[With original illustrations by the author.]

[With original illustrations by the author.]

Novelist Sarah Van Arsdale (Grand Isle, Blue, and Toward Amnesia) writes and teaches in New York City, where she runs the Atlantic Writers’ Workshop.

I just read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. The whole thing. Starting on page one and ending on page 706. The events in the book span seven years, and reading it seemed to take almost as long.

No wonder. When I embarked on The Magic Mountain, I was recovering from orthopedic surgery—real, major, invasive surgery, in which I was knocked out and cut open so that a surgeon could saw the head off the femur in my right leg and replace it with a metal post. The procedure was necessary to correct an error made by genetics or God, to get me out of chronic pain and able to walk freely again in the land of the well. Apparently, it did that, but first I had to weather a period of recovering from what they call “a major insult” to the body, a period marked by immobility and a deepened intimacy with narcotic medicines.

Why, then, would I want to read a lengthy book packed with intellectual digressions set in a tuberculosis sanatorium in the Swiss Alps prior to the start of World War II? Hadn’t I been through enough? How about something light, or at least short? A Carol Goodman murder mystery, or something by Nick Hornby?

As it turned out, The Magic Mountain was a choice so perfect I’m thinking a copy should be handed out with every pre-admission packet given to surgical patients. When you’re holding 706 pages in your hands, and especially when, like me, you’re a slow reader, you know it’s going to take a long time to get through the book. But when you’ve been told your recovery will be slow and exhausting, you’re thrilled to know at page 200 that you’ve only just begun.

You Could Say I Enjoyed Swimming Regardless of Water Temperature

The pace of the book is just right for the pace of the post-surgery patient, especially the one who feels like a racehorse who’s narrowly averted the glue factory. All my life I’ve been in motion, clambering up and skiing down the mountains of Vermont; taking up tennis, or biking, or anything that involved motion and sweat and muscle; and most of all swimming anywhere I could find water, from the lap pools of New York City to the beaches of France, and, once, very quickly, in the Arctic Ocean. I was, you know, active. Then, three years ago, as I was wheeling around the reservoir on my two good legs, a sudden, sharp pain snapped in my groin, and I limped off the running track to prop myself against the nearest tree.

At first, I figured it was just a pulled muscle, nothing a little ice and rest wouldn’t cure. And yet, this small moment would mark my gradual descent into a world of pain and medical tests and diagnoses, as my athletic activity dwindled. First, the running went. Then the hard, fast walks. Finally, even the swimming hurt. So that by the time I started consulting surgeons, I burst into tears when a doctor asked how far I could walk, remembering how it had felt to be me, so long ago. “About a block,” I sniffled.

Now, post-surgery, there would be more incarceration, long weeks during which I should get out and walk a bit, but also during which I should let the sliced piriformis heal and the muscles calm down and the bone grow back. The last thing I wanted to do was lie around the apartment, and yet, it was the only thing I could do. And here was The Magic Mountain, with writing so slow that it forced me to luxuriate in my recovery. Hans Castorp arrives on page one; on page thirty nine he’s joining his cousin, Joachim, for his first breakfast. Granted, in there we hear about his dreams and we learn a bit about his early years, but still, if each day took forty pages for the rest of the novel, the book would be 10,000 pages. So later on, of course, time is compressed, and soon, as in my own recovery, all sense of time is lost entirely. But the pace remains slow, kind of like the pace at which the doctor rushes to return your call.

Not only is it a huge, long story, but reading it felt like work—the best kind of work. I certainly couldn’t work on my own skimpy novel while I recovered, but at least I could read something with some substance to it, especially as my other main source of entertainment was watching Sex and the City reruns from Netflix: not work. But The Magic Mountain? Work. Even though it’s engaging, and has pages and pages of gossipy stuff and a lot of truly funny moments, it isn’t what you’d call light reading; at many points, the dialogue turns to philosophical discussions about illness, religion, and time, which a reader’s mind, if addled by pain or pain killers, can barely penetrate.

Topics of Discussion in The Magic Mountain: medicine, religion, and time

But as a reader and a patient, you don’t have to penetrate these conversations; it’s enough to sit back and nod, turning the pages, letting the thoughts of Thomas Mann as expressed through Herr Settembrini or Herr Naphtha wash over you. There also was something I liked about reading these deeper discussions; surgery brings you frighteningly close to your own human-ness, your own body, your own mortality. When the surgeon calculates with you the expected longevity of your metal hip and the expected longevity of the rest of you, your mortality becomes difficult to dodge. I’d been utterly exposed and vulnerable and unconscious on that operating table, thoroughly dependent on the competence of others; if the surgeon or anesthesiologist had looked away at the wrong moment, I’d be dead. Plus, the predictability of the surgery—at least, on the surgeon’s part—reminded me that I’m really not all that special, at least in terms of my human-ness: I’m just another animal, another packet of blood and tissue and bone, and something that could be called “the breath of life.” And so I wanted to read—a little—about characters thinking about these matters.

Better than all that was something that utterly surprised me: my own recovery was following the path of Hans Castorp’s experience at the Sanatorium Berghof. We read fiction in part to develop empathy and compassion for characters unlike ourselves, and yet, sometimes, there is this blissful, perfect symmetry between reader and character. Here I had found my twin, at least for the moment. From the first page, I had noticed the similarities between us, and then I started looking for them, and then I started learning from Hans Castorp’s journey. Because despite the ordeal of my recovery I wasn’t doing this alone; he was beginning his stay at the sanatorium just as I was beginning my stay at my own sanatorium, otherwise known as my apartment in Manhattan. Granted, there are some differences between me and Hans Castorp: for example, he’s got a view of the Swiss Alps and five sumptuous meals served in the dining room each day. When he does travel outside of the sanatorium, he goes by carriage, whereas I had to schlep myself down to the A train, beating New Yorkers aside with my cane.

Getting Around New York Proved Somewhat Difficult

But regardless of the differences in our settings, as Hans Castorp settled in to his stay, he showed me how to become a patient—how to, as Susan Sontag would have it, claim my citizenship in the kingdom of the ill.

The first stage of claiming that citizenship is denying it. “Everything has its limits,” Hans Castorp tells his cousin on page 86. “And there has to be some way for me to tell that I’m only a visitor up here among you all.” The kingdom of the ill is not one that many enter willingly, and me and Hans Castorp, we liked our lives “down below,” where there is work and play, walking freely among out fellows, and music and dancing and carrying on. Hans Castorp was young, about to start his first job; I was, well, not young, but certainly not old. There was nothing else wrong with me, and there was nothing at all wrong with Hans Castorp except a small “moist spot” on his lung—the first sign of TB, discovered in such a way that the reader is never really sure if Hans Castorp has been made sick by medicine, or if medicine has made a miraculous and timely intervention. In either case, we’d both been living in the big, rich, dappled world of parties and discussions and art and readings and cocktails—the kingdom of the well. But we’d been suddenly asked to leave. Deported against our wills. We were told that our bodies were sick, and had to rest. And we’d been exiled to a foreign country to recover.

But we were just visitors, we told ourselves. Hans and I both looked with some contempt at the other, truly ill people in our midst. He wasn’t, at the start of the book, even a patient; he was only visiting his cousin. And I was sure that my rosy health, my athletic prowess, my sheer enthusiasm for life would allow me to speed past my older, truly decrepit counterparts I’d witnessed in the waiting rooms of the doctor’s offices prior to the surgery, and now in the physical therapy gym afterwards. I was the anomaly, after all; I’d just had a spell of bad luck from which I’d quickly recover. I’d enviously watch the elderly patients peddling on the stationary bikes as I lay on my mat with strict orders to complete only five leg lifts. But no! I can do ten! Twenty! Just watch me!

Because what I saw when I looked inward was the runner, the swimmer, temporarily sidelined by an injury because I was athletic. And that very athleticism would rebound me in no time, I figured. But first, I just had to rest a bit. Follow the prescription to take it easy. Of course, I should try to walk, but for the first several weeks, I should mostly stay home, let my body recover from its losses.

Hans Castorp and I Made Good Use of Our Rest Cures

And like my own regimen for recovery, the paramount treatment at the Sanatorium Berghof consisted of the daily “rest cures,” during which all patients retreated to their outdoor chaises regardless of the weather and “assumed the horizontal position;” it was believed that the body would restore its strength simply by lying still in the fresh, sometimes freezing, mountain air.

But even after we’d accepted that we would, however temporarily, have to reside among the ill, we continued to rebel. Hans Castorp insists on taking a long, unsupervised walk. He fantasizes about making a “wild departure.” He keeps reminding us all that he’s leaving in three weeks. Even as far along as page 114 he protests that he’s had his “fill of horizontal living,” and I cheered along with him: Not this pig! But from the early pages of the book, it was clear he was going down with the rest of them, and he did, gradually succumbing to the rest cures and twice-daily temperature-takings, gradually slipping further into the small world of the ill. With me, tumbling along after him.

I had similar thoughts of wild departures. In my first weeks home from the hospital, I tried to go out, even making it to a couple of publishing parties. So what if it’s downtown? I’ve got my cane! But I felt awkward and uncomfortable, unable to stand for more than a few minutes, still feeling bloated and puffy from the surgery; I soon realized that it wasn’t just that I couldn’t walk easily, but it was that I was miserable, either in pain or stupid from the narcotics, unable to feign interest in anyone except, well, me.

And for a brief period of time after this I continued to make dates for lunch; I read the movie listings to suggest films to see with friends. Because I was certain that, like Hans, within about three weeks I’d be back to my usual pre-surgical racing around, if not to my pre-pain racing around. And then I’d hear myself on the phone, calling to cancel something, in a cascade of emotions: first, terror at slipping even further from the world; then relief at my friends’ or colleagues’ understanding; followed by excitement at knowing I could now lie back for another guilty afternoon of reading. As my recovery went on, I knew my attempts to stay engaged were pointless, and yet I needed to keep up this illusion—for my own sanity—that I was, really, getting better.

But by the time those magical three weeks had passed and I wasn’t back on my feet, I had come to accept defeat, and to unpack my boxes in the kingdom of the ill. I’d get myself downtown for physical therapy, but otherwise, the world had to come to me. And soon there was nowhere I preferred to be than my equivalent of the sanatorium’s lounge chair—my brown sofa, complete with pillows and ice packs and cats.

The Cats Tried To Hold Back Their Excitement at My Increased Presence at Home

Post-surgery, there is one place where you feel comfortable and safe, where you don’t have fight for a seat on the bus or struggle up and down steps, where you don’t have to juggle the cane in one hand and the umbrella in the other, where no one looks at you pityingly. That place is home. And why bother with all the rest of the world when you still have 400 pages of The Magic Mountain to read? This was where my fellow inmates were; these were the people who really understood me.

So as much as I had resisted illness, once it came, and once I became a long-term patient, I began to lose my taste for the world down there. Around the time I settled in to my recovery, I came upon a story in The Magic Mountain of the girl who, having regained health, tried to falsify a fever, so desperately did she want to remain in the sanatorium.

Three Methods For Faking One's Fever

“’What is there for me down below?’” she cried. Yeah, what? I cried back, getting another bag of ice and stretching out on the sofa yet again. What’s so great about the big, busy world where the person with the cane is pushed aside in the rush to the subway, where the guy in the wheelchair is nearly run over in the street, where it’s all “getting and spending/late and soon”? How much better a life it is to sit still, watching the bright afternoon light fade into dusk. A privileged life, to be sure; and increasingly, I became more aware of how fortunate I was to be able to indulge in such a protracted recovery. The patients at the Sanatorium Berghof are similarly people of means: where I was living off my continuing income from my editing job, they were living off their investments, granting all of us a luxury of rest unavailable to most of the world. And unpleasant as my own recovery was, I know I was very lucky indeed to have good food to eat and a nice apartment to lie around in and a refrigerator with an ice crusher.

But perhaps the fundamental reason engagement with the bigger world—the world of the well—becomes so difficult is that when you’ve assumed the horizontal position, your perception of time changes. And Mann often doesn’t clearly delineate the passage of time for us. Sometimes he even admits that he’s obfuscating it, tidily replicating the experience of the ill person. Each day is the same as the day before, stretching out before and behind you, time becoming an elastic band that can bend to accommodate another rest cure, another session of icing, another meal. Or it collapses, and you look up, surprised to see it’s time to have dinner again, unsure of the day of the week, but certain of the exact number of hours since the surgery.

To the ill, the time you’re laid up seems both absurdly long and much too short. In the book, each day’s final rest cure before supper is “a fleeting, shallow hour and a half.” Indeed, that’s barely enough time to get yourself into bed, read a few pages, and have a nap. Let’s hope you remembered to turn the phone off. When my days were interrupted by physical therapy, or visits from friends, or deliveries of groceries, bitter resentment arose in my heart—my rest cure has been shortened! My bed awaits!

Because the rest cure did its work—at least for me. Once I was through rebelling against the constraint, I came to feel I needed the rest. My days were made up of reading, making a meal or two, taking a little walk down to my building’s garden. I started to feel that simply allowing my bones and muscles to lie still really was allowing them to heal, and this theory was shored up by the philosophy in evidence at the Sanatorium Berghof.

The flux in temporal perception exacerbated the ebb of my concern with the “real” world; the world of the Berghof Sanatorium seemed much more important. I’d pick up any necessary news at physical therapy, filtered through the therapist so it was more like telegraphic gossip: Sotomayor was chosen. Michael Jackson died. Okay. That’s all I need to know. How many reps of this leg lift do you want me to do? Because even before I’d finished my exercises, my mind would be wandering, anxious to return home. What will Hans Castorp’s x-ray reveal? What topic too deep for my narcotic-washed brain will Herr Settembrini discuss next? Will Clavdia Chauchat slam that dining room door one more time? And, most importantly, is that good old pain seeping in again? And what time is it now, and when was that last Vicodin? After all, it is the regularity of a routine that is comforting, not necessarily the routine itself. And soon I had learned to mark my days with pages and pills and rest cures.

Hans Castorp Modeling the Ever-Present Pocket X-Ray...

This is not to say that I wasn’t immensely happy to have friends visit me; they made me feel as if I was still among the living. But the people who understood me best were the inmates of the Berghof. When you’re recovering from surgery, really all you want to read, think or talk about is illness and health. And there is plenty of discussion of such topics in The Magic Mountain. They’re as obsessed as you are! For God’s sake, they take their temperatures twice a day, and record their findings on a chart! They carry their chest-x-rays around with them!

And yet, you also want to read, think or talk about absolutely anything else. I could see that my insistence on having my rest cures each day could become a way to just give up the world below for good; I could see how easily I could become one of those people who are occupied with their state of health or illness to the exclusion of everything else, clinging to my identity as a patient because my other identity—my own true identity—had slipped so far from my grasp.

...and Close-Up Detail of Same.

It’s understandable how this happens: the world below is demanding, especially if you’re at all compromised. And for someone like me, who had defined herself, in part, by athleticism, the difficulties I faced doing such a simple task as walking to the corner for the paper was a disheartening reminder that I was not well—no longer myself. So why not become someone else? Someone who scorns that other, more vigorous world? Plus, the little world of recovery becomes fascinating: I started really caring about what my physical therapist did on vacation; I looked forward to certain television shows; and I became increasingly attached to Hans Castorp and his pals. After all, this was where I’d come to feel I belonged.

It’s natural, then, to see why some people embrace their identity as a patient, despite the fact that it’s a restricted vision of their lives. But where do others find the mettle to adamantly refuse this type of self definition? In addition to Thomas Mann’s fictional story pulling me through, it was also the very real friendship and memoir of the Swiss-American writer Christoph Keller that gave me another kind of hope. Keller has a degenerative muscular condition that landed him in a wheelchair in early adulthood, granting him irrevocable citizenship in the kingdom of the disabled. Yet he’s the image of a hale, healthy, vigorous man. He remains undaunted in his engagement with the world, even when the world throws up very real—literally, concrete—barriers in his path. Yes, he is a citizen in the kingdom of the ill, but he manages dual citizenship, with a marriage, a creative life, a social life that I envied even before my own pain began. And yet other people who have few physical problems seem sickly, as if eager for an easy passage granted to the ill.

The Passport is in Order

Keller’s autobiography, The Best Dancer, allowed me to see that the decision about how to live as disabled often has more to do with personality that physicality. More vulnerable, more in need of assistance, more at the mercy of the stairs and doors and curbs, you have to choose whether to retreat or to continue pushing through the world—a world now much more challenging to navigate. Knowing Christoph allowed me to see that even if I was permanently deported, there would be ways I could choose to be engaged and vital. That people can harness their creative tenacity to propel themselves around sometimes stunning obstacles in order to remain in the “world below.”

Because the truth is that I came very close to answering the siren’s call to identify myself as sick, nearly wrecking on those dangerous reefs as I made my way back toward the land of the well. Even months post-op, I still worried—sometimes in tears—that I wouldn’t be allowed back, that something had gone Terribly Wrong and I would forever be in pain. And this despair could have been enough to sink me. I tried to remind myself of what the doctor had said in the pre-op exam. He’d assured me that my heart rate was still athlete-slow; he said that I’d come back after the ordeal. “You’ve got a lot in the bank,” he told me, and perhaps that was true psychologically, too: perhaps my enthusiastic, sometimes verging-on-desperate, engagement with the world was so deeply a part of who I am that even when it was reduced to a thin filament, it was enough to bring me back.

Aerodynamics Prove Helpful

This happened slowly, of course. Bit by bit, day by day, step by step. Though I might just as easily have said “chapter by chapter.” Because during the process of coming back to myself, I was reminded over and again how powerful and instructive a life on the page can be.

Yet the appeal of The Magic Mountain—and the reason that it’s a book that ultimately helped me recover—can’t simply be that that it was really long and reflective of my own experience. When my father died, friends pressed upon me books about characters “dealing with death,” none of which I read. Instead, I read short stories that were about falling in love and travel and family—about life.

There is something inherently fascinating to the ill person about the illness; the world shrinks so that each crossing of the living room or each leak of the ice bag is utterly absorbing. Conversely, unless it’s presented in a finely-rafted prism, there is something inherently dull about someone else’s illness. And it isn’t only that it’s dull, but it’s frightening. As Sontag points out, every one of us will at some time become a citizen of the kingdom of the ill, if only for a short bout of a summer cold or a winter flu. The last thing we want to do is enter that little world of someone else’s illness, if we don’t have to. Perhaps this is why visiting the sick is considered in many religions one of the greatest good deeds—you really, really, do not want to sit there and listen to a sick person whine about the pain, the side effects, or the inconvenient schedule of Seinfeld re-runs.

One reason The Magic Mountain was so instructive was that it was fiction. Even better than mirroring my own experience precisely, The Magic Mountain, being a novel, takes place in an utterly different setting, with a protagonist very definitely not me, which allowed me to trace my journey along the path of Hans Castorp’s. At times fiction can allow for more reflection of our own experience, just as Roger Tory Peterson argued a drawing of a bird allows a birdwatcher to more accurately identify a species than a photograph does due to the fact that the drawing holds more room for the imagination. And because I wasn’t looking for an exact model for my experience, I was able to inhabit the imaginary world of Hans Castorp and company in a way that allowed the crucial, more subtle similarities to resonate. The book also afforded me a way to gain distance from myself, which I needed to offset my self-absorption—reading The Magic Mountain was like taking an aerial view of the Sanatorium Berghof, a view I could then take with my own suffering and recovery.

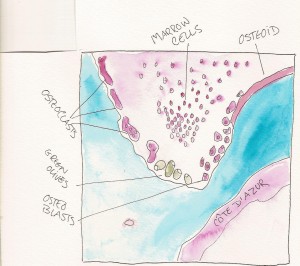

Osteoblasts As Interacting With Green Olives

And it was, after all, more productive to lie back and wait. My body had been healing all on its own, the bones laying down new oseteoblasts, the blood pumping through my veins, the lymph cleansing out the detritus. All I had to do was wrap myself in my blanket and pick up my book. Relax. Rest. Savor it. You only have two hundred and ten pages to go.

Because as I neared the final quarter of the book, I made a superstitious promise to myself that when I finished The Magic Mountain, I’d be finished with the first, most difficult, most exhausting round of recovery. I’d get up from my bed and walk, freely, happily, with no pain at all. I’d go downtown! I’d make a date and keep it!

This happened and didn’t happen. By about five weeks after the surgery, I was able to see that the pre-surgery pain was gone, leaving me with only the post-surgery pain, which, everyone said, would abate. I was now able to walk the two blocks to the gym, where I was allowed twenty minutes on the stationary bike. I was getting back to work; I had a new editing client; I had a class to teach on-line.

As I rounded the corner to page 600, I was much better than I’d been. But what about the magic mountain? Was I ready to make my wild departure? At page 600, I was about to receive a visit from my sister, and I knew I’d be distracted from my reading schedule. I wouldn’t have all my luxurious rest cures. It would be a breakneck pace of talking, eating, and napping, with barely, what, an hour of reading during the day? And beyond that weekend, I’d gradually be venturing out more, leaving behind my fictional comrades for the real, terrifying, complicated, wonderful world below.

But I was afraid to put the book aside for a whole weekend; what if that somehow delayed my recovery? Or set me back? I wanted to finish it as soon as I could and stroll happily out the door on Monday morning, but I also wondered if I had the strength to turn my back on this place and leave it—let alone my fellow citizens—behind.

But regardless of my fears and hesitations, I picked up my reading pace and dedicated my entire day to the book. I lived in the little world of the Sanatorium Berghof all day, saying goodbye to my friends there. Sorry, I have to start making way back to the world down below. No, I mean really. Goodbye, goodbye! Farewell Settimbrini, Adieu Frau Chauchat! Godspeed, dear Joachim! Good luck, my beloved, sweet Hans Castorp! And the pages flipped past, and then I was done.

Done.

The Beautiful Sidewalk with Blue Sky and Little Dog

Dazed, I slowly walked the two blocks toward the gym. Spring had fully arrived; the hydrangeas were plumping up, the air was filled with sunny warmth. The walk was easy, with my cane. I passed the ice-cream truck jingling its happy song, watched a little dog tugging at the end of a leash. I looked up: the good old blue sky, the same one that had sheltered Hans Castorp and Thomas Mann. The whole world was still here, I realized, if not waiting for me, then spinning still. And soon I’d take those few running steps and jump back on. I would get better. I would come down off my own magic mountain. I would.

Further Resources

To read more about Sarah Van Arsdale’s adventures and exploits, you can follow her on her blog, A Blue True Dream of Sky: Amateur athlete, against her better judgment, reports on total hip replacement and recovery, with charming illustrations.

For more on Christoph Keller and his memoir, The Best Dancer, visit Ooligan Press. The site also includes an interview with the author. Pick up your copy of the book from a local independent.

Sarah recommends the Vintage paperback edition of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, translated by John E. Woods.