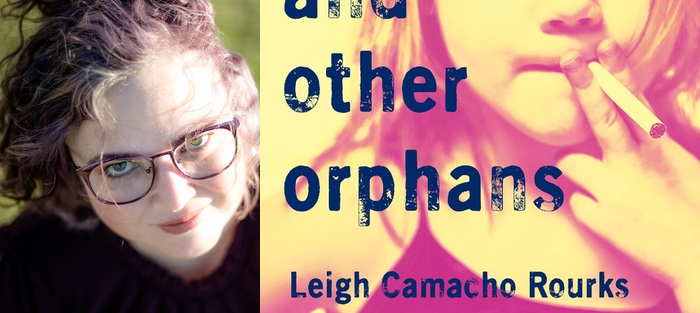

A longtime friend and fan, I was super excited to learn of Leigh Camacho Rourks’ debut, Moon Trees and Other Orphans (Black Lawrence Press). There is much to admire in this collection. Her depictions of rural and working-class life in Southern Louisiana are punctuated by her portrayals of intensely complex, superbly flawed characters making their way through the world they’ve been given, oftentimes learning hard lessons and just as often not learning them. I would happily describe Leigh as a writer who revels in taking risks. One might think that a collection filled with so much violence and so many guns and drugs would be trafficking in the sort of shock and titillation we often find in stories that approach these themes. But this is not the case with Leigh, because at the center of each and every one of these stories is a beating heart that we all can connect with.

Leigh Camacho Rourks is a Cuban-American author who lives and works in Central Florida, where she is an Assistant Professor of English and Humanities at Beacon College. She is the recipient of the St. Lawrence Book Award, the Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner Award, and the Robert Watson Literary Review Prize. Her fiction, poems, and essays have appeared in a number of journals, including Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, RHINO, TriQuarterly, December Magazine, and Greensboro Review.

Interview:

Saul Lemerond: There are several themes that run through the stories in this collection. The natural world—especially as it relates to Louisiana—violence, and probably most importantly, the body. You use a lot of embodied descriptions: descriptions of the body, the body moving in space, and bodies as they’re perceived by other people. Has this always been a focus for you, and how has this interest in the body as a theme, and of the other themes, evolved for you as a writer over time?

Leigh Camacho Rourks:I don’t know that those themes evolved for me as a writer. Perhaps they are things that have evolved for me as a human. I think that you write about the problems you’re solving, the things you’re curious about, and the things you notice in this world that you’re interested in. Those are probably all themes that are in my life that I’ve been generally attuned to or have always thought about. The body in space, for example. That’s something that I’ve been interested in for as long as I can remember. I was a dancer when I was young, but I became a dancer in sort of a strange way. My asthma was undiagnosed as a kid, so I was no good at PE. I couldn’t do it. And my PE teacher was like, “Oh, well, maybe you could be a dancer.” So, I went to this magnet school for dance and I sucked at it. I got in because at the audition my teacher saw tears streaming down my face as I tried to do what I was asked to do. She was so impressed by my deep desire to actually do it (not my ability) that she let me into the program. So I’ve always had a clumsy body, but a body that I’ve had a lot of desire to have very strict control over.

You also put quite a bit of focus on your characters’understanding of their bodies as sexual. I feel like this is especially true for Maggie in “The Revival.”

That’s a particularly lurid story. It may come as a surprise, but I’m very weird about writing sex. I’m not squeamish talking about it, but I’m squeamish writing directly about the act itself. On the other hand, I’m very comfortable writing about the body as sexual. We are sexual beings, maybe more than anything else, and of course, there is so much more to sex than the act, so many ways for a person to be sexual, to perform sexuality, to obsess over sex. Or, as Maggie does, to use sex to exert and feel control. That’s one of the most fascinating things about sex, its power over us.

And this is what resonates with the reader?

Yes, sex is a form of power and control in the real world. In many ways, being a girl was to grow up feeling powerless and being told that you are powerless. Tangled in that lesson was a constant awareness of the threat of rape and assault, of sex itself being presented as an ever-present threat, the ultimate display of violent power against a woman. In “The Revival,” Maggie has internalized that concept of sex as a weapon and has stolen it for herself. Like many people who’ve suffered childhood trauma and abandonment, her emotional growth is stunted and her understanding of autonomy, power, and sex is tangled up. But that isn’t a tragedy. Instead, it has been the key to her survival. She has upended the idea that she exists purely to be used, and through that keen awareness of her own sexualized body that you mention, she usurped the power others would wish to have against her.

Yes, sex is a form of power and control in the real world. In many ways, being a girl was to grow up feeling powerless and being told that you are powerless. Tangled in that lesson was a constant awareness of the threat of rape and assault, of sex itself being presented as an ever-present threat, the ultimate display of violent power against a woman. In “The Revival,” Maggie has internalized that concept of sex as a weapon and has stolen it for herself. Like many people who’ve suffered childhood trauma and abandonment, her emotional growth is stunted and her understanding of autonomy, power, and sex is tangled up. But that isn’t a tragedy. Instead, it has been the key to her survival. She has upended the idea that she exists purely to be used, and through that keen awareness of her own sexualized body that you mention, she usurped the power others would wish to have against her.

I feel like this can be connected to violence, which is another theme that permeates your work.

I’ll probably never stop writing about violence. I’m not sure I know how to write about things that aren’t violent, which seems an absurd statement, but for one reason or another it is the lens through which I perceive the world. Violence is the physical manifestation of our most extreme emotions, of fear and anger and desperation and loss and even of positive emotions like hope—emotions that tie us to the things and people we are willing to fight for. It is one reason that many of us who grew up as members of the working class so keenly understand the language of violence. Even if we are not physically violent ourselves, the violence of those emotions is exasperated by feelings of need. I am trying to learn how to not write just violence, but at the same time I’m not super interested in completely leaving that behind.

That actually connects with another one of my questions, which has to do with why you write so much about the working class and the working poor. Is it just because that’s what you grew up with, so you find it more interesting?

Instinctually, yes. I started writing about it because that’s what I grew up with. Those were all my friends. I’ve never had bougie friends. There is also the fact that I get mad that “literary” literature is always about these people who I can’t identify with. People in New York who are just so tired of being rich or whatever, and I cannot stand it. I can’t identify with it, and it bores me. Also, I get really annoyed with how lower class southern people of every ethnicity and race are constantly portrayed as being illiterate when most rural people are huge readers, for example. So, part of the reason I write about working class people is because I’m angry.

Do you also have a desire for people who enjoy reading that sort of New York stuff to read your stories, so they have better understanding of places that aren’t usually thought of as the cultural centers of America?

I don’t know if I care about the people who choose to read that sort of stuff because they predominately see themselves in it, but I do definitely care about the people who read that stuff because they think it’s all there is. A lot of readers read that stuff because that’s what they’ve been told is good writing. It’s like when everybody was watching Seinfeld. I’m not putting down Seinfeld, I like Seinfeld. What I’m saying is we watched it because that’s what all the shows were about, not because everyone watching identified with these New York people complaining in their apartment. And, I think that’s changing. Grit Lit is getting really big. There are so many great authors showing us the world outside of posh cities, and they have been doing it for a while. Bonnie Jo Campbell, who I had the great fortune to study under, is a good example of this. So are Tom Franklin, Dorthy Allison, Jesmyn Ward, Wiley Cash, and Nic Pizzolatto. It’s a really rich genre.

And yet despite similarities in class, many of the characters in the book are quite diverse in other ways. Can you talk about how identity factors into your work?

I was born in South Lousiana, but lived most of my childhood in Florida. We were there until Hurricane Andrew, which destroyed our house when I was seventeen, after which my family returned to Louisiana. Both are incredibly diverse places. Where I grew up—and when I grew up—I was considered mixed. I’m not really anymore. I’m half Cuban, but I’m white Cuban, which gives me certain privileges. But, the inequalities of race and ethnicity and just the things that I would hear people say—I’ve been acutely aware of the danger of difference my whole life. It’s a tough topic. I’m constantly ready to go into a rage. I haven’t grown out of that. I think that’s why I write diverse characters, but it’s also because I have never lived in an all white place. I don’t even know what that looks like. So, again, I think it would be weird for me to write that. That would be an absurd situation. To me that’s absurdism.

I was born in South Lousiana, but lived most of my childhood in Florida. We were there until Hurricane Andrew, which destroyed our house when I was seventeen, after which my family returned to Louisiana. Both are incredibly diverse places. Where I grew up—and when I grew up—I was considered mixed. I’m not really anymore. I’m half Cuban, but I’m white Cuban, which gives me certain privileges. But, the inequalities of race and ethnicity and just the things that I would hear people say—I’ve been acutely aware of the danger of difference my whole life. It’s a tough topic. I’m constantly ready to go into a rage. I haven’t grown out of that. I think that’s why I write diverse characters, but it’s also because I have never lived in an all white place. I don’t even know what that looks like. So, again, I think it would be weird for me to write that. That would be an absurd situation. To me that’s absurdism.

What would be absurd?

That there’s a place where everyone—everyone—is white. WASPS. It sounds like some kind of strange, future horror movie. I know it’s not, intellectually, of course. It’s sort of like how I feel about temperatures below zero. Obviously, there are places where it’s colder than zero, or where everyone is white, but those facts don’t feel real to me.

So, you often talk about how important it is to put heart in your stories. For this collection, I feel like you end every story with a pretty dramatic emotional transition. For most of the stories, this transition happens in the character, which is then reflected in the reader. What is the heart, how do you put it in, and did you used to think about it differently than you do now?

One of my teachers, Jack Driscoll, said you gotta love your characters. No matter what bad things they do. I became a better writer when I started to do that. I think what makes heart is taking whoever you are and doing the one thing you don’t like to do, which is cut yourself open, take a piece of you, grab it, and put it on the outside. And not be sarcastic and not make a joke out of it. I think doing that on the page is when you have heart. For me, the endings of the stories are when all of that comes to a head in some sort of an emotional break or transition. That’s the moment in life I’m most interested in. A lot of people say, “That’s where you ended it? Why end it there?” I think that for me it’s the end of the story because once the emotional break happens, I’ve gotten at the thing I’m most interested in. I’m all hard edges. I don’t necessarily like all that squishy stuff. I think finding that squishy stuff in characters that are all hard edges and then showing that on the page is what heart is.

Are you always striving to make that emotional transition happen in the characters, or are you sometimes actively trying to ignite the emotions of just the reader?

Not intentionally. Do you have an example?

I think you can make an argument for “Pinched Magnolias,” the story where Dalia guns down her ex-husband, Bud, and then calls up her sister to help bury him in the bayou. It ends on a bit of a twist.

So that story is a little complicated because in some ways that story is earnest in its telling. But it’s also taking all the Southern Gothic tropes and pulling at them in the ways satire or parody might. I didn’t write that story knowing the “twist” ending, the violence Dalia has suppressed, so that was a discovery for me. But in a sense it’s a discovery for her too. What I mean is she took the thing that happened and put it in a box. She didn’t forget, exactly. You know there are things that you’ve done that are bad, bad things, and it’s not like you have amnesia, or you have blocked memory, but you certainly don’t deal with them. The emotional thing for her is she had to deal with this horrible, suppressed fact in that moment. But, yeah, that emotional turn, that experience is for us to experience, too.

Maybe there’s some of this in “The Revival,” too, in which Maggie and her boyfriend, Bouie, go from parish to parish running a Baptist tent revival con. There’s a love triangle there. Maggiegoes through quite a bit. She has a big problem, but she wins, which is pretty great.

Maybe there’s some of this in “The Revival,” too, in which Maggie and her boyfriend, Bouie, go from parish to parish running a Baptist tent revival con. There’s a love triangle there. Maggiegoes through quite a bit. She has a big problem, but she wins, which is pretty great.

But she loses too, right? It’s a terrible loss, as well. She doesn’t mean it to go that way. She’s shocked by it, but she’s a survivor so she’s going to win either way. Maggie is a terrible person, and readers hate her. That’s a good example of the idea that you’ve gotta love your characters. I don’t hate her. I love her. In many ways that story is me at my most vulnerable. I know that sounds terrible.

I don’t know. I like Maggie.

I don’t hate Maggie, people hate Maggie.

You’ve also told me that people get mad that Karo shoots an endangered bird in “The Shallowing.” It didn’t bother me because, you know, no birds were harmed in the writing of that story.

Oh, yeah, no birds were harmed. And as you know I’m like an obsessive animal lover. You’ve seen me cry because there was a dead animal on the side of the road.

To me, that story is more about what the shooting of the bird represents. Why does she shoot it? That’s the interesting question. I think some people read stories because they really want to connect and empathize with characters and go on their journey with them. And some people read stories because they want to learn something about the human condition.

Right, but here’s my deal: I want you to connect and empathize with those people. I want you to understand that you are capable of horrible things even if you’re a good person. Or, if you’re a bad person, you’re capable of great and beautiful things. So get in there, fall in love with Karo, feel for her, feel like she’s like you, and then shoot that bird with her. I think that’s why people get mad. What they saw in themselves turned out to be horrible. Ultimately, that’s the important thing. You should know that you can love horrible things, and you might be a horrible thing one day.

I like that. I mean, I don’t like that she’s lying to her father. He seems like such a good person.

Such a good guy, right?

I understand that’s the whole point. It makes me think of Sal Paradise from On the Road. People love him, and he’s sort of a piece of shit. I don’t know if it’s sexism, or maybe it’s just the feelings of wanderlust in the people who like to read him, but…

Yeah, people are much more comfortable with a piece of shit man than a piece of shit woman. Here’s the problem with writing a piece of shit woman, which I do a lot: there aren’t enough women characters. In some ways if you write an unlikable woman, you are representing womanhood. But if you write an unlikable man, he doesn’t represent men. He’s just a guy who’s unlikable. That’s a really unfair tokenized burden to put on female characters. Like I’m supposed to be uplifting all women with my characters.

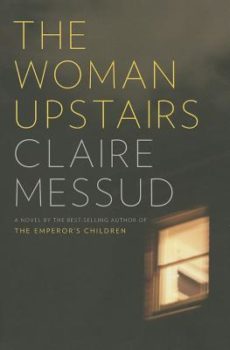

When Claire Messud was interviewed in Publishers’ Weekly about her main character’s unlikableness in her novel The Woman Upstairs, her—now famous—answer was that this was a ridiculous question, that we don’t expect to want to be friends with male protagonists—and she listed a litany of bad guy male characters. She said, “The relevant question isn’t ‘is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘is this character alive?’” The problem is that one way women have been marginalized is by stripping them—stripping us—of a full range of emotions, motivations, and reactions. And this is done by both men and women. It is often done in the guise of empowerment or compliment. “Women are kinder,” we say. “Nurturing, thoughtful.” This is limiting, though. To be human is to have all of the potential positive and negative attributes that come with being human. When we ask that allfemale characters uplift allof womanhood, what we are saying is that womanhood is a homogeneous block. That’s not being alive. And those qualities I am supposed to embody simply because of my genitalia—that goodness and nurturing gentility—I don’t, and my characters don’t either.

When Claire Messud was interviewed in Publishers’ Weekly about her main character’s unlikableness in her novel The Woman Upstairs, her—now famous—answer was that this was a ridiculous question, that we don’t expect to want to be friends with male protagonists—and she listed a litany of bad guy male characters. She said, “The relevant question isn’t ‘is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘is this character alive?’” The problem is that one way women have been marginalized is by stripping them—stripping us—of a full range of emotions, motivations, and reactions. And this is done by both men and women. It is often done in the guise of empowerment or compliment. “Women are kinder,” we say. “Nurturing, thoughtful.” This is limiting, though. To be human is to have all of the potential positive and negative attributes that come with being human. When we ask that allfemale characters uplift allof womanhood, what we are saying is that womanhood is a homogeneous block. That’s not being alive. And those qualities I am supposed to embody simply because of my genitalia—that goodness and nurturing gentility—I don’t, and my characters don’t either.

Let’s shift to language. I want to talk about your sentences. I know you, so I know you take great time and care with each sentence you write. When do you fall in love with the sentence, and why is it so important to you?

Too much probably. I’m not fastidious about much. But when I become obsessed with something, I become very obsessed. I write out loud. Crafting a sentence is a joyous thing for me. I’m not a writer who’s driven to write. I’m not a writer who’s going to go around and talk about how much she loves to write. Mostly it’s hard. Not roofing hard—there are things way harder in this world—but, dude, I can spend all day crafting one sentence. It’s fun.

When you say, “write out loud,” what do you mean?

I mean living with me is hell. I have to say it all over and over and over again. I can speak it in my head the first few times, but I can’t go further until I say it out loud. I have to actually hear it. If it doesn’t sound right, I can’t move forward. I’m not OCD, I’m not going to claim that I am, but sometimes I get stuck and I can’t do another thing until the sentence feels right. Doesn’t mean it will be right when I go back to revise, but I can’t even conceive of going further until I get it clicked.

Every sentence that has ever been written in a story that’s ever been published—and a bunch that haven’t—has been read out loud multiple times in first draft. And people are like, “Well you can’t do that. You have to just write, and then you’ll fix it later.” I can’t. It gives me anxiety to think about doing that. I really thought I was a bad writer. I really stressed about it, but I just can’t. It’s like I have to tap the toilet three times if I use the bathroom in the middle of the night or I’m afraid I’ll pee the bed. I can’t not do it. Reading my sentences aloud until they sound right is something I have to do.

Is revision a similar process?

I go back before I go forward, always. Everybody says not to, and I don’t know if that’s good advice. Studies have shown that recursive reading and writing is a natural habit for a lot of good writers and readers. I’m also layering. Over the years, I’ve learned where my problem areas and strengths are. So, I keep those in the back of my head. For example, I used to really suck at setting because I just wanted to write dialogue. I’m much more interested in people. So first I had to learn that setting was a part of people. Together they become place. Once I understood what place was, I got better at it. Still, I add. I write and then I go back and look for where I left something out. Then I start to add it. And then what I’m looking for at the same time is, What are some images that can become tropes? I don’t really think about theme very much because it just happens sort of naturally. I can’t escape the things I’m obsessed with. They’re going to be there. But the images. It starts when you get an image, and it’s a good image. Then you’re like, Does this image need to reverberate? It’s already resonating. Can I tighten that resonance? Then you go in, and you start to layer.

Can you think of an example from this collection that this applies to?

“Clown” is a good example. It has all these bird images. There’s a lot of flapping. There are birds all over. Originally there were only two bird images. But, then there’s that point the narrator makes about how birds don’t necessarily mate for life. That’s the point where I understood her better. She was lonely. She wanted to love somebody, but she doesn’t really know if that’s possible. And, there’s a dead crane, and I’m like, Well, that’s important. There was also a bird with the little girl, and I’m like, Well, that’s important. Obviously, I like what those images are doing. So how do I make this resonate throughout the story in a way that it’s not annoying, but where the image definitely reverberates? It’s not like there’s a moment when I’m thinking, This is a trope, and I am going to put it in seven more places. But there’s a part of my brain that just clicks in and takes over. And the whole time I’m doing that, I’m fixing sentences. I think the problem is you get to a point as a writer where you’re on autopilot with all that stuff. I don’t have a checklist, but I’ve been doing it for so long I don’t even notice it when it’s happening.