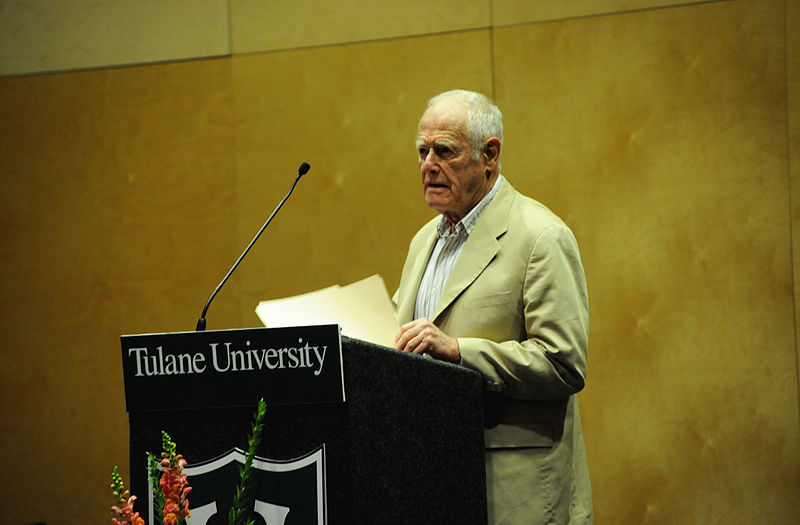

James Salter, American Short Story Writer and Novelist reads at Kendall Cram, Tulane University, New Orleans, November 10, 2010. Sponsored by the English Department as well as the Creative Writing Fund.

“Above all, it must be compelling,” James Salter told the Paris Review in 1993 when asked about his idea of the short story. “You’re sitting around the campfire of literature, so to speak, and various voices speak up out of the dark and begin talking. With some, your mind wanders or you doze off, but with others you are held by every word. The first line, the first sentence, the first paragraph, all have to compel you.”

Long before I ever read those remarks by Salter, I’d already come under the influence of his short stories and, in particular, his crystalline opening paragraphs.

When I am turning the raw material of a new story in my mind, I often pull down one of Salter’s story collections—Dusk and Other Stories (1988) or Last Night (2005)—and skim through them to re-read over and over his opening lines. Salter’s opening paragraphs throw a net around the reader with the kind of lyrical precision often found in poetry.

Salter’s stories brim with the emotional resonance achieved by his accrual of fragments—his writing doesn’t charge ahead so much as it unfolds. Salter’s balance of short declarative and longer lyrical sentences is sharply observant, such as in the opening of “Am Strande von Tanger” (from Dusk and Other Stories):

Barcelona at dawn. The hotels are dark. All the great avenues are pointing to the sea.

The city is empty. Nico is asleep. She is bound by twisted sheets, by her long hair, by a naked arm which fall from beneath a pillow. She lies still, she does not even breathe.

Salter achieves a similar resonance of accrual with the opening paragraph of “Akhnilo” (from Dusk and Other Stories):

It was late August. In the harbor the boats lay still, no the slightest stirring in their mast, not the softest clink of a sheave. The restaurants had long since closed. An occasional car, headlights glaring, came over the bridge from North Haven or turned down Main Street, past the lighted telephone booths with their smashed receivers. On the highway the discotheques were emptying. It was after three.

Salter has another kind of opening paragraph that I admire, too, one that ends with a kind of explosion. The celebrated Russian short story master Isaac Babel once described this possibility of ending a paragraph “like a flash of lightning.” Writing about Babel’s charged opening paragraphs in her stellar craft book Reading Like a Writer, Francine Prose may as well have been writing about my own feelings on Salter. The paragraph, Prose writes, is a bit of “literary respiration… Inhale at the beginning of the paragraph, exhale at the end.” At a paragraph’s end, Salter, like Babel, has a gift for introducing an element of unease: a flash of lighting. The stunning opening of “My Lord You” (from Last Night) is a perfect example:

There were crumpled napkins on the table, wineglasses still with dark remnant in them, coffee stains, and plates with bits of hardened Brie. Beyond the bluish windows the garden lay motionless beneath the birdsong of summer morning. Daylight had come. It had been a success except for one thing: Brennan.

And again in the same collection’s title story, “Last Night”:

Walter Such was a translator. He liked to write with a green fountain pen that he had a habit of raising in the air slightly after each sentence, almost as if his hand were a mechanical device. He could recite lines of Blok in Russian and then give Rilke’s translation of them in German, pointing out their beauty. He was a sociable but also sometimes prickly man, who stuttered a little at first and who lived with his wife in a manner they liked. But Marit, his wife, was ill.

With the openings of both “My Lord You” and “Last Night,” Salter delivers in a single-breath-of-a-paragraph everything a reader needs to compel them to continue reading. With these concisely compressed openings, the reader is invited to lean into the glow of the campfire of literature as Salter methodically builds a foundation word by word.

When considering what the opening paragraph of a short story can hold—and perhaps should—the influence of James Salter is worthy of close consideration.

Further Reading:

Until the publication last month of All That Is—James Salter’s first novel in more than thirty years—he was best known for the shimmering and erotic novel A Sport and a Pastime. The opening paragraph of that novel was the first writing by Salter that contributing editor Joshua Bodwell ever read:

September. It seems these luminous days will never end. The city, which was almost empty during August, now is filling up again. It is being replenished. The restaurants are all reopening, the shops. People are coming back from the country, the sea, from trips on roads all jammed with cars. The station is very crowded. There are children, dogs, families with old pieces of luggage bound by straps. I make my way among them. It’s like being in a tunnel. Finally I emerge onto the brilliance of the quai, beneath a roof of glass panels which seems to magnify the light.