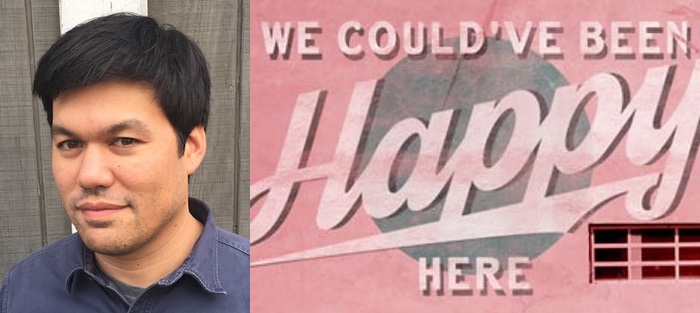

If you’ve been reading any number of literary magazines the past five years, you’ve no doubt come across some stunning work by Keith Lesmeister. Starting with his first publication in 2012—the short story “Loony Bin,” published in Midwestern Gothic—Lesmeister has been exceptionally busy writing, publishing, and becoming an author whose impressive body of work creeps up on you like an early autumn frost. Since that first story five years ago, Lesmeister has published more than 30 other works of short fiction, in esteemed journals like American Short Fiction, Gettysburg Review, Meridian, Slice, Redivider, and the North American Review, among many, many others. But he’s been busy with so much more.

Along with his dedication to the art of short fiction, Lesmeister has focused on building a wonderfully revealing set of essays and short memoir pieces in places like River Teeth, Sycamore Review, and the Tin House Open Bar, and he’s explored the impact of emerging authors’ stories in Life as a Shorty, a literary blog that touches on the craft and technique behind the works, and which frequently showcases interviews with the authors themselves. Combine this with the fact that he teaches full time at Northeast Iowa Community College, and it’s any wonder that Lesmeister’s found time to rev up a book tour through middle America.

This May, the editors who first published Lesmeister’s short fiction are also releasing his outstanding debut story collection, We Could’ve Been Happy Here. The group’s book imprint, Midwestern Gothic Press (which, like the original journal, was founded by Michigan-based James Pfaller and Robert James Russell), showcases “the very best in Midwestern writing” by writers either living in the region or whose work has been inspired by their time there, and the release of Lesmeister’s story collection is a perfect example of just how important the publishing group’s work is.

A few months ago, I was fortunate enough to catch up with Keith at the annual AWP conference in Washington, D.C., and again in the middle of his book tour in April. We chatted on the phone and online after our children had gone to sleep for the night, pausing only to check up on the occasional sound in the nighttime.

Interview:

Barrett Bowlin: You’ve been absolutely prolific since 2012, man. How in the world do you find time to write? For that matter, what’s your writing schedule like?

Keith Lesmeister: It’s no coincidence that 2012 was also the year I started my grad school program. Let me also say this: I wasn’t teaching in 2012. I was working an administrative (8 a.m.–5 p.m.) role at the college, and that allowed me a lot of time both in the mornings and evenings to write. From 2012–2014, the years I was in grad school, I wrote everyday for at least an hour. And—to be honest, I think this was the best part—I was also reading everyday for at least an hour. The two informed each other in ways that I wasn’t expecting. Sheer output being one of them. On top of all that, I had monthly deadlines. Talk about a motivator. Now, with teaching, hell, I feel like I’m working all the time, and the writing is starting to take a backseat role. So to your question: when do I write? Whenever I have 20–30 minutes free, I’m writing.

That is some solid discipline, no joke. For your grad school program at Bennington, you mentioned the monthly deadlines. What were the big tools you picked up from the program there? (And I’m talking in terms of reading, writing, discipline, structure, etc., or anything else that stands out.)

When I first started at Bennington, I really felt brand new to writing. And one of the reasons I chose the program—in addition to their excellent faculty and beautiful location—was their emphasis on reading. There were major gaps in my reading, and I wanted that to be a focus. In terms of tools I picked up while attending, like I said, I felt pretty new to writing upon entering grad school, so everything I learned felt so hyper-important, and it was. I learned how to write scenes (get in, get out), dialogue, and where/how to start a story, and the list goes on and on. I had excellent faculty mentors—David Gates, Bret Anthony Johnston, Amy Hempel, and Wesley Brown—and each challenged and pushed me in ways that really helped my writing, and gave me reading suggestions to help inform my work. But I think the reading was what really helped my writing, at least in the longer term.

Before the MFA, I attended the Iowa Summer Writing Festival where I worked with a great writer and just an all-around great guy, Andrew Porter. He was one of my earliest encouragers. In fact, he was the one who told me about low-res MFA programs. I didn’t want to up and quit my job and move, especially with kids and a full-time job, so the low-res option was perfect. During the actual MFA, I learned so much from each teacher. It’s tough to tease out one or two things, but let me try: David Gates taught me how to edit my own work, and Bret Anthony Johnston and Amy Hempel taught me how to find the “heart” of the story, which has to do with finding a character’s true desire and motivation.

Along those lines—and this gets us into the story collection, as well—I have to say that there’s such a strong, clear voice in each of the stories in We Could’ve Been Happy Here. It’s a confident voice, not afraid of spending time in a character’s head and letting them build up problems and figuring their way out or through. So I’m curious: who were some of the authors you had to read in order to develop that voice?

Along those lines—and this gets us into the story collection, as well—I have to say that there’s such a strong, clear voice in each of the stories in We Could’ve Been Happy Here. It’s a confident voice, not afraid of spending time in a character’s head and letting them build up problems and figuring their way out or through. So I’m curious: who were some of the authors you had to read in order to develop that voice?

There are so many. When I was writing this collection, and even before writing it, I was enamored with several authors: Lorrie Moore, Ron Rash, Chris Offutt, Brad Watson, Mary Miller, Elizabeth McCracken, Denis Johnson, Charles D’Ambrosio, and the list goes on. Each has their own distinct style, certainly, and they also have a beautiful mix of poignancy and levity, at times. I love that, and each, in their own way, along with dozens of writers not mentioned here, have influenced my work greatly, not to mention the work of my former teachers.

Were there any Midwest-specific authors who helped you figure out how to write these stories that focus on the “rural”? (And I say that last part in quotes because I don’t want to pen your entire body of work into that adjective.)

I appreciate that word in quotes, and yet it’s true: most of my stories are set in the rural Midwest or on the edges of town. Denis Johnson’s collection [Jesus’ Son] takes place in and around Iowa City, for obvious reasons. He spent a good deal of time there. The others write extensively about rural locales. Take Ron Rash, for example, or Chris Offutt. I guess there weren’t any Midwest-specific folks I was reading at the time, but since writing the collection, I’ve been reading and rereading Jane Smiley. A lot of her work is set in rural Iowa, and the way she slowly and timely reveals character is so perfect up against the slow-paced life of an Iowan countryside. There’s a kind of patience that she demands of her reader, in the same way there’s a kind of patience in watching the landscape change through seasons, or the patience one might need while driving from one small town to the next while getting stuck behind a combine that’s moving from one field to the next.

Let’s get into some details and talk about Midwestern Gothic. How did you come across the journal? And aside from the regional overlap, what made their adjoining book publishing imprint, Midwestern Gothic Press, a good fit for your collection?

They published my very first story, and it does feel appropriate that they are also publishing my first collection. I really don’t remember how I found them, but I do remember thinking how great of a fit they would be for my work, and sure enough. In terms of my collection, MG Press publishes Midwest authors who write specifically about the Midwest. Their guidelines for MG Press are a bit more stringent than the journal, which publishes anyone with any connection, however loose, to the region. But my collection fits on all fronts. Plus, Jeff and Rob and the team at MG Press are just super fantastic to work with, and their laid-back style of enthusiasm was something I was drawn to right away.

Digging into We Could’ve Been Happy Here, there are, of course, lots of threads that tie the stories in the collection together. But what would you say is the overarching connective tissue in the works?

I really didn’t have a clue what the overarching connective tissue might be outside of what we’ve already discussed, which is the setting, Iowa. But after putting the stories together and sitting with them a while, I think there are lots of things connecting the stories, not least is the motivation for writing each story, which all have some element of twisting the commonly understood writing advice: write what you know. In all of these stories, I’m trying to write what I don’t know. For instance, in the first story, a man is farm-sitting for a friend. He’s chasing down two rogue dairy cows while contemplating ways of getting his estranged family back; or, there’s the second story about a young guy who carts around his suicidal grandmother while getting drunk on screwdrivers. Part of the joy in writing these stories was allowing the characters to take over and make decisions that were wholly their own. That’s one of the wonderful things about writing what you don’t know. There seems to be more room for that element of surprise and discovery, which is like striking gold for a fiction writer.

I guess what I meant to ask is: what was the connectivity you saw in these particular stories that made you choose to put them together into a collection? Take your story “Ice Silo,” for example. It was written during the same time period, it focuses on an Iowa scene in winter, but you made the decision not to include it in the collection. Out of all the stories you’ve written and published, what made these twelve stand out to you? What connected them in particular?

So I always knew the two Vincent stories [“Nothing Prettier Than This” and the title story] would work as bookends. Outside of that, I thought about the stories synchronizing tonally. Which is to say, I wasn’t thinking of subject matter or themes as much as I was thinking of the sound quality of each—upbeat, somber, humorous, longing, etc. Another example: I always knew “Today You’re Calling Me Lou” would be one of the first stories because it’s fast-paced, feisty, and gets things moving (or at least I hope that’s the case).

And on a side note, I would like to include some of the others stories in another collection, perhaps down the road at some point.

The stories in WCBHH go far back as Winter 2014 (“Today You’re Calling Me Lou”) to, most recently, this past winter of 2017 (“Lie Here Next to Me”). Over this stretch of three years, what would you say have been your obsessions? What’s been holding your attention, and what of that would you say has been showing up in your work?

I’m not sure how to articulate this, other than to say raw, naked vulnerability. I want to see people—characters—in their most vulnerable states and how they deal with others and themselves in that stripped down state.

So in terms of plotting out a story line, would you say you like to throw characters into situations and see how they respond, or do you normally have your endings and resolutions in mind beforehand?

Definitely the former. I always start with situations—complicated, messy, unwieldy—and wait for my character(s) to say or do something. Once that happens—that action or piece of dialogue—we’re off to the races. Endings are difficult, but they usually reveal themselves at just the right moment, which comes after hours of spending time with that character.

I like that sense of connection. Okay, one last question: now that the collection is coming out, what’s your next project? How do you want it to differ from the stories in WCBHH?

I love reading and writing short stories, and that is still what I’m doing—what I’m working on—and what I’ll continue to work on for the time being. In terms of differing from WCBHH? I don’t think I’m far enough along to answer that question.