story.