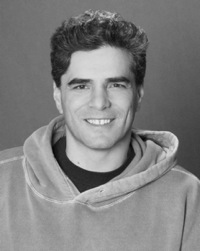

Jeff Kass declares, “I’m always sure I’m not the cool kid.” Yet this self-proclaimed “hopeful knucklehead” manages to exude nothing but crisp calmness and dazzling humility to students, friends, and readers alike. Jeff’s writing illuminates truth and illustrates his belief that despite making mistakes, we all deserve the opportunity to become better versions of ourselves. His honesty is infectious both in the classroom and on the page, convincing students and readers to carry themselves with similar promise.

Jeff Kass declares, “I’m always sure I’m not the cool kid.” Yet this self-proclaimed “hopeful knucklehead” manages to exude nothing but crisp calmness and dazzling humility to students, friends, and readers alike. Jeff’s writing illuminates truth and illustrates his belief that despite making mistakes, we all deserve the opportunity to become better versions of ourselves. His honesty is infectious both in the classroom and on the page, convincing students and readers to carry themselves with similar promise.

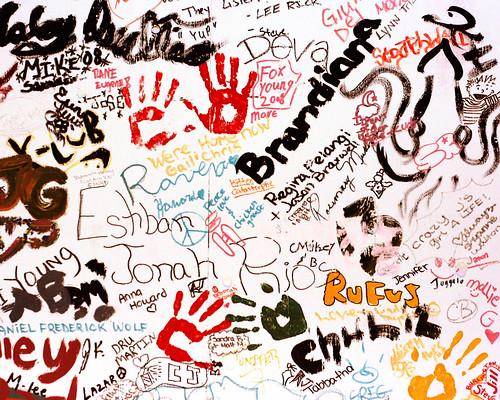

Knuckleheads (Dzanc, 2011) is Jeff Kass’s first collection of stories, following a chapbook of poetry, Invisible Staircase, a chapbook of essays, From the Front of the Room, and his one-man poetica performance, Wrestle the Great Fear. Inspiring and motivating the youth of Ann Arbor, Jeff teaches creative writing at both Pioneer High School and Eastern Michigan University. He also serves as the Literary Arts Director at Ann Arbor’s teen center, The Neutral Zone. As pioneer students of “Mr. Kass,” we had the privilege of conversing with him across wooden school desks in early March. We now sometimes call him Jeff. We hope that despite his assertion otherwise, his humility and humor will persuade you, like us, to conclude he’s the “coolest kid” you know.

Interview:

Carlina: All the knuckleheads in your book are very male, and the collection talks a lot about masculinity. We were wondering if women can be knuckleheads.

Jeff Kass: Women can definitely be knuckleheads. I think knuckleheads at some point should be a gender-neutral term, because to me a knucklehead is somebody who makes a lot of mistakes but still wants to do better, wants redemption, and wants to figure things out. There’s no reason why a female can’t be a knucklehead. You guys are a bunch of knuckleheads. [Laughter.] The mistake would be to think that a female knucklehead would be the same as a male knucklehead, in terms of making the same mistakes. Is it somebody who screws up relationships? Or sees the opposite sex in really stereotypical ways? Or cares more about lifting weights than paying attention to their mother? No, that wouldn’t be what a female knucklehead would do. Female knuckleheadedness doesn’t mean becoming a male knucklehead. There’s probably a whole female genre of knuckleheaded activities, but I just don’t know what they are.

Jeff Kass: Women can definitely be knuckleheads. I think knuckleheads at some point should be a gender-neutral term, because to me a knucklehead is somebody who makes a lot of mistakes but still wants to do better, wants redemption, and wants to figure things out. There’s no reason why a female can’t be a knucklehead. You guys are a bunch of knuckleheads. [Laughter.] The mistake would be to think that a female knucklehead would be the same as a male knucklehead, in terms of making the same mistakes. Is it somebody who screws up relationships? Or sees the opposite sex in really stereotypical ways? Or cares more about lifting weights than paying attention to their mother? No, that wouldn’t be what a female knucklehead would do. Female knuckleheadedness doesn’t mean becoming a male knucklehead. There’s probably a whole female genre of knuckleheaded activities, but I just don’t know what they are.

Carlina: What do you think the biggest difference is between males and females?

I can’t really claim to be a gender expert. But from what I see as a teacher, I think females are certainly less guarded than males. Males are often real hesitant to let anyone see that they are struggling with something, or that they really are passionate about something. That is just so rare. It’s no coincidence why we have so many females that do well in the poetry slams; females are more willing to take emotional risks in public than males are, right? And maybe females self-analyze more and are more willing to admit that they do, while males are self-critical but don’t want to admit that they are. Sadly, we are also seeing females being more successful, more ambitious as students, and they know what they want to do with their lives more than males. I don’t know if that is a new trend, or if that is just a result of years of concentrating on trying to make females understand that opportunities are available to them, and trying to help them feel like they can do whatever they want, and not necessarily devoting that same energy to males.

Carlina: Adding to what you just said, we thought of the book as an exploration of masculinity in a way, and wonder why you think that this exploration is necessary.

I think because I want boys to explore it more themselves. I think on some level it’s almost like asking white people to examine “whiteness,” which we don’t do enough. I think that in terms of race, we are always wondering what things are like for people of color; but it is also very important for white people to understand what it means to be white. And I think for males, it’s also important for them to understand what it means to be male. What are the various stages of growth in manhood? What are the various places along a spectrum where masculinity resides? Can you exhibit in your own life aspects—or different elements—of male-ness? I think that those are very important questions.

I’ve said this many times: It is very discouraging to me when I ask young males in my classroom, “What are you reading?” or “What do you like to read?” and they say, “I don’t read” or “I haven’t read a book since Harry Potter.” I think it’s sad. And I think if you look at most of the book-buying public, and what bookstores and what publishers want, they’re aiming towards the female population because females buy the most books. I think it’s important that we have males reading because I think reading is how we develop empathy. We can’t give up on males! [Laughter.] Even though I want the book to be read by everybody, part of me just wants every dang male from sixteen to twenty-five to pick up this book and read it—to see if they see themselves in these stories, and if they don’t see themselves, to know why they don’t.

Allison: One of your students said that he was honored and flattered that you (a teacher) would write a book for him. He seemed really happy about that! What do you expect your female readers to get from it?

That’s a really interesting response from a student. Part of me feels like I shouldn’t be telling people that this is a book for boys, or is directed towards them, because I feel like that is the number one way to make them not want to read it. [Laughter.] But I guess some part of me was hoping a kid would feel that way, like, “Oh, these stories are for me?” Ultimately, it’s an artificial distinction—it’s not about men or women but the human experience. As a writer, I want my literature to speak to everyone. So, you know, females in my class, I’m not ignoring you. But the reality is, I’m a male. And I want the males in my classroom to do better. I think my next book, hopefully, has more female characters that are more important and that play more important roles. Maybe that would be more helpful. I’m not trying to turn anyone off—it’s just that in my classroom, females are already doing so well.

Carlina: In terms of the written word and literature, where do you think that’s going to go in the future?

Wow. Great question. Common wisdom seems to say that stories are always going to matter, and that it’s just going to be the medium that’s different. That ten to fifteen years from now you may not be able to write a book that exists in book form, but that people will still be reading them on their iPad or iPhone. And that while the publishing industry might change, your task as a writer will still be the same. I’m not wholly convinced that that’s true…that my role as a writer won’t change with the mediums. And that’s sad to me. Watching a movie can be really powerful in lots of ways, but it’s not the same as reading a book. I think it’s important for people to spend time by themselves, to engage in ideas and stories.

But we’re moving toward a time where technology is creating for us a lot of experiences that are so much more interactive in terms of visuals and sound, whether that means 3-D movies or video game immersion experiences. So I don’t know what storytelling will look like twenty-some years from now. I think that it’s very possible that the written word, as we know it, could completely disappear. And I think that would be tragic. I’m doing everything I can for that not to happen. I hope that one of the really important things we’re doing at the Neutral Zone is creating new literature for young people that still has that same old technology, where the book is the focus.

Carlina: Your book is going to be an e-book/Kindle thing. How do you feel about that?

I feel good about that. I’m not necessarily opposed to the Kindle or the e-book. I love books—I love the smell of books, and all my shelves at home are filled with books—but I don’t have a problem with the experience of reading a book on a Kindle or e-reader or iPad. If that’s how the stories get to people, then that’s great.

I become a little more concerned when you consider what e-readers can do. For example, with a story that I’ve written…there’s suddenly a link to some wrestling match somewhere, so a kid is reading the story, then clicks on that link, then comes back to the story ten minutes later. Or if there is a reference to a song, then they can click on the link and listen to the song while they’re reading the story. I think that changes the experience of reading; and it feels to me that the piece of art that I’ve created becomes something else. So I’m not necessarily opposed to it, but that scares me more than just the idea of an e-reader itself.

I become a little more concerned when you consider what e-readers can do. For example, with a story that I’ve written…there’s suddenly a link to some wrestling match somewhere, so a kid is reading the story, then clicks on that link, then comes back to the story ten minutes later. Or if there is a reference to a song, then they can click on the link and listen to the song while they’re reading the story. I think that changes the experience of reading; and it feels to me that the piece of art that I’ve created becomes something else. So I’m not necessarily opposed to it, but that scares me more than just the idea of an e-reader itself.

Allison: Is there any song or visual piece of art that has encouraged or inspired your work?

Yes, yes, definitely. The kind of music that I listened to growing up was a mix of rock & roll that had really interesting lyrics plus poetic content. I’m not into the whole car thing as much as he is, but I think there is a lot that I take from Springsteen. There is a lyric in “Jungleland”: “The kids out here are just like shadows, always quiet, holding hands.” I think, “Why? Why are kids like shadows?  Why are they quiet and holding hands?” There is a sense of wanting some connection there, feeling less than substantial, like they don’t know where they fit in. My characters are like that, too—they don’t know where they fit in and they want some kind of connection, but there’s also a sweetness to them, that they want to hold hands; they want to do that, but they don’t know how. That was a big influence.

Why are they quiet and holding hands?” There is a sense of wanting some connection there, feeling less than substantial, like they don’t know where they fit in. My characters are like that, too—they don’t know where they fit in and they want some kind of connection, but there’s also a sweetness to them, that they want to hold hands; they want to do that, but they don’t know how. That was a big influence.

I also grew up with the very beginnings of hip-hop— Run-DMC, LL Cool J—and feeling the energy of all that. Hip-hop, to me, is a lot about claiming a voice, about looking at the culture around you and re-sampling it. You know, like DJs? And I think there are characters in this book who want that—they want to create a new sample of what they see and or who they understand themselves as.

Allison: What lesson would you most like to learn that your characters struggle with in the stories?

I think the process of writing Knuckleheads is, in some way, me forgiving myself for all of the knuckleheaded things I did when I was younger. For me to look back and say, “Yeah, you know, you did some dumb things, stupid things, but you can forgive yourself. It doesn’t make you a horrible person now. You can still forgive yourself and get better and be somebody who’s more caring and more thoughtful and who doesn’t make the same mistakes.” And hopefully that’s what the book will allow readers to do. The important thing is that we recognize our mistakes and not only learn from them, but also don’t necessarily feel that a mistake we’ve made brands us irredeemable, disastrous, hopeless. It’s more like, “You’ve made some mistakes. Now what are you going to do?”

Carlina: When was the first instance you felt really good about your writing?

The first poem I ever wrote for public consumption was for the sports radio station. I used to write something called the daily baseball report—I was the producer. A sort of baseball update for a host to read for the Seattle sports radio station; just about three or four minutes about what was happening in the world of baseball those days. And I wrote a parody poem about David Ekkers. So the host read this poem over the air and he really enjoyed it and we got calls in from people. That was the first affirmation—the first time my writing actually reached people.

I wish it wasn’t like that—I wish you could self-validate. But when somebody tells you “This is great,” it does feed you to want to try more and try harder because you think, “Well, somebody might actually read this someday.” It’s sad that sometimes you need [poetry] slam scores and things to validate you, but it boosts your confidence, and I think so much of writing is confidence—believing in your words, that somebody will want to read them, so you just keep at it.

I wish it wasn’t like that—I wish you could self-validate. But when somebody tells you “This is great,” it does feed you to want to try more and try harder because you think, “Well, somebody might actually read this someday.” It’s sad that sometimes you need [poetry] slam scores and things to validate you, but it boosts your confidence, and I think so much of writing is confidence—believing in your words, that somebody will want to read them, so you just keep at it.

Carlina: What else do you think somebody needs in order to be an effective writer?

I think you need to have confidence, but you also need to have the desire—you need to want to do it. Not everybody wants to do it. Some of that can be awakened, but desire’s a big part of it.

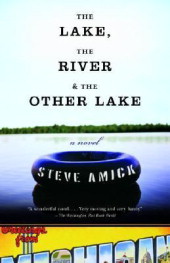

You need discipline. I think there are a lot of people who want to write, who love the idea of writing, but who never get through the hard parts. Sometimes it comes real easy and that’s great. But a lot of the time, it doesn’t. And I think you just have to be patient and dedicated and you’ve got to trust yourself to spend time alone. You’ve got to be able to be alone, in a room, where it’s just you and that page. You’ve got to be determined. Steve Amick, who’s one of my favorite writers, is manic. He told me he wrote two hundred pages of his novel The Lake, The River and The Other Lake in ten days. I love that story. Imagine him just sitting down writing days in a row. You’ve got to be willing to spend time with yourself. Discipline. Desire. And a sense of playfulness with ideas, words, and being able to imagine things and cook things up.

You need discipline. I think there are a lot of people who want to write, who love the idea of writing, but who never get through the hard parts. Sometimes it comes real easy and that’s great. But a lot of the time, it doesn’t. And I think you just have to be patient and dedicated and you’ve got to trust yourself to spend time alone. You’ve got to be able to be alone, in a room, where it’s just you and that page. You’ve got to be determined. Steve Amick, who’s one of my favorite writers, is manic. He told me he wrote two hundred pages of his novel The Lake, The River and The Other Lake in ten days. I love that story. Imagine him just sitting down writing days in a row. You’ve got to be willing to spend time with yourself. Discipline. Desire. And a sense of playfulness with ideas, words, and being able to imagine things and cook things up.

Allison: Along the line of playfulness, one thing I really appreciate about your stories, and you in general, is your “riskiness.” Like, you’re definitely taking risks. I feel like you’re never sure you’re the cool kid.

I’m always sure I’m not the cool kid. [Laughter.]

Allison: But what do you think inspires this “riskiness” in your writing? Where does that come from?

I think maybe what you’re talking about is something that comes more from poetry. In poetry, you can take leaps, and the transitions don’t always have to be clear. And if in your mind something is connected, you can create that impression for a reader or an audience, and there doesn’t always have to be a logical next step. I think that intrudes in the way that I write stories too. I’m interested in different elements that may or may not feel like they should be there.

I guess that’s playful. I don’t know. A story to me is not going to be fun for anyone else if it’s not fun for me, right? I have this weird sense of humor that people often don’t get, so I think my stories are like that, too.

Carlina: When we last talked, we spoke about writers who influence your work in a way. You mentioned Junot Díaz…

Yeah, Junot’s funny, too. And Junot’s funnier in person. Junot will make a room full of 7,000 people laugh and I don’t think I could do that. And I think his writing is funny, too.

Carlina: You also mentioned Julie Orringer.

Yes, Julie Orringer. I’ll say that these writers—Junot Díaz and Julie Orringer—have had a huge influence on my writing of fiction. Junot, because he gives me permission to say anything. Also, he doesn’t use the word “knucklehead,” but I get the sense that he also looks at male characters in this way. You know, like, “Wow, you just did something absolutely freakin’ ridiculous! What is wrong with you?” He comments on his own characters in that way, but at the same time never paints them as terrible people. Especially his own character, Yunior, who’s sort of like an alter ego. He’s just such a screw up! What a ridiculous person this guy is, you know? But at the same time, it’s not like there’s no hope for this guy. I learned a lot of that from Junot.

The other thing that Junot does is to defy convention in terms of how people act, and how they’re going to present themselves on the page. Junot will have a character who’s a total nerd, who loves science fiction books and comic books, and who is the kind of kid who never gets out of his house. Yet this same kid is pulling women left and right and treating them awfully. That’s just not a character that you would expect. That’s the other thing I get from Junot: the sense that characters can do all kinds of crazy things and have multiple contradictions, and that that can be okay, because they don’t have to conform to any stereotype. That’s a lesson that he really brings home to me, although I don’t think my characters are nearly as complex. But I think that’s something that I understand from him, and hopefully as my writing continues to grow I’ll be able to bring out a little bit more also.

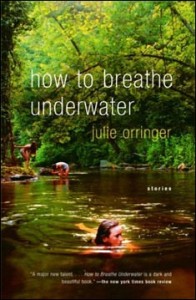

As for Julie Orringer, if I could think in some way of the female counterpart to Knuckleheads, her book How to Breathe Underwater might be it. She’s a much better writer than I am, but she’s got some coming-of-age stories of girls that might be the thing that female knuckleheads go through.

As for Julie Orringer, if I could think in some way of the female counterpart to Knuckleheads, her book How to Breathe Underwater might be it. She’s a much better writer than I am, but she’s got some coming-of-age stories of girls that might be the thing that female knuckleheads go through.

Julie is from Ann Arbor and she taught at the University of Michigan for a while. While she was here, I was really lucky to have her come into my class to teach a workshop. She was talking about using incidents from your own life but throwing ”What if” questions in there. So here you are, and you go to a football game with a girl, and it’s great, and you’re having fun, but what if you got drunk and threw up all over her? That didn’t happen in your real life, but in your story, it can. That’s the kind of thing that I think Julie Orringer allowed me to think about.

Carlina: So what was the process of sculpting all the characters in Knuckleheads? Are they alter egos?

I was just thinking about that today, because I’m doing a reading in New York, where a lot of the people that I grew up with are going to come. Especially with the stories like “Basements,” “Danny Rotten,” “Don’t Mess,” I think they’re going to recognize some of these instances. And I was putting myself in their eyes for a second and thinking, “Who does Jeff think he is in these stories?” I think that all of the characters probably have some elements of me in them, but none of the characters are fully me. So I was looking at “Basements,” for instance, and I was like, “Okay, in this part of the story where Dave is hitting the balls in the basement into the net, that feels like me. But the guy whose father died, which is also him, no, that’s not me.” And I think, obviously, in “Parent-Teacher Conference,” I’m sort of identifying with the teacher. But that teacher’s not really me either. And in “Don’t Mess,” I’m sort of identifying with the wrestler, who’s got blood in his mouth, but … is that really an alter ego of me? I don’t know. That guy seems a little more vicious and probably a better wrestler than I was. So, yeah, I think a lot of the characters have pieces of me, but there are some that have fewer pieces of me than others.

Allison: Speaking of “Basements,” that story stands out structurally in the collection. Is there anything special you were going for with that one?

That story is definitely different in its structure because it has a bunch of stories within a story – kind of a collage mix. And that story doesn’t really have a beginning, middle, and end in the way that you’d imagine a typical story arc. Although the pool-hopping part of it almost has its own arc. But I’m okay with traditional arcs. I think there is a movement in a lot of contemporary short story writing that’s trying in an experimental way to tell a story, and I don’t necessarily feel a need for that. In some ways I think that when you mess around with the structure too much to the point where it calls attention to itself and it’s clear that you’re trying to do something clever or different or interesting or experimental, it loses the magic of losing yourself in the story as a reader. So I haven’t necessarily had a huge desire to go out there and try a whole bunch of story structures or invent new ones. A story that’s well told appeals to me. I don’t think that has to be a lot of bells and whistles and strange ways of approaching it.

Carlina: It’s really profound how you’re able to listen so well to one piece of writing in class and have so much feedback. Did listening play a big role in writing Knuckleheads, if at all?

Yeah, absolutely. There’s no doubt that the fifteen years that I’ve been teaching creative writing to people your age, and learning how to listen better, has made me a better writer. Exponentially better. And it helps me listen better to my own stories and to care about them. At some level, I want no credit for being able to listen carefully to what students are writing, because that’s my job. That’s what I’m supposed to do. A doctor’s supposed to heal people. I’m a creative writing teacher, so I’m supposed to pay attention to y’all. I don’t want to give myself credit for that–that’s what I should be doing, that’s what I get paid to do. I choose to do this job. But I will say that it’s hard. And I understand why teachers sometimes tune out. Even I find myself tuning out sometimes. It’s not an easy thing. You guys see me do it for one period. But you’ve got to understand that I have three periods in a row –

Allison: For like, ten, fifteen years?

Well, yeah. Maybe there is a cumulative effect. But sometimes I’m teaching at night too. There have been days where I’ve done that for maybe five, even six periods. And that’s hard for maintaining focus and concentration. And I’d be lying if I said, “Oh, yeah! But I still figured out a way to do it!” However, if a writer shows me a lot of effort, then I’m going to show a lot of effort. And if somebody writes something that I can tell they did not put a lot of time into, then they’re probably not getting my best listening, either.

But in terms of helping me as a writer, it’s hard for me to think of a bigger factor than this— there’s something about hearing the rhythms of your language, hearing your concerns, that I’m sure helps me develop characters that feel believable as high school students, or feel believable in terms of what they’re going through as a young person. So I don’t think there’s any doubt that that happens. And I know it because I read other stories by young adult writers or writers who are creating teenage characters and I’m like, “Pfffft—no chance. You got it wrong. That’s condescending. That’s not how teenagers are going to be.” And I feel like I get an advantage because I’m amongst you guys, and that helps me understand what you go through and so hopefully I can write stories that speak to that in a believable way and will reach out to you. So, yeah, I think that’s a huge part of what helps me write.

Carlina: Do you think you’ll ever be at a point in your writing career where you become either bored or completely fulfilled by writing?

I definitely hope not. No, I don’t think so. I have all these ideas. Like, “Oh, yeah! I want to write that story! I want to write about that minor league baseball player who doesn’t make it; I want to write the story about the sports talk show host; I want to write about the murder mystery.” I don’t think I’m going to get tired of writing, because I enjoy it so much. I just enjoy the process – the in-the-zone feeling.

One thing I worry about: I see writers who I adore get some measure of success, some critical acclaim, or they get a teaching position somewhere in some prestigious university, and then their second novel [shaking his head]…it seems like they lost that thing that made them fresh or interesting in their first book. That I really loved. Sometimes the second book is still okay, sometimes it’s still pretty good, but it almost feels like if you get accepted by the Academy, if you get accepted by the literary world, then sometimes there’s a tendency to just say, “Well, now I’m a part of it. I’m not an outsider anymore trying to break into something new.” And I always want to be the damn outsider.

Are some people going to like this book? I hope so. Are some people going to think this guy really isn’t a great writer? “What is he writing about these kids for? It’s a juvenile topic.” And I’m like, “Damn, right!” I’m writing books that, hopefully, that kid in my class who hides in a sweatshirt all day is going to read. That’s who I want to read it. I don’t really care that much what the big-time professor or literary critic has to say. And part of me wants to keep that attitude. I never want to feel like my work has been accepted, I always want to push myself to do it better, to try to still stay true to who I am and to not fall into any kind of conventional pattern.

Are some people going to like this book? I hope so. Are some people going to think this guy really isn’t a great writer? “What is he writing about these kids for? It’s a juvenile topic.” And I’m like, “Damn, right!” I’m writing books that, hopefully, that kid in my class who hides in a sweatshirt all day is going to read. That’s who I want to read it. I don’t really care that much what the big-time professor or literary critic has to say. And part of me wants to keep that attitude. I never want to feel like my work has been accepted, I always want to push myself to do it better, to try to still stay true to who I am and to not fall into any kind of conventional pattern.

And I don’t really consider myself experimental; I think at heart my stuff is pretty traditional. But in a way there’s something radical about that, too, because I’m not trying to necessarily fit a contemporary trend. I’m trying to do what I want to do as a writer, and hopefully that’ll work. And I don’t know if it will, but I don’t ever want to not be that. I always want to be that Jew Troll guy that nobody likes who always has to battle for something –

Allison: The New Kid?

Even if it’s not true anymore, I like being that scrappy person who’s only going to get by through desire and heart and discipline. I don’t really want to be that person who gets by on reputation. I never want to be that. As a teacher, as a writer, anything. So that’s what I fear more than if I’m going to tire of writing.

Carlina: So when you started writing the stories, did you intend to have a collection of people who were all knuckleheads?

No. I definitely did not write all these stories thinking, “Let me create a collection of knucklehead stories!” Definitely not. I mean, yeah, I did have the idea of writing stories that I thought would speak to a population that a lot of literature wasn’t necessarily speaking to. I did think about that. But that wasn’t all my stories. Some of the ones that didn’t get into the collection are the ones that maybe don’t quite fit that theme. When I tried to think, “What is this collection called? What is the unifying theme?” it became clear to me that we’re looking at a lot of characters who are making a lot of mistakes but who we don’t want to give up on yet, not completely. And that term “knucklehead” was really conscious in my mind. I thought about calling it Life of Knuckleheads or Knucklehead Chronicles. But eventually I was just like, “Knuckleheads. That’s what this is. This is a collection of knuckleheads; this is what I have to offer.”

Carlina: On the spectrum of knuckleheadness, where do you think you are?

I’m still a pretty severe knucklehead. The fact that I can recognize this probably makes me slightly less knuckleheaded than I used to be. I’ve always liked those teachers or those authors who, when I see them speak, have said something like, “There’s so much more left for me to learn.” That’s a really enlightening thing to say. And as a knucklehead, there’s so much more growth left for me to do. But the fact that I realize that probably means I’m slightly less knuckleheaded than I once was. Certainly my relationship with [my wife] Karen, growing older, being a teacher, seeing my students every day, helps me be less knuckleheaded.

But I always want to be a little bit of a knucklehead, because that means that there’s always something that I can get better at. And I also think that it gives hope to other people, to say, “I don’t ever want to say that I’m perfect. I’m not! I’m a knucklehead still. I make mistakes. And you know what? You’re always going to be a knucklehead, too, and that doesn’t mean that you can’t do a lot of good in your life. So it’s all right.”

I’m a knucklehead. I claim that proudly, if a bit shamefacedly. But you know, I’m alright with being a knucklehead because if for some reason I thought I wasn’t a knucklehead, then there’d be something that I wouldn’t like about me.

Guest Contributors:

Carlina Duan is currently a senior at Pioneer High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She will be attending the University of Michigan next year, where she hopes to pursue a career in teaching English literature and Creative Writing. Carlina manages her life as both editor of the school newspaper and older sister with multi-colored post-it notes spattered across her continually full planner. A member of this year’s Ann Arbor Youth Poetry Slam team, Carlina will be traveling to San Francisco this summer to participate in the Brave New Voices Slam Festival.

Carlina Duan is currently a senior at Pioneer High School in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She will be attending the University of Michigan next year, where she hopes to pursue a career in teaching English literature and Creative Writing. Carlina manages her life as both editor of the school newspaper and older sister with multi-colored post-it notes spattered across her continually full planner. A member of this year’s Ann Arbor Youth Poetry Slam team, Carlina will be traveling to San Francisco this summer to participate in the Brave New Voices Slam Festival.

Allison Kennedy lives in Ann Arbor feeding off of the wondrous writing opportunities that the Neutral Zone and University of Michigan provide. She is pursuing her education at Hunter College in Manhattan this coming fall, and though she has never been to New York City, she is still excited. Allison spends a large percentage of her time sending her sisters postcards, watering tropical plants at her job and forcing anyone within twenty feet to read poems by Patrick Rosal, Angel Nafis and Jeffrey McDaniel. Her favorite novels include White Teeth by Zadie Smith, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer and Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates.

Allison Kennedy lives in Ann Arbor feeding off of the wondrous writing opportunities that the Neutral Zone and University of Michigan provide. She is pursuing her education at Hunter College in Manhattan this coming fall, and though she has never been to New York City, she is still excited. Allison spends a large percentage of her time sending her sisters postcards, watering tropical plants at her job and forcing anyone within twenty feet to read poems by Patrick Rosal, Angel Nafis and Jeffrey McDaniel. Her favorite novels include White Teeth by Zadie Smith, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer and Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates.

BONUS TRACK:

Allison: So what do you find beautiful?

What do I find beautiful? Wow, good question. Let’s see.

Allison: GO DEEP!

Besides Karen? Sam and Julius? Alright, so things that I think are beautiful – I’m just gonna make a off-the-top-of-my-dome list poem for you okay?

Allison: Ahhh, the best!

Water in the ocean when you can’t see anything else except for water, baseball diamonds with people running around on them and wearing sweatshirts and baggy sweatpants, fresh-baked pizza outta the oven, when students are really really helpful to each other, especially when they reach out to each other in ways that I just don’t expect, they help somebody with an idea for a poem and it’s the right thing to say, or they offer somebody a ride home who didn’t expect that was gonna happen. I love it when I see the humanity of students toward each other, and they break out of the – “this is high school & let’s play our roles” thing, when they get past that, I think that’s really really beautiful. I think it’s beautiful when you guys write, and you write well, and you try so hard in reading your work in front of other people and I think it’s so ugly when the judges put numbers on it, but I think it’s really beautiful that you guys are willing to take that risk, and do it anyway, and stand up in front of that microphone and be totally nervous, I think that’s really, really incredibly extraordinarily beautiful. I love sunrises in the morning over the pioneer parking lot, when you get here at 7am and it’s freezing and people are trudging to school and the sky looks so beautiful. I love the end of the school day when I’m so exhausted I can hardly walk, I think that’s really beautiful. And..I love the way sunlight looks through trees that are full of leaves. It’s kinda like this kaleidoscope of sun and tree and sky and I think that’s really beautiful, and…

Allison: YOU’RE GOOD!

Is that enough?

Allison: YEAH, I think we’ve established that you’re “DEEP!”

[Laughter.]

Further Links & Resources:

– June 22-23: The Creative Writing Institute for Teachers. click the link for more information or to register.

– June 24-26: Girls Rock.

From the NZ website: Spend three awesome days jamming with other girl musicians, networking with women who are making careers in the male dominated music industry, learning about gear, running a band, and DIY promotions. Each day will include a lunchtime performance by one of our guest artists (ladies only!), workshops and a jam session.– June 26- July 1: The Volume Summer Institute For Writers.

From the NZ website: This nationally acclaimed weeklong workshop puts teens’ interests in developing skills as writers together with nationally and locally recognized performance poets, prose writers and hip hop artists in a relaxed and encouraging environment. Participants will have an opportunity to take part in daily workshops taught by talented and dedicated instructors in poetry, short fiction, creative non fiction/college essay, or hip hop writing/mc-ing. All experience levels welcome.– June 27 – July 2: Beginning Photography.

From the NZ website: Learn the fundamental principles of photography such as composition, value, color, portraiture, nature photography, and abstraction. Hike to fascinating photographic destinations, take tons of photographs, and return to NZ for group critiques. Bring your own camera or we have plenty to share.

From the website:

Red Beard Press is an independent, youth-driven publishing company dedicated to creating cutting-edge literary arts projects, publishing emerging voices, and inspiring passionate literary communities. Call us idealistic, but we believe in the power of the written word. We believe young people still love to read. We firmly defy the suggestion that coming generations won’t embrace the same love for language and literature that fed previous ones. We aim to be a publishing project that treats young people not as consumers to be sold to, or as chunks of clay to be molded and manipulated, but as active, vibrant minds that itch to be engaged. We want to create books that young people carry everywhere in their backpacks and back-pockets.