Until recently, my wife and I lived in Arizona, where she played in a community orchestra. Many of the people who attended the orchestra concerts were related to one of the musicians in some way, and the rest tended to be older folks. I am in no way a youngster, but as I shuffled past the frail, elderly couple seated at the end of my row one night, the sheer contrast made me feel like a teenager. I sat down and, like a teenager, began fiddling with my phone—checking email, sending texts, all the usual. The woman beside me, who might have been in her early eighties, said in a surprisingly strong voice, “Can you get the score on that?”

“Sure,” I said, smiling like a minor god of technology. “Score of what?”

At that the woman gave me a look of something like surprise and pity. How could I be so young and virile and yet so ignorant? “Marquette – Syracuse,” she said. “I’m pulling for Marquette, but Albert”—she gestured toward the man I assumed to be her husband, who was absorbed in the concert program—“says Syracuse is going to win.”

I tapped the screen of my phone a few times and reported that Syracuse was up by 2 late in the first half. As I did, I noticed that the woman’s left hand, wrinkled and discolored by liver spots, was freshly bandaged and badly bruised.

“I fell last night,” she explained. “I got up in the middle of the night and tripped on the carpet, or something—I reached out for the dresser, but missed, then fell on this hand. Hurt something awful.” I made a vague sympathetic sound. “I was hoping it was bad enough that we couldn’t fly tomorrow,” she said. “We’re supposed to go to Rochester, and I do not want to go to Rochester. I told Albert, ‘Look—now we can’t go.’ And he was so angry with me. He gets angry. He accused me of falling on purpose.”

As I was thinking of a way to ask what horror awaited them in Rochester, she continued. “He bandaged me up himself. He doesn’t like for me to see the doctor.” She turned toward me to say that part, and for the first time I noticed a bruise on her cheekbone. It looked older, less vivid than the bruise on her hand. At the same moment, Albert, without looking up from the program, reached over and rested his hand on his wife’s knee. But “rested” isn’t quite accurate. He put his hand on her knee and, spreading his thumb and forefinger, applied pressure to either side of her kneecap.

Beginning fiction writers used to be—and perhaps still are—told that fiction is about conflict. Someone wants something and some one or some thing stands in the way. For a while, there seemed to be a proliferation of essays protesting that to discuss narrative in terms of “conflict” was seen by some to reduce narrative to a particularly male lens. This may be true. It might also be true that “power” is not the best word to describe the quality I want to discuss here. I considered “authority,” but that conveys a certain self-awareness and agency that is not always present in the powerful, and someone can hold a position of authority without being particularly powerful (think Substitute Teacher). I considered “dominance” and “influence,” but those terms seem too nebulous. One of my graduate students suggested the term “You know,” as in, “When a character has, like, you know.”

But “power” seems right, as does “authority” when a character is aware of his or her power over others. This quality is by no means exclusively masculine, and both men and women know it when they feel it.

There are many forms of power, more than might be immediately apparent. Many are disguised as something else, including weakness. It’s useful for writers to consider the different forms power can take, and the various ways power can be wielded, and how a narrative actively works to expose various types of power held by its characters. Why? Because when we get stuck in our attempts to develop certain characters, or when scenes or even stories begin to feel static, enabling characters to draw on their power reserves will make them more dynamic. Fiction that recognizes the different forms power can take more accurately mirrors the complexity of life. Anyone with a teenage son or daughter knows how quickly authority can evaporate, as when a young Stella McCartney reportedly told an interviewer that having a father who had been one of the Beatles was “embarrassing,” or when a certain MacArthur recipient searched his kitchen for his car keys, while his teenage daughter stood by the door saying, “Where’d you leave them, Genius?”

There are many forms of power, more than might be immediately apparent. Many are disguised as something else, including weakness. It’s useful for writers to consider the different forms power can take, and the various ways power can be wielded, and how a narrative actively works to expose various types of power held by its characters. Why? Because when we get stuck in our attempts to develop certain characters, or when scenes or even stories begin to feel static, enabling characters to draw on their power reserves will make them more dynamic. Fiction that recognizes the different forms power can take more accurately mirrors the complexity of life. Anyone with a teenage son or daughter knows how quickly authority can evaporate, as when a young Stella McCartney reportedly told an interviewer that having a father who had been one of the Beatles was “embarrassing,” or when a certain MacArthur recipient searched his kitchen for his car keys, while his teenage daughter stood by the door saying, “Where’d you leave them, Genius?”

Power and authority are slippery, elusive, their sources sometimes hard to define.

Power is also constantly shifting. No matter what job we hold, no matter how much money we make, we’re likely to find ourselves ceding authority, at some point, not just to someone wealthier or physically stronger, but to a proctologist or plumber. A brilliant scholar can seem doddering in the presence of the twenty-year-old who knows how to solve his internet connection problems, and there is no end of professionals with the power to hire and fire employees but who are themselves answerable to company presidents and boards of directors and dependent on underpaid assistants, not to mention their auto mechanics and personal trainers.

That encounter at the orchestra concert provides a compact illustration of the shifting of power in a scene.

We have three characters, initially defined as Our Hero and Some Old Couple. The details of the dramatic context, or setting, are relatively inconsequential aside from the fact that they force our characters into close proximity—always a promising situation for drama.

As the scene begins, our hero has, or imagines he has, a certain narrowly defined superiority, based solely on the fact that he is less physically decrepit than the older couple.

Almost immediately, though, the woman scores what would be called, in wrestling, a reversal, as she is not only strong of voice but clearly more knowledgeable about March Madness than our hero.

The woman’s authority is undercut somewhat when the story calls attention to her vulnerability, in the form of her injury; but because she is assertive, and doing nearly all the talking, dramatically, she retains power. She’s at center stage, controlling the conversation; our hero has been relegated to listener, even been made the butt of a small joke. His assumed superiority has been exposed as pathetic, simple vanity.

Through all of this, the husband, Albert, has been inactive, dramatically neutral. But the combination of the woman’s dialogue (what she says about Albert’s anger, and the fact that he doesn’t like her to go to doctors) and the disturbing physical evidence of the bruise on her face, creates significant subtext. Albert’s gesture—reaching out not as an act of love or companionship, but to apply pressure to his wife’s kneecap, quite possibly to silence her—suddenly makes him the most powerful figure in the scene: a dark, threatening force.

From this point, we might imagine the scene unfolding in many ways. One would be for the woman to fall silent, intimidated; another would be for our hero to intervene in some way; yet another would be for the concert to begin, creating suspense, as the scene would need to continue without dialogue. All of those are promising scenarios.

What are some of the kinds and sources of power? We could start with the most primal: physical strength, which would quickly be followed by the possession of the means to do physical harm to others (bricks, bats, guns, matches, rolling pins). Also primal is sexual power, or the power of sexual attraction. A character can have power via possession of a desired object: in the film Casablanca, power belongs to the bearer of letters of transit that allow the holder to travel freely in the parts of Europe controlled by Germany; in The Great Gatsby, Tom Buchanan’s power comes in large part from the fact that he has Daisy, which is what Gatsby thinks he wants. A character can also have the power of possession of knowledge, or information. The power of enchantment can be related to or distinct from sexual attraction: think of Calypso’s hold over Odysseus, and The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World’s hold over the villagers in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s short story. Intelligence or cleverness is a source of power at work in a great many folktales; wealth and control of resources are sources of power everywhere. Power can take the form of moral, emotional, or psychological dominance, and in all sorts of recognized authority, from store clerk to state senator, from classroom teacher to CEO, from parent to probation officer.

One of the reasons power is in flux is that it is often contextual. When a policeman pulls a car over, he has authority granted by his job, supported by the law and by the pistol on his hip; when that same man calls a woman the next day and asks her to go out to dinner with him, that particular authority doesn’t do him much good (see Jean Thompson’s “Mercy”). When my wife taught high school English many years ago, she developed a habit of double-checking her appearance before running out to the store, as there was a good chance that at least one of her students would be bagging groceries. The authority she had worked so hard to earn in the classroom could be undercut by one dash for milk wearing sweatpants.

Thinking in broad terms of the powerful and the powerless—say, people who have a lot of money and people who don’t—does not serve realistic fiction well. While a wealthy person may have access to better medical resources, he or she can still be relatively helpless when confronted with disease, or a wayward child. Conversely, someone can be ill or bedridden or agoraphobic but nonetheless exert tremendous control over one or more people around them, usually family members (see Ray, the wheelchair-bound father in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk). Most of us can recall a moment when a poor, homeless person exerted some power over us, even if only enough to cause a momentary twinge of guilt. In Marisa Silver’s Mary Coin, the title character, a migrant worker raising her children on her own, is powerful in her interactions with others despite her overall vulnerability and the near-impossibility of her improving her socio-economic status.

Thinking in broad terms of the powerful and the powerless—say, people who have a lot of money and people who don’t—does not serve realistic fiction well. While a wealthy person may have access to better medical resources, he or she can still be relatively helpless when confronted with disease, or a wayward child. Conversely, someone can be ill or bedridden or agoraphobic but nonetheless exert tremendous control over one or more people around them, usually family members (see Ray, the wheelchair-bound father in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk). Most of us can recall a moment when a poor, homeless person exerted some power over us, even if only enough to cause a momentary twinge of guilt. In Marisa Silver’s Mary Coin, the title character, a migrant worker raising her children on her own, is powerful in her interactions with others despite her overall vulnerability and the near-impossibility of her improving her socio-economic status.

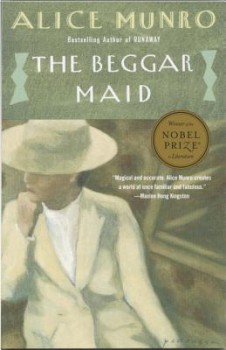

Power can be disguised, then, in many ways; even as its very opposite. In a key scene in Alice Munro’s “Royal Beatings,” Rose is physically punished by her father, at the behest of her stepmother, Flo, in what we are given to understand is something of a family ritual. Flo has psychological power over her husband; she’s able to get him to do something he is reluctant to do. He has obvious physical power, as well as the authority of the patriarch: in their world, it is his responsibility to discipline his child, and he hits her with his belt. But when Rose is sent to her room, presumably as further punishment, Munro exposes a darker truth:

[Rose] has passed into a state of calm, in which outrage is perceived as complete and final. In this state events and possibilities take on a lovely simplicity… she floats in curious comfort, beyond herself, beyond responsibility… in her pure superior state.

For this brief period—in the aftermath following each beating, and despite her physical pain—Rose is “superior.” And this is no delusion: Flo, responsible for initiating the beating, brings Rose her favorite foods, and fawns over her. Rose’s role as victim is empowering.

I want to be very clear: Munro’s story does not argue that to be beaten is to be powerful. Very often, to be beaten, or cheated, or betrayed confers no compensatory strength on the victim. But here, in this story, in the family Munro describes, having been beaten gives Rose power, a moral superiority, due to the fact that her father and stepmother feel guilt about what they’ve done. And that’s a critical point: power does not exist in a vacuum. To have a million dollars in cash is not much help if you’re stranded alone in the desert without water; to be able to deadlift 500 pounds is not much consolation if your heart is broken. In Ralph Ellison’s “Battle Royal,” the young black boxers are physically strong, but that strength is no match for the power of the white businessmen who pit them against each other and humiliate them—in their world, race and class trump physical strength. In Munro’s story, Rose might feel morally superior to Flo and her father no matter what they felt, but their guilt and shame are what give her power over them, temporary as that advantage might be.

This raises the issue of context, or the arena in which characters’ powers are revealed. Lesser fiction often suffers from one-dimensionality in this way. We see powerful people where they’re powerful, weak people where they’re weak. But interesting things tend to happen when characters are removed from the places where their power is most potent, like those boxers in “Battle Royal,” or when the exercise of their power is directly linked to a weakness, as when Flo has Rose beaten only to feel immediate remorse. Once Toto pulls back the curtain concealing him, the Wizard of Oz is just another white-haired man with a hot air balloon.

Beginning writers’ stories are often highly dramatic, heavy on plot and action. They also tend to focus on what we might call Yes/No conflicts. This is the kind of story focused purely on someone who wants something and someone else who doesn’t want him to have it. Stories of direct opposition. Often, instead of exploring characters or a situation, the writers of such stories hope high-stakes action will carry the day: hence violence. And who can blame those young writers, given that most of the fiction they know comes in the form of popular film and television, which favors dramatic confrontations between similar or complementary powers.

We see a simple illustration of those types of confrontations in sports. Two hitters engaged in a homerun-hitting contest are using similar powers. A pitcher and a hitter are using complementary powers. These kinds of conflicts are particularly common in action and adventure stories. In The Princess Bride, the Man in Black has to win a swordfight against Inigo Montoya, the master fencer, then he has to defeat the giant, Fezzik, using only his strength, and finally he has to beat the clever Vizzini in a battle of wits. It might seem obvious that the swordfighter who can beat the master fencer could just slice up Vizzini, but that’s not how this game is played: all the conflicts are carried out using similar powers. In contrast, a typical superhero film might feature complimentary powers: the villain of the day has a stockpile of Kryptonite, so can hold Superman off—that sort of thing.

To encourage students to create stories that recognize dissimilar powers, I give them a simple exercise: write a scene with three characters in one room. At some point during the scene each character has to have authority over the other two. The power or authority that the characters assume cannot be physical—no guns or fighting. I even discourage violent arguments. No yelling. The final caveat: the characters must have different sources of power. They can’t, for instance, each have information that the other two want.

The assignment has two common results. The writers invariably learn something new about their characters, just through the rotation of authority. And the scenes they revise in this way are nearly always the most dynamic scenes in their stories.

The idea for that assignment came from Ernest Hemingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” In that story, Francis Macomber and his wife, Margot, are on safari in Africa, guided by the hunter Robert Wilson. While there are also native helpers hired by Wilson, and a particularly thoughtful lion, Francis, Margot, and Wilson are our main characters. In terms of the safari, Wilson clearly holds the greatest power, as he is an experienced hunter and guide. He knows the country, he knows the tendencies of the animals they’re hunting, and he is responsible both for his American clients and for the natives who work for him. He speaks and acts with authority. In terms of the safari, Francis is the second most powerful, as he’s paying for the trip, he’s hunting, and he’s a decent shot. Margot, along for the adventure, is not hunting, and Wilson doesn’t bother to include her when he instructs Francis on how to kill the animals.

So that’s one of the story’s tiers of power: involvement in and mastery of hunting. No matter what you or I might think about shooting animals for sport, in the world of this story, knowing about hunting and being able to hunt well means something. Wilson’s power is contextual: in these circumstances, he has the greatest authority. If the three of them were, instead, playing tennis, Francis, the racquet sport champion, would have the most authority; if they were on a photo shoot, Margot, a professional model paid to endorse various products, would have the most authority. But the story takes place in Wilson’s world: on the hunt.

Like many good stories, “The Short Happy Life” draws our attention to more than one tier of power. One of the others we might call sex appeal. In this realm, Margot is most powerful. Francis Macomber married her for her beauty, and Wilson admires her, in the way Hemingway’s men admire women: “This was a very attractive one,” he says.Margot’s power arises from the fact that both men find her desirable, and she knows it. She also knows that although Francis is wealthy, he isn’t good enough with women to trade up. If that sounds unromantic, well, the story isn’t about love. In this story, sexual appeal is a kind of currency, albeit one with an expiration date.

Like many good stories, “The Short Happy Life” draws our attention to more than one tier of power. One of the others we might call sex appeal. In this realm, Margot is most powerful. Francis Macomber married her for her beauty, and Wilson admires her, in the way Hemingway’s men admire women: “This was a very attractive one,” he says.Margot’s power arises from the fact that both men find her desirable, and she knows it. She also knows that although Francis is wealthy, he isn’t good enough with women to trade up. If that sounds unromantic, well, the story isn’t about love. In this story, sexual appeal is a kind of currency, albeit one with an expiration date.

A third tier of power in the story is one we might call honor. For much of the story honor is closely aligned with being a good hunter; but there are other factors. Being afraid of a wild animal is not necessarily dishonorable, but being a coward is. Talking openly about your feelings can also be dishonorable. Because the story’s code of honor seems to be defined by Wilson, at the outset he is most powerful in this category. The cards seem stacked in his favor.

When Macomber, his wife, and Wilson set off on safari, Wilson ranked highest in hunting and honor, Margot in sex appeal—but those facts weren’t consequential, because no pressure had yet been placed on the characters. If we imagine, for a moment, Francis and Margot going on safari with Wilson, Francis shooting his big five, the entire trip unfolding with no more drama than the usual exotic vacation, the fact that the characters were unequal in power or authority would be inconsequential. After all, Wilson, the guide, is supposed to be the best hunter. Margot, the former model, is supposed to be most sexually attractive. Characters can be unequal in power without any tension arising. If, for instance, a highway patrolman pulls a car over and gives the driver a ticket for speeding, power is exercised, but there is no surprise, no challenge. If, however, the driver resists the officer, or says that he’s a local celebrity, or offers the officer a bribe, or if the highway patrolman tells the driver he’ll tear up the ticket if the driver will take a suitcase to a nearby gas station for him, things get more interesting.

The writer’s challenge, then, is to create a situation that destabilizes the characters in such a way that their powers—their potential strengths and weaknesses—can be exposed. If we were going to make a not particularly interesting Hollywood film based on Hemingway’s characters, we might get them out into the wild and then have something endanger Wilson and his men, so that Margot and Francis would need to rise to the occasion or lose their lives. But that’s a recipe for an adventure story. Hemingway does something similar but significantly different: he has something happen to Francis, something that reveals character.

When the story opens, that significant action has already occurred; the characters are under pressure. Wilson, Francis, Margot, and the rest of the hunting party have just returned to camp after a lion hunt, which has gone badly. While we don’t immediately learn what happened, the tension is evident, and we’re told Francis “had just shown himself, very publicly, to be a coward.” Margot goes into her tent; the two men sit and drink. Then something curious happens, the importance of which isn’t immediately evident. Wilson sees that the native servants “all knew about it”—whatever happened on the hunt—and he snaps at one of the boys in Swahili.

“What were you telling him?” Macomber asked.

“Nothing. Told him to look alive or I’d see he got about fifteen of the best.”

“What’s that? Lashes?”

“It’s quite illegal,” Wilson said. “You’re supposed to fine them.”

We may not recognize it yet, but a chink in Wilson’s armor has been exposed: his code of conduct is at variance with the law. Nothing more is made of that in the scene, but it prepares us for a more important moment that will come much later.

Then Macomber surprises Wilson. First, Francis apologizes for his poor behavior on the lion hunt. Then he says, “Maybe I can fix it up on buffalo.” Francis is climbing his way back up on the tier of honor.

If this story were about hunting—which it is not, especially—or if it were merely a kind of coming of age story—which it is, partly—it would be enough to have Francis go out on a hunt, fail, then give it another shot and succeed. But Margot’s presence—or rather, her active presence—changes everything. She returns from her tent no longer on the verge of tears.

“I’ve dropped the whole thing,” she said, sitting down at the table. “What importance is there to whether Francis is any good at killing lions? That’s not his trade. That’s Mr. Wilson’s trade. Mr. Wilson is really very impressive killing anything. You do kill anything, don’t you?”

In reply, Wilson thinks: “[American women] are the hardest in the world; the hardest, the cruelest, the most predatory and the most attractive.”

Margot says she’ll join them for the buffalo hunt: “I wouldn’t miss something like today for anything.” Her antagonism not only raises the stakes, but changes them. We understand how when finally, in a long flashback, we see the disastrous lion hunt from that morning. Francis shoots a lion in the gut, he suggests abandoning the wounded animal—a serious breach of a hunter’s code of conduct—and, when they go into the tall grass to kill it, he runs in fear. Then, after Wilson killed the lion, Margot “reached forward and put her hand on Wilson’s shoulder. He turned and she had leaned over the low seat and kissed him on the mouth. ‘Oh, I say,’ said Wilson, going redder than his natural baked color.”

Here in Hemingway’s animal kingdom, the female quickly transfers her attention to the stronger male. Up to this point, Francis’s and Margot’s strengths and weaknesses have balanced so that, Hemingway tells us, “they were known as a comparatively happily married couple…They had a sound basis for union. Margot was too beautiful for Macomber to divorce her and Macomber had too much money for Margot ever to leave him.” Macomber reflects on all of this in his tent, unable to sleep—and realizes that the other cot is empty. When Margot returns, she says she was “out to get a breath of air.” Francis grows furious, but Margot, all but purring, goes to sleep.

This scene is played almost comically, which is both entertaining and strategic. In the same way that the story is not about hunting, it is not primarily about a woman cheating on her husband. We can imagine Francis and Margot arguing late into the night, detailing each other’s shortcomings, but the scene has another purpose. Something has to happen to turn cowardly Macomber into the man who will stand his ground against a buffalo. Because Margot is all sweetness and malice, drifting off to sleep, Francis has no one to argue with, no way to vent. He is left to simmer on his cot. When dawn comes, he directs his fury at Wilson: “of all the many men he had hated, he hated Robert Wilson the most.” Seething, Macomber says, “You’re sure you wouldn’t like to stay in camp with her yourself and let me go out and hunt buffalo?”

The tension increases through suppression: no one actually yells, no one punches anyone. A shared belief in decorum acts like the lid on a pot of boiling water, refusing to let pressure escape. Margot turns up the heat:

“If you make a scene I’ll leave you, darling,” Margot said quietly.

“No you won’t.”

“You can try it and see.”

“You won’t leave me.”

“No,” she said, “I won’t leave you and you’ll behave yourself.”

“Behave myself. That’s a way to talk. Behave myself.”

“Yes. Behave yourself.”

“Why don’t you try behaving.”

“I’ve tried it so long. So very long.”

“I hate that red-faced swine,” Macomber said. “I loathe the sight of him.”

“He’s really very nice.”

“Oh, shut up,” Macomber almost shouted.

That “almost” is key—Macomber is about to erupt, but instead the car pulls up, the gun bearers get out, and they all head off to hunt buffalo. Francis is “grim and furious,” Margot is smiling, Wilson is hoping Macomber “doesn’t take a notion to blow the back of [his] head off”—a nice bit of indirect foreshadowing.

Out on the hunt, Wilson spots three old bull buffalo and instructs the driver to cut them off before they reach a swamp, which involves a jarring ride across open country. Wilson and Macomber both shoot well and are elated. Back in the car, Margot has gone pale—possibly because of the fast, bumpy ride, possibly because she slept with Wilson confident that wealthy Francis couldn’t divorce her. Now he appears fearless, and Margot realizes she may have misplayed her hand. Her power over her husband is evaporating. In the same way that Francis’s anger at Margot turned first into anger at Wilson, then into something like bravery on the hunt, Margot’s queasiness leads her to speak:

“I didn’t know you were allowed to shoot them from cars.”

“No one shot from cars,” Wilson said coldly.

“I mean chase them from cars.”

“Wouldn’t ordinarily,” Wilson says. “Seemed sporting enough…while we were doing it…Wouldn’t mention it to anyone though. It’s illegal if that’s what you mean.”

Margot, always eager to press her advantage, says, “What would happen if they heard about it in Nairobi?” “I’d lose my license for one thing,” Wilson replies. “Other unpleasantness. I’d be out of business.” In response, Francis smiles “for the first time all day” and says, “Now she has something on you.”

For a brief moment, Wilson finds himself on the bottom of the pile of this miserable little trio. Francis has proven his courage and skill, and Margot has let Wilson know that she can cause him both professional trouble and dishonor by reporting what just happened. But once again, before the story can pursue that threat directly, before the pressure can be released, the narrative takes a turn.

Hemingway creates an explicit parallel to the lion hunting fiasco: we’re told that one of the big buffalo was only wounded. This time Francis embraces the challenge. He takes his place, the buffalo charges, and Francis holds his ground, fearless—at least, until his head explodes. Still sitting in the car, Margot has taken up one of the guns and shot. The story leaves open the question of whether she was trying to shoot the buffalo to save her husband or whether she saw the opportunity to “accidentally” kill him, but Wilson expresses no doubt: “He would have left you, too,” Wilson tells her. And although he tells his men to record the details of the “accident,” while it’s clear he is not going to turn Margot in for murder, by asserting his understanding of her possible motivation and then protecting her, he has gained the upper hand.

At the end of the story, then:

- Francis is honorable, courageous, but dead;

- Margot has spent what power she has over Wilson, and lost honor; and

- Wilson is left with admiration for Francis and power over Margot.

Stories like this one remind us that to have power over someone else is to have the potential to act, as in the way Margot could report Wilson for hunting from the car, and the way Wilson could tell the authorities she shot her husband intentionally, and in the way Francis could leave his wife. They also remind us that to expend power is, often, to lose it. Once Flo persuades her husband to beat Rose, and once he does it, they have spent their power over her; once Rose yields to temptation and eats the food that Flo brings by way of apology, she loses the power of the moral high ground. When Margot threatens to leave Francis, he’s scared; when she actually cheats on him, he decides he has nothing more to lose. Similarly, when Margot makes clear that she understands Wilson has illegally hunted from the car, he has something to fear; but when she actually kills her husband, she is vulnerable again.

Hemingway’s story is dynamic not because it’s full of action—animals and people being killed, a wife cheating on her husband—but because the ways in which the three characters are revealed and judged changed, and no one’s position in the hierarchy goes unchallenged. At the end, even Wilson has been sullied by the exposure of his ethical weaknesses.

It’s worth pointing out that the crucial scenes in “Royal Beatings” and “The Short Happy Life of Francs Macomber” feature three active characters. Two characters in opposition can be in only three positions: they can be equal, the first character can have the advantage, or the second can have the advantage. Three characters multiply the possibilities, especially when different kinds of power are involved.

I realize the stories I’ve discussed here feature dramatic violence—a young girl is abused and beaten, animals are hunted, a man has his head blown off. All unpleasant. So I should reassure you that the woman I sat next to at that concert seemed to be doing just fine.

What actually happened was this: after the man put his hand on her knee, the woman used her good right hand to slap his. “Stop it,” she said. “You were angry.” And then: “That’s our Jimmy playing cello. His real instrument is oboe, but he plays cello for fun.” The woman went on to say that she didn’t like to go to Phoenix Symphony concerts because she couldn’t see well; that she didn’t live in or go to school at Marquette, but always rooted for the Big East; and that she had met Albert when, as a researcher at Bell Labs, he had been her summer intern “and we had a little fling, because that’s what you did with your interns. Fifty years later, I guess I’m stuck with him.”

What actually happened was this: after the man put his hand on her knee, the woman used her good right hand to slap his. “Stop it,” she said. “You were angry.” And then: “That’s our Jimmy playing cello. His real instrument is oboe, but he plays cello for fun.” The woman went on to say that she didn’t like to go to Phoenix Symphony concerts because she couldn’t see well; that she didn’t live in or go to school at Marquette, but always rooted for the Big East; and that she had met Albert when, as a researcher at Bell Labs, he had been her summer intern “and we had a little fling, because that’s what you did with your interns. Fifty years later, I guess I’m stuck with him.”

The narrative I had imagined turned out not to be true—but several new possibilities had been revealed. And if my telling of the tale here seems a bit manipulative, let that be a reminder of another power play: the power of the storyteller, always arranging information to suit his own ends.