“The people who live in this land are the people I’ve known best throughout my life, and together with the country we live in, they form a vast well that will never run dry.”

–Larry Brown, “A Late Start in Mississippi”

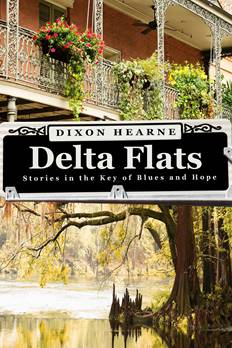

Dixon Hearne writes in the American South, and is the author of several recent books, including Delta Flats: Stories in the Key of Blues and Hope (Walrus Publishing) and Plantatia: High-toned and Lowdown Stories of the South (Southeast Missouri State University Press), which was nominated for the PEN/Hemingway award and won the Creative Spirit Award for best general fiction book. His work has been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has received numerous honors. He is also editor of several anthologies. His work has been published widely in magazines, journals, and anthologies, including Oxford American, New Orleans Review, Louisiana Literature, Big Muddy, Post Road, New Plains Review, Mature Living, The Southern Poetry Anthology and elsewhere. He is aided by his incredible bichon, June.

I first “met” Dixon after he contacted me to tell me he had read my second novel, Harlow, and subsequently offered to interview me for Belle Rêve Literary Journal. I agreed to sit down with him—now almost two years ago to the day—never suspecting that many more interviews and correspondences were to follow. These were made all the richer by the development of a great friendship and literary companionship, all springing from our shared love of language and storytelling.

Interview:

David Armand: Thanks for sitting down with us, Dixon. I was wondering if you could start by telling us how you came to writing. Your background isn’t in writing, per se, but you come from a tradition where telling stories is integral to the culture.

Dixon Hearne: I’m not your “typical” writer—if such a thing exists. I hold no MFA degree. I have never taken any courses in creative writing. And there was certainly no place in my high school curriculum to nurture such interests. I graduated from a liberal arts college, with a degree in English and history, which I taught for several years before I received my doctorate and threw myself into academia.

I didn’t start out to be a writer. I just sort of caught it one day—like religion. By that time I had made a respectable contribution to education journals and magazines. I had served for many years on the editorial boards of education/special education journals. But it was no longer fulfilling; something was missing. I wanted to try my hand at writing in a “different voice.”

On a whim, I sat down one day and began writing a short story. The result was a humorous tale about a traumatic event in the life of a young boy in a small southern town. I sent it off to a couple of literary journals, and a month later I received a call from an editor who told me that my story had been awarded the Editor’s Prize—and a check would be forthcoming! The bigger thrill for me was that someone actually read my story. It has remained so—even when I receive the inevitable rejection.

Do you remember which journal that was?

Yes, it was Reflections Literary Journal—which I picked at random from a list in Writers Digest.

Were you reading anything other than academic journals then? If so, what were you reading?

I was reading only biographies and other non-fiction at the time. I had read very little fiction since my undergraduate days (even then, it was the standard requirements for British and American literature).

Then what happened after that first publication and award?

By this time, I had discovered that writing short stories was a whole lot of fun. I had sent three more stories out for review, and two of them were accepted within a couple of weeks. This was very encouraging. I had an inexhaustible imagination for creating stories about my childhood growing up along the rivers and levees, about travels with my father along the back roads of northeastern Louisiana when I was a young boy. We visited small towns and country stores, where customers and merchants whiled away the day talking about politics, farming, the weather, LSU football, and each other. They all seemed to love spinning yarns and one-upping each other. Their voices still echo in my mind. Most of my stories are set in this culturally-rich and beautiful region. I often quote Faulkner who felt the same way about his own “postage stamp” of reality as the source and inspiration for much of his writing.

And I’m assuming, like Faulkner, you’ll never live long enough to exhaust those wonderful small town stories, right?

And I’m assuming, like Faulkner, you’ll never live long enough to exhaust those wonderful small town stories, right?

Of course. There are more stories than one could tell in several lifetimes—and all of them just waiting to be told.

OK, so I’m also interested, specifically, in how you’ve been able to be so prolific lately–publishing just in this past year a novella, a collection of short stories, as well as a collection of new and selected poems (a monumental accomplishment in and of itself) forthcoming.

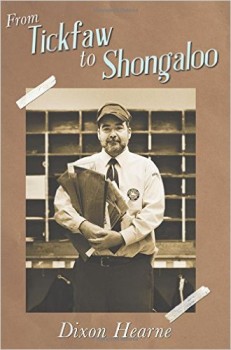

Ah, this is an easy one. Most of my novella, From Tickfaw to Shongaloo, was written as shorter, stand-alone pieces—most of which were incomplete. One particular story, “Sister-Woman,” was my inspiration for weaving all these short tales together into a cohesive story. “Sister-Woman” was one of my early stories—a humorous tale told by a middle-aged spinster who never seems to tire of talking about folks in her hometown. She kept on grumbling in the back of my mind until I decided to turn the whole thing over to her. The result: I submitted this novella to the 2014 William Faulkner-William Wisdom writing competition, and it was awarded sole Runner-up in the novella category, judged by Moira Crone. It was then published last summer by Southeast Missouri State University Press.

As for my new short story collection, Delta Flats: Stories in the Key of Blues and Hope, all but one of the stories have been previously published in magazines and journals. I was quite blessed that the first publisher I approached offered me a contract. The book has recently been made available.

As for the poetry, I do not consider myself a poet—by any definition. Most of my poems are snapshots and snippets and personal reflections. My heart is clearly lost to my native South, but my soul also roams the Great Plains and the deserts of the Great Southwest. I love writing about the connections between peoples and their lands, about their cultures and their world views. This comes most easily to me in poetic form.

My new poetry book, Plainspeak: New and Selected Poems, reflects these personal interests. The book will be released Fall 2016 by Aldrich Press. Like my short stories, all but a couple of the poems in this collection have been previously published in magazines and journals. And once again I am blessed that this collection was also accepted by the first publisher I approached.

I alternate between writing fiction and poetry. I like to have several pieces going concurrently.

It’s interesting that you say that you alternate between both fiction and poetry. Most writers I’ve spoken with say they have to focus on one project at a time. Do you find it helps you to have several irons in the fire, so to speak? Do you adhere to a particular schedule when writing, perhaps devoting specific blocks of time to one genre and then another?

When I write, it is because I have something that needs to be said right then. I cannot imagine a daily schedule for writing. I’m not made that way. I recall reading that both Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote set aside specific times daily to write—and all else must wait. What self-discipline that must require. Of course, that reflects their zone of comfort, their habits of mind.

Once I’m moved to write, I can get my thoughts onto a tablet pretty quickly—whether fiction or poetry. Poetry writing always begins with an image that engages my senses. I can see, smell, feel, and hear clearly—all to a heightened degree. Many of my stories come to me fully realized, that is, from beginning to end. In this case, all I do is try to get it recorded before the voice disappears. Other times, stories unfold in parts. I rarely have to marshal a piece to completion. Of course, this results in some pretty “non-literary” work.

Most of my stories begin with a voice or a character. My imagination grants me access to them. It is as if I’m standing right there with them listening and watching their stories evolve. I can see them clearly, hear every nuance of their voices, and describe the setting quite clearly. I love the diction, the accents.

Most of my stories begin with a voice or a character. My imagination grants me access to them. It is as if I’m standing right there with them listening and watching their stories evolve. I can see them clearly, hear every nuance of their voices, and describe the setting quite clearly. I love the diction, the accents.

I think I could be characterized as an intuitive writer. I rather like Ray Bradbury’s quote on this: “Your intuition knows what to write, so get out of the way.” I do not use a lot of clever literary devices in my writing, mostly because I write simple stories which, to my thinking, should be told with simple language in a simple way. I admire well-executed literary devices, so long as they complement the plot and “telling” of a story. I especially admire writers who can effectively use “flourishes” of brilliant language in their stories—rather like rich frosting on a cake. Too much,though, and the thing is ruined.

My weakest area is revision. Once I’m through telling a story, I’m basically through with the whole thing. It does not make for great literature. Fortunately, I have no pipe dreams about becoming a great writer.

As for alternating between genres, I believe that writing poetry aids me in summoning “exactness” in my prose writing when it is needed. Likewise, when I feel a poem coming on, I just get all my thoughts onto paper in prose form. I’m then able to tinker the thoughts and words into poetic form. The two processes complement each other admirably.

I write the occasional essay, as well—typically column-length work for newspapers or anthologies. I enjoy this for a change. It allows me to revert back to writing with a “voice of authority,” the voice I used for years writing for education journals. This too, I believe, has contributed to my writing of fiction and poetry.

I’m glad you brought up the idea of academic writing versus creative writing. I had planned to ask you about that anyway, but since you just mentioned it, could you elaborate a bit more on that? Obviously, there’s a great difference between the two–both in the composition of and then in the submitting of said work for publication. But, in your experience, have you found one form of writing to be particularly more challenging than the other? And what about the publishing aspect? Do you find editors of literary journals to operate differently than those of academic journals? Without incriminating anyone in particular, is there one you prefer (in terms of the publication process) over the other?

By the time I received my Ph.D., I had already conducted quite a bit of research and published it in some of the leading journals in my field. Writing for education journals follows APA style (American Psychological Association), which does not allow for creative writing—unless, one considers the discussion section an opportunity to demonstrate a bit of flare. I had to “rethink” my way through the process at the beginning, as it runs contrary to my own way of constructing meanings, which is by nature more intuitive—thinking and knowledge not valued by scientific research. I was fortunate to have had so much of my work published—and to be tapped to serve on editorial boards.

Very few literary journals hold writers to the same “blind review” scrutiny as science/social science magazines and journals. I was shocked (and amused) when I first discovered this fact. It seemed to account for why I kept seeing the same names in the best places. I actually wrote an essay taking this matter in hand. It was rejected quickly by ten journals—only one offered a reason. Most submissions to education journals receives a reading by at least three qualified persons, and their reviews are compiled into a detailed response to the submitter(s). One of the first comments I read by an editor of a literary journal advised the writer to “try another journal if you’re not already known in literary circles.” I didn’t submit there.

In terms of the ease or difficulty between writing fiction and academic writing, I find creative writing to be easier and inherently more interesting. What qualifies as “quality literature” is purely subjective—just as meaning in art is negotiable. As for the difficulty of getting published, I must say that research journals are much more objective and fair in their review process.

You’ve mentioned several times now this idea of what qualifies a work as being “literary.” I agree with you that this is a highly subjective endeavor, but I’m interested in your statement earlier in which you referred to your own work as being “non-literary.” Yet you’ve been published in some pretty esteemed literary journals and have received stellar endorsements from writers who are, without a doubt, literary writers–Moira Crone, John Dufresne, Tom Williams, and a whole slew of others. I read, for example, where John Dufresne, in reference to your novella From Tickfaw to Shongaloo, said, “Dixon Hearne has taken up the estimable mantle of Southern comic writers that stretches back to George Washington Harris and Mark Twain. Digressions are the sunshine of this hilarious novella, and you ll be reminded of Eudora Welty and Laurence Sterne. I haven’t laughed so hard since A Confederacy of Dunces.” That’s high praise.

You’ve mentioned several times now this idea of what qualifies a work as being “literary.” I agree with you that this is a highly subjective endeavor, but I’m interested in your statement earlier in which you referred to your own work as being “non-literary.” Yet you’ve been published in some pretty esteemed literary journals and have received stellar endorsements from writers who are, without a doubt, literary writers–Moira Crone, John Dufresne, Tom Williams, and a whole slew of others. I read, for example, where John Dufresne, in reference to your novella From Tickfaw to Shongaloo, said, “Dixon Hearne has taken up the estimable mantle of Southern comic writers that stretches back to George Washington Harris and Mark Twain. Digressions are the sunshine of this hilarious novella, and you ll be reminded of Eudora Welty and Laurence Sterne. I haven’t laughed so hard since A Confederacy of Dunces.” That’s high praise.

Yes, I was so pleased to see John’s endorsement. He has been such a keen supporter of my writing.

On top of that, your work is consistently published by university presses and other publishers of high quality, i.e. “literary,” work. So at some point, you have to acknowledge your work’s literary merit, right?

I just meant that I do not write works of great literary quality—certainly not in the tradition of a Hemingway or Faulkner or Steinbeck. As I said, I have no delusions of grandeur in the literary world. However, I am struck by the various comparisons of my work to respected writers: Twain, Welty, O’Connor, Edgerton, and others. We all write primarily about simple people in complex situations, but I don’t have the literary genius they possess to raise literature to the level of art. It was never my objective to even try. It is a very special gift they possess—but, with assembly required. I’m content to appreciate their work without any impulse to study or mimic or adapt.

One particular comparison has caught my attention. When I wrote my short story, “Sister-Woman,” I had never read Eudora Welty’s short story “Why I Live at the P.O.” When a few people pointed out similarities between our narrators, I sat down and read her work. I grew up 120 miles due west of Ms. Welty’s home. Being from the same “neck of the woods,” it should be no surprise to any reader that we share a common cultural and linguistic heritage—as well as the same population from which we draw our characters. I love the narrator in her story. I feel as though I know her personally, and I think she and Raylene Peep [narrator, From Tickfaw to Shongaloo] would be close friends.

Speaking of your novella and its narrator, Raylene, you mentioned first hearing her “voice” and then essentially recording that voice until it was finished saying what it had to say. Given how different Raylene’s voice is from your own, how difficult is it for you to channel a particular character like that? Do you feel as though you’re acting as a sort of ethnographer, transcribing a culture’s stories, or is it something different?

Characters’ voices are always vivid in my mind. I can hear them speaking “clear and plain.” Sometimes it is like we pick up in the middle of some longer story already in progress, or we begin a new chapter in that story. Somehow I quickly sense the general direction of the plot, and background details just seem to fill themselves in like water between cracks. Before I know it, I’ve been appointed scribe. Faulkner says it better: “It begins with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.” This is how I know a new story is coming on. I wonder how many writers share this same experience.

I’ve been told by several authors that I have a “good ear for writing.” I think that is because I’m so attracted to the language of conversation. I seem to capture that in my writing.

Well, since we’re running short on time, Dixon,I think readers might be curious about what you’re working on right now–any readings/signings in the works, any other interesting writing projects?

I’m presently working on a novel set in New Orleans—and more short stories, of course.

I will be on a book-signing tour in the coming months, promoting Delta Flats and From Tickfaw to Shongaloo. I will deliver the keynote speech at a writing conference in Missouri in July, and I hope to present at other literary gatherings this year.

Well, I know wherever your readers might run into you, they’ll be in for a real treat. It’s definitely been a pleasure talking with you, Dixon.

Thank you.