I was suffering my own novel-panic when I read about John Stazinski’s in the Jan./Feb. issue of Poets & Writers—or, more accurately, I had been suffering the panic for years and was in the process of curing it. I was writing a novel. It was my fourth or fifth attempt, and I was finally getting a grip on what it required. Like Stazinski, I had cut my teeth on short stories, then had raged and despaired about how different the novel was, and how absolutely unprepared I was to write one. My first several attempts were eighty-page abortions that gave me fits of nausea and cold sweats to look at.

And so I felt a wonderful shock of recognition when Stazinski described his own panic, and intrigued by this recommendation: “For my money, the best teacher of novel writing is John Gardner. In the midst of my novel-panic, his was a calm voice of reason.” I’d bought Gardner’s seminal craft book, The Art of Fiction, nearly two years earlier, but hadn’t cracked it. Now I raced through it, in near ecstasy, resisting the urge to underline every sentence on every page. Gardner articulated all the hazy, intuitive discoveries I’d gathered from my failures, allowing me to fully comprehend what I only sensed before. I had been groping in the dark, and Gardner flipped on the floodlights. But afterward, when I sat down with my novel, filled with insight and renewed purpose, I couldn’t write.

I wasn’t surprised. The same thing happened when I taught new stories in my classes, when I gave feedback to my writer friends on their manuscripts, when I wrote book reviews or craft essays that parsed how narratives functioned—in other words, whenever I became too conscious of craft.

By “craft,” I mean the techniques and strategies for handling the building blocks of a story—conflict, characterization, plot, description, dialogue, and so on—the value of which seems to be a matter of some debate. Many writers I know refer to craft talk derogatorily as “MFA-ey.” They consider it posturing, or fake expertise, or worse. One writer I know told me he was doing his best to forget everything he had learned in graduate school. I sympathize; writer’s block sets in whenever I think too carefully about craft. But I disagree with those attitudes, because it’s not the craft that causes my writer’s block—it’s the thinking.

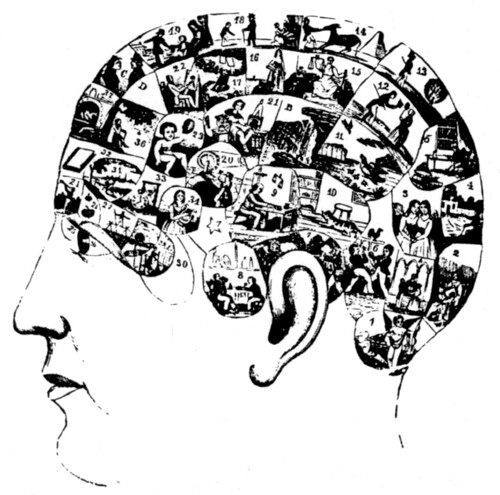

According to an article by Kenneth Kaye in the Feb. 2008 issue of The Writer’s Chronicle, a simplified version of the brain shows two basic regions, the higher and the lower. The higher region is in charge of processes such as math, logic, language rules, moral judgment, and so on—in other words, conscious thinking. When we analyze craft or apply it to our work, this is the part of the brain we’re using.

According to an article by Kenneth Kaye in the Feb. 2008 issue of The Writer’s Chronicle, a simplified version of the brain shows two basic regions, the higher and the lower. The higher region is in charge of processes such as math, logic, language rules, moral judgment, and so on—in other words, conscious thinking. When we analyze craft or apply it to our work, this is the part of the brain we’re using.

But Gardner, Richard Bausch, and Robert Olen Butler have all talked about writing as a kind of dreaming, and dreaming certainly isn’t something we do with the conscious, rational part of our minds. The daydreamer doesn’t decide to drift into thought. She doesn’t ask herself rational questions to determine the direction of her fantasies. In fact, the moment the rational part of her mind kicks in, it interrupts the fantasy, often ending it. That’s the effect that considering craft has on the process of creation. The higher region of the brain takes over, and our dreams recede. To dream, we have to give ourselves over to the lower region of the brain, which is responsible for sensations, emotional responses, movement, and selective memory. That means suspending logical processes like thinking about craft.

But it doesn’t mean that craft has no value, or is best forgotten. Craft is what allows us to give shape to the raw material we dredge from the lower region of the brain, what allows us to produce meaningful narratives rather than jumbles of images, what allows us to produce art instead of haphazard daydreams. As Flannery O’Connor says in Mystery and Manners, “Form is necessity in a work of art.” Craft is how we understand and achieve that necessity.

So how do we reconcile these two issues? The obvious answer is to consider craft ideas only after drafting a story—first write, then revise. But Gardner provides an even better answer: “the true writer is one for whom technique has become, as it is for the pianist, second nature.” In other words, we should understand craft so thoroughly that we don’t even have to think about it, and therefore don’t have to access the higher region of the brain to employ it. It should become so ingrained that it’s intuitive.

The only way to accomplish that is to read and learn and think and practice. When I was a high school freshman, our basketball coach made us dribble and shoot layups left handed. At first it required great concentration. We went very slowly, with great awkwardness, and we missed many baskets. By the end of the year, though, we did it as naturally and thoughtlessly and successfully as with our right hands, and during games, that opened new possibilities for us. A writer who applies new craft ideas is like a basketball player trying his first left-handed shots—not pretty. A writer who avoids craft is like a basketball player who avoids his left hand—the gap will ultimately limit his success.

And this is what novel-panic is all about. When writers learn a new form, our efforts will be awkward and overly deliberate, and we will miss many shots. That doesn’t mean we’re wrong to try, or that we should refuse good coaching. We just have to keep practicing until the lessons are so deeply known that they enter our dreams.

Further Links & Resources

- Daniel Wallace’s recent essay on how to change the way the principles of writing are taught gets at the issue of internalizing craft from the classroom angle.

- David H. Freedman’s article “The Perfected Self” (The Atlantic, June 2012) delves into some of the scientific evidence for behavior modification. If you can train yourself to shoot layups left-handed, and lose weight, could those same principles to writing a perfect story?

- Check out recent FWR interviews with both Richard Bausch and Robert Olen Butler for more from the writing-as-dreaming camp.