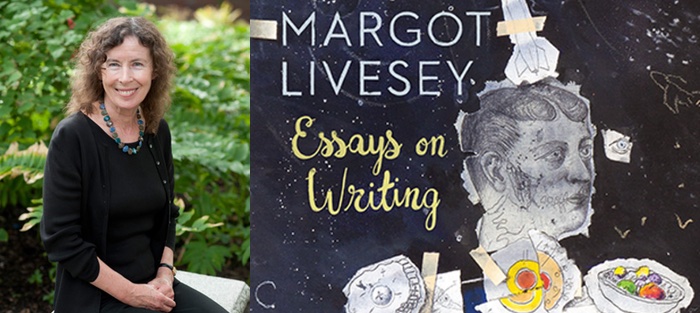

I first met Margot Livesey in 2008, when she led my workshop at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. As a newer writer, I was uncertain about my place at that vaunted literary gathering and dazzled by the many brilliant authors in attendance. When Margot and I met to discuss my work, her kindness and the precision of her comments (offered in that enchanting Scottish accent) put me at ease—I’d been so nervous to show my pages to the author of Eva Moves the Furniture and Banishing Verona, two novels I’d read and marveled over before the conference. That summer afternoon, as we sat in the shade of a cool patio, Margot carefully went through my work line by line—the pages that would become the first chapter of my first novel—reading aloud and breaking away often to comment on a missed opportunity, or a moment of wobbly character action, or a line that just didn’t ring true. I often tell people that that hour of conversation was the MFA I’d never received. While her notes on my work were the reason for our meeting, what I took away was even more invaluable: the chance to witness in real time how a remarkable novelist reads and considers fiction in progress in order to make it better, and to build belief.

In her generous and far-ranging new collection, The Hidden Machinery: Essays on Writing (Tin House Books), Margot Livesey recounts a formative learning moment of her own, when as a new writer she brought draft after draft of a short story to the Irish novelist Brian Moore, then visiting a university near the restaurant where she was working as a waitress. As he read her drafts aloud, he pondered the details in each line, questioning and guiding Livesey toward an improved version. As she writes, “He showed me that a good sentence speaks even to its own maker and that we often recognize our own mediocrity, even when we pretend not to.”

This experience of wisdom passed down over time, writer to writer, suffuses The Hidden Machinery, which takes as a premise that great novels themselves, and the stories of how they came into being, are our best teachers. As Livesey describes in our interview she views her collection as a “companion” for readers of all kinds. And part of the joy of this book is how deeply invested in reading it is. From Jane Austen and Shakespeare to Hanya Yanagihara and David Wroblewski, Margot Livesey looks closely at language, structure, and style in order to pinpoint useful and specific lessons for writers and their own stories. By reminding us of works we’ve loved for years as well as introducing us to titles we now know we need to search out, The Hidden Machinery transcends the category of writing handbook to become an invaluable guide to that larger world of literature and its inner workings.

Margot Livesey’s other books include the novels The Flight of Gemma Hardy, The House on Fortune Street, The Missing World, Criminals, and Homework, as well as the collection of stories Learning by Heart. She’s received awards from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. Our conversation here ranged over the process of writing her most recent novel (Mercury, published by HarperCollins in 2016) to her many years as a teacher of creative writing, currently at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. In our correspondence about books and writing, I find evidence of a life devoted to the love of fiction as well as to its crafting. Both writers and readers have much to be grateful for in The Hidden Machinery.

Interview:

Emily Gray Tedrowe: The subtitle of The Hidden Machinery (both a title and concept I love, by the way) is “Essays on Writing.” It strikes me that these essays are as much about the writing process as it occurred for the authors of some of literature’s greatest novels—Woolf, Austen, Flaubert—as they are “how to write” suggestions for writers of the present. Can writers today find inspiration in the early drafts of these masters as well as letters or journals that have come down to us over the years?

Margot Livesey: The word inspiration comes from the Latin to breathe upon, or into, and I do think that reading the work of our forebears and reading what they said about writing, can breathe new life into my work. When I discover that Woolf knew she had to wait for To The Lighthouse to thicken, or that Austen revised the famous proposal scene in Persuasion, I am heartened by the knowledge that these beautiful books did not spring onto the page without effort. As I worked on Mercury these novels, and many others, reminded me of how much minor characters can do both to reveal the main character and advance the plot.

An aspect of this collection I am grateful for is your generous inclusion of your own struggles with writing, for example the way you describe difficulty with character development (or as you put it, being “character handicapped”) and how you’ve worked on this. How important is it to you to share those moments, and is that hard to do?

An aspect of this collection I am grateful for is your generous inclusion of your own struggles with writing, for example the way you describe difficulty with character development (or as you put it, being “character handicapped”) and how you’ve worked on this. How important is it to you to share those moments, and is that hard to do?

As a fiction writer I am used to hiding behind the word “I,” so one of the things I had to figure out in The Hidden Machinery was how to inhabit the first person in a different way. What was my voice going to be as a nonfiction writer? It helped that many of the essays grew out of talks or lectures where I had a clear sense of my audience. As someone who came to fiction slowly and awkwardly, through many failures, I am always glad to be reminded that writing fiction is a craft that most of us learn painstakingly, story by story, novel by novel.

Several times in these essays you refer to “rules” you’ve set for yourself in writing projects. For example, in your discussion of how to create individualized dialogue patterns for different characters, you write “In my novel Criminals I had a private rule that no two characters could use the same swear words.” What can private rules do for fiction writers while they are drafting new work? Are there any other rules you’ve used for your novels or stories?

I only wish there were more rules for writing a novel or story, like there are for a sonnet. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? I do try to come up with my own private rules. In my novel Banishing Verona one of my two protagonists has Asperger’s and being faithful to his experience of the world provided a very interesting set of rules. More recently, in Mercury, I had to be sure that Viv thought and spoke American English. And that her love of horses, her belief that they are an absolute good, was unquestioning. Maybe it’s the aftermath of my strict Scottish childhood that has left me with a sense of rules as enabling.

In the essay “Neither A Borrower Nor a Lender Be,” you argue against Polonius’s famous advice by exploring the nature of homage in fiction, and its pleasures. Your own novel The Flight of Gemma Hardy is a “reimagining” of Bronte’s Jane Eyre. Is part of the desire to “be in conversation” with previous books the fact that writers come to literature first as readers? Is “homage” perhaps our belated desire to display great love for novels that shaped us?

Yes! I fell in love with Jane Eyre when I was the same age as Jane and many of the events in her life are more real to me than events in my own. I wanted to testify to that love, and to explore some of the strengths of the novel including how memorable it is. Also, as someone who lost her parents at an early age, I am probably even more susceptible to orphan stories than most readers; I relished the idea of exploring this form.

I loved the many lists that pepper The Hidden Machinery. Lists of rules for romances, lists of questions to generate motivation, lists of distilled wisdom for writers from Shakespeare’s work. Do you also use lists when you’re working on your fiction, or for teaching?

I do in my teaching although I always include the caveat that whatever list I’m offering is partial and can be ignored, or flagrantly contradicted. E.M. Forster in Aspects of the Novel describes admiringly how Dickens can bounce his readers into belief and I think that’s true. Rules are only useful if they help to get that energy on the page.

I wanted to ask about how your thoughts about writing in this collection dovetail with your recent novel Mercury. Did any of these craft elements play a particular role when you were writing? How conscious are you of using what you know about fiction when you sit down to write it?

For me, and perhaps for most writers, there are several stages to writing, some more conscious than others. In the initial stages, as I try to get material on the page, I am usually not thinking about the craft elements as much as I should be. When I began Mercury I had a clear sense of the occasion of the novel: a woman falls in love with an amazing horse and ends up buying a gun. But it took me a while to figure out how to create my two main characters—Donald, the myopic husband, and Viv, the horse lover—and I did find myself going back to my essay about character: “Mrs. Turpin Reads the Stars.” I needed to be reminded about the importance of creating and conveying a character’s attitude. And looking at “He Liked Custard” stopped me from falling down the rabbit hole of research.

There’s a wonderful moment in The Hidden Machinery where you recount studying with the Irish novelist Brian Moore, and how he read drafts of one of your stories aloud each week, making comments line by line, and showing you by example how to read and revise your own work. I imagine you see that moment with particular interest now, having taught creative writing for many years. You can’t possibly have time to read each of your student’s drafts aloud in that way. But is it a method you encourage them to use on their own?

My admiration for Mr. Moore’s generosity increases with every year. How did he do it? But I do remind myself that he was not actually teaching a class; he was a writer in residence at the University of Toronto and no one else seemed interested in meeting with him. Alas, I don’t have time to read my students’ work aloud to them but I do urge them to use this invaluable method of discovering where the prose is flagging, where the story is going astray.

What do you make of the state of creative writing programs in our universities and graduate schools? What “level” of writer were you thinking about when you wrote the essays in The Hidden Machinery?

I feel far from qualified to make global comments about creative writing but I think it’s clear, from looking at enrollment in classes and writers’ conferences that many people are interested in writing, and many voices, not previously in the canon, are now being heard. Academia has become the main patron of writers but there are still a goodly number of writers working outside universities. Publishing and reviewing have their vicissitudes—so many books, so little review space—but I am heartened by the burgeoning number of small presses, magazines and sites like this one.

When I wrote The Hidden Machinery—a book that assembled over many years—I was thinking about both readers and writers, both those in classrooms and those at home, or in book clubs. I wanted to write a book that would make the reader feel accompanied in the way that I feel accompanied by the novels and stories I love.

I found myself making a “to read” list as I went through The Hidden Machinery—as well as a “to re-read” list, and that’s been one of my favorite things about this book. What fiction have you read recently, new or old, that has brought you pleasure or been significant for your work?

I read Rachel Kadish’s new novel The Weight of Ink with great admiration. It’s both a literary mystery and a wonderful account of the Jewish community in seventeenth-century London. I’m currently reading Eudora Welty’s The Optimist’s Daughter with amazement: how does she do it? I love the way her characters say the most surprising things. And I am looking forward to two collections: Amina Gautier’s The Loss of All Lost Things and Mia Alvar’s In The Country.

Are you working on a new novel yet (she asks hopefully)? What’s next for you?

Thank you for asking. I am at work on a new novel. It’s in the early stages but I am hoping to bear down on it this autumn, and to make good use of the wisdom and example of other writers.