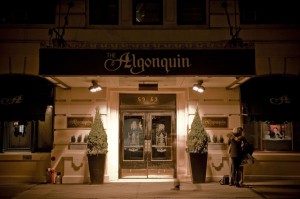

When I asked Janice Eidus where she’d like to meet for our interview, she responded with, “Well, I have an absolutely literary idea…” Which is how we wound up at the Algonquin Hotel, sipping tea on a perfect October afternoon, and pondering sex, death, feminism, and vampires. Dorothy Parker would have been proud.

Called “one of the freshest and most idiosyncratic voices from the fiction frontier” by the San Francisco Chronicle, Eidus, much like Parker herself, isn’t afraid to tackle the big issues with her own brand of wit, humor, and heart. A two-time O. Henry Prize winner, she is also the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, a Redbook Prize, and an Independent Publishers Award in Religion.

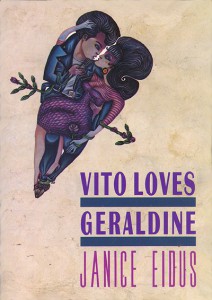

A novelist, short story writer and essayist, Eidus’s work spans genres and subjects, but she is particularly passionate about Jewish identity, contemporary culture, and women’s issues. Her previous publications include the novels The War of the Rosens, Urban Bliss, and Faithful Rebecca, as well as the short story collections The Celibacy Club and Vito Loves Geraldine. She is also widely published in anthologies, including Neurotica: Jewish Writers on Sex and The Oxford Book of Jewish Stories.

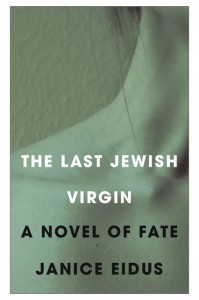

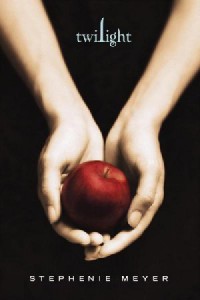

Eidus’s newest novel, The Last Jewish Virgin, was just published this month by Red Hen Press. NPR’s Marion Winik has called it “Twilight…with a sense of humor, a brain, and a feminist subtext.” So Twilight was where we began as we sat down to discuss Eidus’s novel, what it means to judge a book by its cover, and why vampires are people, too.

Interview

LAUREN HALL: I suppose we have to begin with the elephant in the room. There’s been a flood of supernatural fiction — both YA and adult — in the wake of Twilight’s success, which makes for a very crowded market. Were you at all concerned about finding an audience for The Last Jewish Virgin?

JANICE EIDUS: (Laughs.) You know, I have been obsessed with vampires since I was a little girl.

Really?

Yes. I have seen them be hot, and not hot, and in and out and cool and totally out of the mainstream, but my interest has never, never wavered. I think there will always been an audience for people who are interested in the vampire myth. And I think there are a number of things that contribute to it. One is that those of us who are obsessed with it and love it so much can’t get enough of seeing how people make it new. How do you reinvent it? How do you reinvent it for these times, for your vision? And for every schlocky thing that fails, there’s something brilliant and amazing. The myth is constantly being renewed, like the vampire itself is constantly being renewed.

Yes. I have seen them be hot, and not hot, and in and out and cool and totally out of the mainstream, but my interest has never, never wavered. I think there will always been an audience for people who are interested in the vampire myth. And I think there are a number of things that contribute to it. One is that those of us who are obsessed with it and love it so much can’t get enough of seeing how people make it new. How do you reinvent it? How do you reinvent it for these times, for your vision? And for every schlocky thing that fails, there’s something brilliant and amazing. The myth is constantly being renewed, like the vampire itself is constantly being renewed.

I also think there’s such a fascination at this particular point in time because one of the draws of the vampire myth is eternal life and eternal love. You don’t die and your beloved doesn’t die. We’re living post 9/11, in a terrible economic recession that does not seem to be ending, and every day we open the newspaper and there seems to be a new plague with no cure. There’s no rhyme or reason. You walk your child to school in the morning, you get on an airplane, you get on a bus, and you have no idea if you’re going to make it through the day. I think we’re being forced to confront our mortality all the time in new ways. And I think the vampire myth is oddly comforting to people.

Margot Adler, the NPR commentator, is obsessed with vampires, too, and she talks about another part of the vampire myth: she talks about power. Vampires have tremendous power over mortals, and they have to confront how they will use that power, which ultimately makes them very human. Because we’re constantly having to deal with ethical and moral issues. So, I feel that they’re really us. Vampires are us. I think there will always be an audience for Twilight, for me, for the next person.

Margot Adler, the NPR commentator, is obsessed with vampires, too, and she talks about another part of the vampire myth: she talks about power. Vampires have tremendous power over mortals, and they have to confront how they will use that power, which ultimately makes them very human. Because we’re constantly having to deal with ethical and moral issues. So, I feel that they’re really us. Vampires are us. I think there will always be an audience for Twilight, for me, for the next person.

At times, the pace of The Last Jewish Virgin feels more like a classic Gothic novel than contemporary fiction; the suspense builds in such a languid and sensual way. Did you draw inspiration from Gothic novels as you considered your writing process?

Absolutely. One of the great pleasures of working on this book was that I revisited much of my most beloved vampire literature and film. It’s been incredible to go back to books that I’ve loved so long. You know, people often compare Bram Stoker’s Dracula to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and say it’s the minor book, but for me, it’s equally major.

I really felt that I was reaching backward and reinterpreting, reinventing, paying homage, subverting it a little bit, tweaking it, having tremendous fun with it…but basically, in my heart, I pay tremendous honor.

You define the term bashert in the beginning of the book as Yiddish for “destiny,” usually used in the context of one’s Heavenly foreordained spouse or soulmate, which is the case in this story. But equally important is the relationship between the protagonist, Lilith, and her mother, Beth. In many ways, they’re also each other’s beloved. Was this a jumping off point for you in telling this story, or is it something that arose through your writing process?

It was totally a part of my process. In a way, the vampire myth became a catalyst for me to examine things that ranged from very theoretical to very, very personal to me. I adopted my daughter during a period when my own mother was very sick, so I was caretaking my mother as I was taking care of this new little baby, and dealing with things on both ends. My mother and I had always had a very conflicted relationship – there were ways in which we were incredibly alike, and ways in which we were not.

For me, one of the things that was so interesting was looking at Lilith and Beth and the ways in which they were alike that perhaps they didn’t even know how alike they were. They are each other’s beloved, and each one really needs to be heroic toward the other, to try to save the other.

Without giving anything away, the choice that Lilith makes in the end is just as much about saving her mother’s identity as it is about discovering her own.

You know, I think in many ways, this book is also the reinvention of the classic coming of age tale.

Exactly. Where a young person who’s an innocent really has to confront sex and death for the first time. And what is done with that, how identity is formed. Lilith is acutely aware of the fact that she’s forming her own identity. She’s forming it in opposition to her mother in a lot of ways, which a lot of young girls do.

The title is The Last Jewish Virgin. How important was it that she be a virgin?

Very important. And that was something I really had to wrestle with. She had to be a virgin because I really wanted to reengage with the classic vampire myth, where the male vampire needs the blood of young female virgins to survive. And I thought: I have to do that, I have to honor that, I don’t want to mess with that. But then what would her motivation be – this young, beautiful, intelligent woman living in Manhattan – to stay a virgin? And what worked perfectly in terms of who she is, is a young woman who is so obsessed with wanting to get ahead in her career that everything else strikes her as in the way. And that would include lust and love and sex. She believes, mistakenly, that those things are kind of sloppy emotions, which she associates with her feminist, idealistic mother. And she sees her mother’s idealism, which to me is kind of heroic, as naïve and old-fashioned.

Very important. And that was something I really had to wrestle with. She had to be a virgin because I really wanted to reengage with the classic vampire myth, where the male vampire needs the blood of young female virgins to survive. And I thought: I have to do that, I have to honor that, I don’t want to mess with that. But then what would her motivation be – this young, beautiful, intelligent woman living in Manhattan – to stay a virgin? And what worked perfectly in terms of who she is, is a young woman who is so obsessed with wanting to get ahead in her career that everything else strikes her as in the way. And that would include lust and love and sex. She believes, mistakenly, that those things are kind of sloppy emotions, which she associates with her feminist, idealistic mother. And she sees her mother’s idealism, which to me is kind of heroic, as naïve and old-fashioned.

You also write short story collections. How did you know The Last Jewish Virgin would be a novel rather than a short story?

With every novel that I’ve written, I’ve known almost from the moment I’ve started it that it had to be a novel and not a story. It’s a visual thing. It’s as if I start it, and I see a landscape. And if the landscape goes on and on and on, and I can see where it ends very far in the distance, I know this is a novel. And if it’s a story, I see a small landscape of some sort that’s very enclosed and very concrete. That really is my process, and I’ve never been wrong.

I’ll also say, retrospectively, that writing a story is like being in an incredibly intense love affair. Writing a novel is a committed, long marriage. You idealize it in the beginning, you get disillusioned, and then you have to find a way to get back and fall in love with it again now that you know its problems and foibles.

And sometimes you get divorced?

Oh, I’ve had that, too. I’ve had some novel divorces, I promise you. Sometimes I’ve even got as much as three quarters of the way through, before I knew this had to be a divorce.

How do you do that?

You just do it. You’re ruthless. I can be so ruthless about my own work.

You believe in killing your darlings.

I do. And part of it is this visual image again; the landscape starts to fade, and it’s not there for me anymore. Luckily, there haven’t been too many of these. I think maybe two novels that I started and really never finished. But the others I finished. Some of them you always know, you never waver, you know exactly where you’re going. Others, the process is really circuitous. But you still know there’s a place you’re going to that’s far off and that you need to reach.

I do. And part of it is this visual image again; the landscape starts to fade, and it’s not there for me anymore. Luckily, there haven’t been too many of these. I think maybe two novels that I started and really never finished. But the others I finished. Some of them you always know, you never waver, you know exactly where you’re going. Others, the process is really circuitous. But you still know there’s a place you’re going to that’s far off and that you need to reach.

Walk me through the months leading up to a first draft. How do you start?

Well, I’ll tell you exactly how this novel started. I was on a plane, and I started thinking about vampires, and I started making notes longhand about characters. So I had characters, but no plot. Again, this landscape started appearing to me, and I started just writing, stream of consciousness. And then the voice came to me. I knew whose voice I was telling it in, and I knew the voice was looking back. I knew this was someone looking back from a different place. And then it started to come to me. I remember at one point I had a beginning and an end and no middle. But I just kept writing. I really believe that people who compare writing to a Zen practice are right. Not that I practice Zen, I don’t, but I know what they mean. Really, it’s the practice. You just have to get there and write. I’m one of those writers who say, “If I had to wait for my muse every day to appear, I’d have written one poem in my entire life.” You know, you write when you don’t have the muse, you write in less than ideal physical circumstances, you just write.

Do you protect time every day to write?

I wish I could tell you that I do; that would be my ideal life. But, no. There are days when, you know, Parent/Teacher night, or getting my daughter her flu shot – which in New York becomes a Herculean task – mean that I absolutely can’t get to it. But I burn with the desire. I literally burn with the desire. I would go crazy if three days in a row went by where I couldn’t write. And that almost never happens.

We own a house in Mexico in the mountains of San Miguel de Allende, which is a beautiful, beautiful town. We go there a few times a year, and I always bring a computer with me, but I try not to use it. I feel so connected to the place and to its history, and I just work in longhand when I’m there. I sit for days and days and I write in longhand. I love it, because I slow down when I’m there – you can’t be in Mexico and not slow down. Also, I happen to love my own handwriting. It’s very big and loopy and swirly, and when I look at it, I feel inspired to go on.

Do you think a change of scenery for a writer plays into the way a particular story evolves?

I do. I really do. I won’t universalize it, but for me, and for many people I know, where we are finds its way in. Even if it’s just because you physically feel different. I love to be on the go when I’m writing. I cannot just sit home for hours and hours in solitude. I love writing in hotel bars. I love writing in cafes. I write on airplanes. I used to write on the subway, but that one I cannot do any longer. (laughs) I did for years, though. I love the stimulation of seeing people. For me, working in a hotel bar, I see the other people, I’m interested in the other people, but I’m also very alone. And that, I love. I mean, there’s nothing more disappointing than going to write somewhere and running into someone you know.

You are also a private writing teacher and coach. How do you respond to those who think writing cannot be taught?

I’ve been hearing that for years, and yet I love teaching writing! At the moment, I’m actually doing two kinds of teaching. I have my private writing clients, and I’m also teaching at a low residency MFA program at Carlow University. What I’ll say is that I can’t give someone a vision. I can’t give them the drive. But, when someone comes to me with a story, I feel that as a teacher, by talking to them and looking at their work, I can try to understand what it is they’re trying to say, what it is they’re trying to express, and help them learn how to express it better. Help them find their truest voice as a writer. I’ve met writing teachers over the years who’ve told me that they feel the best thing they can do is help their students write more like them. I am ideologically opposed to that. I think it’s the worst thing you can do. And the range of the students and clients that I have shows that.

I’ve been hearing that for years, and yet I love teaching writing! At the moment, I’m actually doing two kinds of teaching. I have my private writing clients, and I’m also teaching at a low residency MFA program at Carlow University. What I’ll say is that I can’t give someone a vision. I can’t give them the drive. But, when someone comes to me with a story, I feel that as a teacher, by talking to them and looking at their work, I can try to understand what it is they’re trying to say, what it is they’re trying to express, and help them learn how to express it better. Help them find their truest voice as a writer. I’ve met writing teachers over the years who’ve told me that they feel the best thing they can do is help their students write more like them. I am ideologically opposed to that. I think it’s the worst thing you can do. And the range of the students and clients that I have shows that.

Do you change your approach with someone who’s an emerging writer versus someone who’s more established?

I don’t change my approach; I go more slowly. I try to always be constructive, because, honestly, my experience is that no matter how widely published you are, no matter what age you are, you’re still really vulnerable. People are really vulnerable. And I am as honest and constructive with my students who have won awards as I am with the one who is coming to me for the first time.

I can often tell very quickly who isn’t going to stick with writing. And that usually will begin with someone who comes to me and says something like, “I’m 39 years old, and if I haven’t finished and published a novel by the time I’m 40, I’m not meant to be a writer.” And you know, if I can’t help them to see that by the time they’re 40 we might still be working on the same 50 pages, the frustration level gets too high, and that makes me sad.

Do you think it’s more an issue of talent or perseverance?

That’s such an interesting question. I think that without the perseverance, you can’t do anything. Years ago, I taught a private workshop in my apartment to three women writers. They had all sought me out, they were all friends, and they all wanted to work with me. They were great women, I would say they were equally talented, and only one of them stuck with it. And she’s gone on and done really, really well. But I couldn’t have told you when they first started which of the three women would do that. I was hoping it would be all three of them. But I believe the other two were just as happy not writing.

What’s a greater source of accomplishment: seeing your own work in print or helping a student see his or hers?

Well, when I see my students publish – there’s a Yiddish word, kvell – I really, really kvell. I’m probably harder on myself, but I’m certainly happy when I have a publication. I’ve never gotten over that happiness, whether it’s a book, a story, or a piece in an anthology. But there is a kind of maternal quality that I have toward my students, and I’m not so maternal toward myself.

Going back to your interest in the visual, I have your galley here, which of course is not how The Last Jewish Virgin will look when it’s published. How involved are you in what your book covers look like?

As a writer you never know how much input you’ll have, but in this case, the publisher came to me and asked me if I had any ideas for an image for the cover. They sent me some images, and they weren’t what I had in mind, so I then described and found some images for them. Ultimately, I was very happy with what they chose.

They say you can’t judge a book by its cover, but when you’re confronted by endless stacks at Barnes & Noble, you have to wonder how many times people just gravitate toward the images that speak to them.

They say title and visual, that’s what people are drawn to. I, in fact, have been thinking about writing an essay about that, so it’s very interesting that you’re asking. I’ve been thinking about writing about what it feels like as a writer to have input, what it feels like not to have input in your own cover. How a cover speaks for you or doesn’t speak for you.

What happens when one of your books comes out with cover art that you feel is not evocative of what’s inside?

I’ve had friends who have had that experience; they were really appalled by the cover. The hope is that gradually you will learn to live with it, but it’s hard to understand. I feel really lucky, because I have not once had a cover I didn’t ultimately love. I’ve had a lot of input in many of them, so in some ways it’s not a coincidence, but even in the ones where I didn’t have input, I’ve just really been lucky that way.

What’s next for you? Any new projects on the horizon?

I have two big projects on the horizon. I’m working on a Young Adult novel that I’m describing as Romeo & Juliet with a Jewish twist in Brooklyn. And I’m also going to be working on an anthology having to do with illness – healing from illness and living with illness and growing from illness and writing from illness.

That’s very topical right now.

Very, very topical right now. In my case, I was diagnosed as having celiac disease about ten or eleven years ago, but I’ve had it my whole life. It’s something that has really changed my life; it’s like another part-time job that I have to do. It’s been an interesting process, and I’m interested in talking with other writers and about it.

Do you consider yourself primarily a fiction writer? I know you write nonfiction as well.

All my books have been fiction, but I’ve written so many essays, and I’ve taught creative nonfiction so much that I guess I feel in my heart that I’m both now. I’ve been doing fiction longer, but I actually feel that they’re kind of evening out, and I like that. Fiction came much easier to me, I always had a quirky world view and I felt very playful with fiction. I had a harder time figuring out how to structure nonfiction so that it stayed interesting and I wasn’t just writing by the numbers. But now I would say absolutely that I can approach both of them with the same amount of ease.

In both genres you’re asking the same questions, it’s just the end result that differs, isn’t it? I mean, no one wants to read about a fictional character that doesn’t feel true to life.

Absolutely. Even a vampire has to be true to life.

I read a great quote from you in Bitch, where you said, “I think the reason there’s never been a Great American Novel written by a woman is that there have been, but they don’t tend to be about fishing or war.” I want to put that on a t-shirt. But beyond that, I’d love to hear about other women writers who inspire you.

Oh, there have been so many. I was just thinking this morning, going back to the idea of Gothic novels, about the British writer Sarah Waters. She’s a really interesting writer, and she is reinventing Gothic. I wait for every new book of hers to come out. I love Margaret Atwood. I really love her work, and I love that you never know what she’s going to do. She’s honest, passionate, and authentic no matter what she does. And she’s prolific, but at no expense to the quality of her work. I really admire her. I love Edwidge Danticat. She’s a Haitian-American writer, and she’s written both fiction and non-fiction. She’s a beautiful stylist, she has this kind of deceptively simple style, and she really finds ways to weave in politics and family complexity and women coming of age.

Oh, there have been so many. I was just thinking this morning, going back to the idea of Gothic novels, about the British writer Sarah Waters. She’s a really interesting writer, and she is reinventing Gothic. I wait for every new book of hers to come out. I love Margaret Atwood. I really love her work, and I love that you never know what she’s going to do. She’s honest, passionate, and authentic no matter what she does. And she’s prolific, but at no expense to the quality of her work. I really admire her. I love Edwidge Danticat. She’s a Haitian-American writer, and she’s written both fiction and non-fiction. She’s a beautiful stylist, she has this kind of deceptively simple style, and she really finds ways to weave in politics and family complexity and women coming of age.

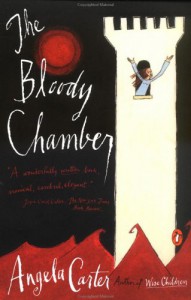

And then I was greatly influenced by Angela Carter. She’s somebody who reinvented literature, as far as I can tell. The first book of hers I discovered was called The Bloody Chamber, and it was a book of short stories in which she reinvented fairy tales in the most sexual, feminist, intelligent, visual way. And then there’s a nonfiction writer, Vivian Gornick, who wrote a memoir called Fierce Attachments, which was one of the first memoirs I ever read. It is a searing mother daughter memoir, just so amazingly insightful, honest, and so evocative of place and time. These are just a few women whose work I really, really like, and have definitely influenced me.

And then I was greatly influenced by Angela Carter. She’s somebody who reinvented literature, as far as I can tell. The first book of hers I discovered was called The Bloody Chamber, and it was a book of short stories in which she reinvented fairy tales in the most sexual, feminist, intelligent, visual way. And then there’s a nonfiction writer, Vivian Gornick, who wrote a memoir called Fierce Attachments, which was one of the first memoirs I ever read. It is a searing mother daughter memoir, just so amazingly insightful, honest, and so evocative of place and time. These are just a few women whose work I really, really like, and have definitely influenced me.

Do you think the term women’s writing, troubling as it may be, holds any weight? Is women’s writing a genre, or is it just a construct?

It’s such a good question. You know, I’d like to say it’s just a construct. And I’d like to say that we’re all writing from the same places, the same passions, the same world views, looking to find truth as we know it and can seek it. And yet, we know that men tend not to read women’s books as much. We know that women are often writing for other women. We know that women, in some ways, have a secret language that we use in person, and it’s there in fiction, too. But, ideally, I would like to say that there’s just writing. And in an ideal world, we would all read across genre and gender and age and geography. That’s the world I want to live in.

And the world you want to write in?

And the world I want to write in. And when I sit down at my page, I believe it is the world I’m writing in.

Further Links and Resources

– Meg Pokrass talks with Janice Eidus as part of the Fictionaut Five series.

– Meg Pokrass talks with Janice Eidus as part of the Fictionaut Five series.

– Guest-blogging at Madam Mayo, Eidus offers “5 Vampire Links to Sink Your Teeth Into.”

– Shopping for a copy of The Last Jewish Virgin? Consider ordering yours from indie bookstore Powell’s.

– Browse the bookshelves of (free) Gothic literature at Project Gutenberg.

– Learn more about Eidus’s other novels and story collections on her website, and read an excerpt from Vito Loves Geraldine‘s title story.

– Via FC2, here’s a brief excerpt from Faithful Rebecca.

– Download this PDF to learn more about Carlow University’s low-residency MFA program (which includes sessions in Pittsburgh and Carlow, Ireland). Janice also teaches writing privately: details are here.