“Dear Frozen Peas Manufacturer”—how else would Lydia Davis’s short story “Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer” begin? But following this salutation we soon stray from the expected. “We are writing to you,” the letter-writer writes, “because we feel that the peas illustrated on your package of frozen peas are a most unattractive color.” The letter goes on to point out that the peas on the bag are “a dull yellow green… nothing like the actual color of your peas, which are a nice bright dark green.” Plus the color of the depicted peas—which, by the way, are also too big—clashes with the color of the lettering. “You are falsely representing your peas as less attractive than they actually are.” Strange complaint! “We enjoy your peas and do not want your business to suffer,” the letter concludes. “Please reconsider your art.”

“Dear Frozen Peas Manufacturer”—how else would Lydia Davis’s short story “Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer” begin? But following this salutation we soon stray from the expected. “We are writing to you,” the letter-writer writes, “because we feel that the peas illustrated on your package of frozen peas are a most unattractive color.” The letter goes on to point out that the peas on the bag are “a dull yellow green… nothing like the actual color of your peas, which are a nice bright dark green.” Plus the color of the depicted peas—which, by the way, are also too big—clashes with the color of the lettering. “You are falsely representing your peas as less attractive than they actually are.” Strange complaint! “We enjoy your peas and do not want your business to suffer,” the letter concludes. “Please reconsider your art.”

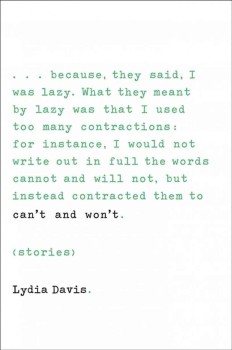

“Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer” is only the first of six wonderful “Letter” stories in Davis’s Can’t and Won’t, published just this April by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In “Letter to a Peppermint Candy Company,” the letter-writer—Davis leaves all (or almost all) the letters anonymous—asks the maker of “Old Fashioned Chewy Peps” to “please explain” the “discrepancy” between the advertised and actual number of candies in the company’s very expensive “can (or tin)” of peppermints. The subject of “Letter to a Hotel Manager” is the misspelling of the word “scrod” as “schrod” on the menu of a Boston hotel restaurant. “I do believe the purported home of the scrod should be a place where it is spelled correctly,” the letter-writer writes on the fifth and final page of the letter. “Thank you for your attention.”

If you’ve read Lydia Davis’s work, then you’ve laughed at her quirky, understated sense of humor. And the “Letter” form is a perfect home for what James Wood calls Davis’s “sly comedy,” accommodating as it does the distortion of minor, mundane details into centers of obsession. Because as letters, these stories call extra attention to themselves as constructed or written—so that for these writer-narrators, details like the possibly German accent of the hotel restaurant manager (which could, she speculates, account for the “very Germanic ‘sch’ spelling” of the unpalatable “schrod”) move far beyond passing observations: they have been noted, yes, but then ruminated on and recast into words, sentences, and paragraphs for comprehension by a specific audience. “We have compared your depiction of peas to that of other frozen peas packages,” the letter-writer writes, “and yours is by far the least appealing.”

But where there’s comedy there’s tragedy, too—what Wood terms Davis’s “metaphysical bleakness.” While some of the “Letter” stories lean more toward comedy (“Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer”), in others Davis tempers her lightness with darkness in a captivating act of balance. For example “Letter to a Marketing Manager,” in which the author of a recently published book writes to clear up a Harvard Book Store newsletter error which misidentified her as a former patient of McLean psychiatric hospital. In her muted desperation she offers potential explanations for the mistake, including, finally, her “admittedly somewhat wild-eyed photograph.”

But where there’s comedy there’s tragedy, too—what Wood terms Davis’s “metaphysical bleakness.” While some of the “Letter” stories lean more toward comedy (“Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer”), in others Davis tempers her lightness with darkness in a captivating act of balance. For example “Letter to a Marketing Manager,” in which the author of a recently published book writes to clear up a Harvard Book Store newsletter error which misidentified her as a former patient of McLean psychiatric hospital. In her muted desperation she offers potential explanations for the mistake, including, finally, her “admittedly somewhat wild-eyed photograph.”

Still, for the most devastating “metaphysical bleakness” see “The Letter to the Foundation,” a thirty-page excursion into the life and mind of a professor who finds teaching “crushing and almost debilitating” and who is writing years after receiving a prestigious grant from the Foundation—a grant she’d hoped would relieve her of her teaching obligations, but didn’t. The letter-writer is at her bleakest when she describes the moment she first thought “clearly about all the scenes that took place when I wasn’t there to witness them.” She goes on, descending toward rock-bottom:

And then, I had a stranger and less pleasant thought: not only was I not necessary to those scenes, and not necessary to those lives that continued to go on without me, but in fact, I was not necessary at all. I didn’t have to exist.

I hope you understand how that is related.

Whether this revelation should actually mean existential despair or unburdening, it points to what may be at the heart of the “Letter” stories collectively. The more of these stories we read, the more we get the sense that what’s as important to these characters as having their questions answered or their advice taken is simply reaching out from a place of unbearable aloneness to make a connection. Davis’s first-person stories often read as monologues; the one-sidedness of the “Letter” stories—there are no responses, within the compass of Can’t and Won’t or, we understand, outside it—only amplifies this feeling of solitude. And since we never see a connection made, perhaps even more important to the letter-writers is the sense of purpose and meaning that comes from the act of writing itself. “You will barely remember me,” the letter-writer writes to the Foundation, “even when you consult your files.” But the “Letters” resist, in their own quiet way, the threat of nonexistence. They assert that someone—“Yours sincerely”—is there.

And by the end of the six “Letter” stories, we do care about that “someone.” It could be Lydia Davis herself. “Letter to the President of the American Biographical Institute, Inc.” ends the series on what might be considered an optimistic or triumphant note. In this “Letter,” the letter-writer has been notified that she is being recognized as “WOMAN OF THE YEAR” by the Institute. But we know she knows it’s a false recognition of her existence—she knows it’s a scam. They’ve even addressed their notice “not to Lydia Davis, which is my name, but to Lydia Danj.” I love how Davis wins revenge via her letter’s passive-aggressive takedown of the Institution’s careless, exploitative methods, which prey on the same basic desire for acknowledgment we’ve seen at work throughout the “Letter” stories. She goes even further by having her “Letter to the President of the American Biographical Institute, Inc.” (the Institute’s as real as Lydia Davis is!) published for all to read in her smart, hilarious, and authentically praiseworthy new book. She finishes, sly as ever, with a challenge: “I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this.”