Last summer, I found myself at a typical family barbecue. I was bored, bloated, and a look at my watch confirmed it: there was another hour until dessert. A disc jockey friend of mine had accompanied me that day, and we agreed a cultural crash-course might be more satisfying than a fourth round of ribs. I sent my DJ pal toward my parents’ record player. A few moments later, the opera playing out of their living room evolved into a new kind of Hip Hop—“Hip-Hopera,” if you will—and my parents’ assumption that record players simply played records changed forever. The piece of equipment had been theirs for decades—its secret life was troubling, but also exhilarating. If a record player could do this, what was the microwave capable of? The toaster?

Last summer, I found myself at a typical family barbecue. I was bored, bloated, and a look at my watch confirmed it: there was another hour until dessert. A disc jockey friend of mine had accompanied me that day, and we agreed a cultural crash-course might be more satisfying than a fourth round of ribs. I sent my DJ pal toward my parents’ record player. A few moments later, the opera playing out of their living room evolved into a new kind of Hip Hop—“Hip-Hopera,” if you will—and my parents’ assumption that record players simply played records changed forever. The piece of equipment had been theirs for decades—its secret life was troubling, but also exhilarating. If a record player could do this, what was the microwave capable of? The toaster?

I share this story because the keyboard we writers know so intimately is no less different or shocking. Like my parents’ record player, it lives a double life, spellbound in passionate affairs with a video game community that dotes on it as affectionately as we authors ever have. For every keystroke a writer uses to describe character or establish scene, somewhere in cyberspace a gamer uses these same keys to navigate gunships and commandeer submarines. Hone your fast-twitch muscles, and that slender spacebar can control more than just space—a boxer’s jab, a racer’s gear-shift, a sniper’s scope.

My parents learned that day that record players exist in a parallel universe; what they thought was simply a musical utility—a tool—audiophiles and DJs have turned into a device by which musical art can be both created and consumed. Similarly, there are some 34 million PC gamers1 who might say we writers haven’t a clue what the keyboard is capable of delivering. For them, the keyboard grants far more than access to entertainment. In this brave new virtual world, gamers have discovered—and are creating with each keystroke—an entirely new art form.

LEVEL ONE: INSTALLATION

The history of video games is told in generations. A big, weighty word for a thirty-year old industry, but fitting nonetheless—this is, after all, a marketplace that refreshes cyclically by purging its own technologies. Wholly and wholeheartedly, manufacturers abandon their video game console “families” for newer, shinier ones. Today, after three decades of hitting the Reboot button, the industry finds itself amidst a seventh generation that is doing just so. This seventh go is the period fanboys and journalists refer to as the Next Generation, the forward-looking term first coined in 2005 when Microsoft’s Xbox 360 console released. “Next-Gen” encapsulated the industry’s optimism for innovation—we were gunning it, leaving “Current-Generation” tech behind, a dusty box for little brother.

I joined Activision Blizzard on the heels of this hype, and spent the next three years as a Brand Manager as the company grew to become the largest and most profitable third-party publisher in the world. Like my former employer, the industry has refused to break stride. Since it began, Next-Gen has netted out prodigious advancements in graphical fidelity (the stuff that looks cool) and playability (the cool stuff you can control), but what makes Next-Gen worth writing about, and what makes Next-Next Gen worth dreaming about, is the recent leap forward in artistic achievement and experimentation.

I joined Activision Blizzard on the heels of this hype, and spent the next three years as a Brand Manager as the company grew to become the largest and most profitable third-party publisher in the world. Like my former employer, the industry has refused to break stride. Since it began, Next-Gen has netted out prodigious advancements in graphical fidelity (the stuff that looks cool) and playability (the cool stuff you can control), but what makes Next-Gen worth writing about, and what makes Next-Next Gen worth dreaming about, is the recent leap forward in artistic achievement and experimentation.

For some time I felt alone in this view, one of few standing firmly in both camps—writer and gamer, fiction-fiend and pixel-popper—but Next-Gen has, with its leaps in technology and massive install-base, brought the water to the masses. You no longer need three years in Activision’s trenches to spot the trend: games have developed depth, and the future of gaming will look a lot more like literature than flight simulators. This is, in many ways, the rise of a new novel. Like its lexicographic predecessor, the pixilated form revels in moral ambiguity, character motivations, conflicts between free will and fate. Take, for example, Activision’s recent record-breaking release of the game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. In Seth Schier’s review for the New York Times— yep, a game review in the Times—he called the title “unflinching yet empathetic.” Describing the series, Schiesel writes:

With its shift to the Modern Warfare line two years ago Infinity Ward clearly wanted to deliver a present-day shooter experience that not only trotted out the latest, greatest technologies for killing efficiently, but that also prompted the player to consider the emotional and psychological consequences. In the first Modern Warfare that was demonstrated most clearly in a now-famous sequence in which the player, acting as the gunner on an airship high above a battleground, obliterated the ghostly infrared images of people displayed on a screen with detachment and precision. It was a subtly powerful moment, with a game imitating life imitating games.2

Reviews like Schiesel’s hint at what is evolving under the hood—a new generation of games as mature and complex as any art form available to audiences today. And such games capture the depth and scope of the human condition through the power of collaboration, rather than singular artistic vision. Even the term for the gaming audience—“install base”—reinforces the integration of participant and medium. For these individuals are not merely “connected to” or “invested in” their form: they are installed.

LEVEL TWO: THE NEW BAKERY

The renaissance and risk-taking that Next-Gen represents could just as easily describe gaming’s evolving audience as it does its technologies and stories. This is a worldwide install-base tiptoeing toward a future of “game imitating life imitating games.”2 And as this tip-toe toward sophistication swells into a march millions-of-gamers deep, devotees to the book and letter can appreciate what directs its path: games and the players who love them aren’t locusts devouring time and attention from other art forms; rather, they are honeybees finding the nectar in narrative and then pollinating the desire for more of it, no matter the medium.

The only thing more exciting than the purity in this relentless hunt is the sheer number of hunters involved—the gaming audience is massive and still growing. Those spellbound keyboard-wielding PC gamers mentioned earlier compose the smallest slice of the gaming pie. Add console and handheld gamers and the medium comes to entertain 100 million people in America alone.1 The video game industry already beats Hollywood in revenue annually. Gaming hasn’t carved a piece out of the entertainment pie—it’s built a whole new bakery.

As a writer, I was excited to learn the empire wasn’t built on a secret recipe so much as some very familiar ingredients. There are protagonists and antagonists, epilogues and prologues, first-person and third-person. But it’s the sum of these parts—the finished good—that gamers hold dear above all else, and which fans of literature can identify with most. Gamers, like readers, covet immersion. It is the Holy Grail. Gamers want something they can sit down and lose time in, consuming level after level until their eyes can take no more and the urge to know what happens next gives reluctant way to body clocks that have timed out.

But this is no longer an issue of curfew, of child’s play. According to the Electronic Software Association3, the average gamer is thirty-five years old and has on average played games for twelve years. These men and women (females compose forty percent of all gamers) outspend every other form of entertainment, not because they are drawn to great games but because they stay drawn by their complexity and artistry.

So, yes, at their core, games are stories, consumed with great fanfare but also built with the same tools and materials we authors stash in our own toolboxes. That said, a game’s construction is highly specialized. Though expenses vary, your average novel costs time and energy, a laptop, and equal parts espresso and sanity. A video game needs these things too, but to the tune of around twenty-five million dollars in technical support. Nevertheless, here is the most important distinction: a game, though at one point written, is not created by a writer. Games are brought to life by developers. In my three years in the industry, the term never ceased to give me pause, given the extended family developers share in the wide world of storytellers. Whereas authors, journalists, screenwriters and playwrights can hypothetically create a finished product on their own, at their own pace, developers must “develop” their games gradually, usually over a two-year cycle of incremental gains. Games evolve from ideas into prototypes into weekly game “builds,” each week’s build increasingly fleshed out from an art, sound, and design standpoint. In linear games, each game “level” contains an environment, plot points, and like the chapters of a novel, these levels come together to form a larger narrative.

In most cases, the team that creates all this ranges from twenty to 200 dedicated individuals. The art department conceptualizes the game’s style, characters, and environments. Designers take those building blocks and create a set of features that will govern the game’s mechanics—what will the action look like and how will it stay interesting for ten to twenty hours? Sound engineers construct effects and music scores to complete the experience. Producers are the glue, making sure everything happens in-sync, on-budget and on-time. Amongst all of this: one writer.

He is a lot of things, our cousin. He is on his own, for one. Few writers have entered this space. He is both an explorer, stewarding the march of Next-Gen down a worthy path, and a pilgrim, setting up camp for the rest of us. He is also a prospector, a new-millennium 49er. As viewed against the full scope of the storytelling pantheon, gaming is an infant—the industry is new money, less than a half-a-century old. It boasts an unscarred landscape, veins of rich ore lying undiscovered just below the surface. The opportunity may be best put by Guillermo Del Toro, director of Oscar-winner Pan’s Labrynth, who told Wired magazine:

“We are used to thinking of stories in a linear way—act one, act two, act three. We’re still on the Aristotelian model. What the digital approach allows you to do is take a tangential and nonlinear model and use it to expand the world. For example: If you’re following Leo Bloom from Ulysses on a certain day and he crosses a street, you can abandon him and follow someone else…We could be doing so much more…In the next 10 years, there will be an earthshaking Citizen Kane of games.4

Forget the riches of revenue for a moment; right now, as you read this, gaming is rich in something far more valuable to us writers: gaming is rich with storytelling possibility. For all my insider knowledge of what the medium has done, and Del Toro’s optimism at what it might do, the idea that games might not have done it yet means that we, as storytellers, have reason to be a smidge jealous of our “developer” brethren and their install base. Their art is still maturing. Someone will soon make history. Gaming will evolve.

Independent game developers—stewards of the new and different, and usually on the cheap—are more aware of this than anyone. One of these developers, Jason Rohrer, creator of Passage, is credited by some as creating the first tear-jerker video game. In a recent New York Times Magazine article by Joshuah Bearman, he discusses the way in which video games will inevitably have to escape the influence of film to distinguish themselves, just as film had to do the same with its predecessor, the stage. “Eventually film figured out editing, camera movement—the tools that made movies movies,” he says. “Video games need to discover what’s special and different about their own medium to break out of their cultural ghetto.”5

Given the process and team dynamic described above, the question, then, is how does writing fit into the game industry’s creative process, and how will that relationship evolve as game development and the medium itself matures? Why should we care about the gaming recipe or, for that matter, whether or not it breaks out of its “cultural ghetto”? After all, if it does, what kind of art form will have escaped?

LEVEL THREE: SWEAT AND TREMBLE

Fair questions, for if members of the development team are drawing the game up, making it work, giving it sound, and constructing it from scratch, then what in the world does the writer really do? A game concept must be nurtured from something fun into something immersive, but how this is achieved through narrative is the writer’s responsibility. Though you may not pick up and play a game and immediately see the writer’s contribution, if you keep playing it, if you experience it beginning to end, those realizations become paramount. There is a script. A plot. Characters have dialogue. For gamers, winning the game is a formality, an expectation; beyond stepping into the boots of their favorite characters and watching these protagonists grow and evolve, they want to become experts on each character’s biography and relationships, each distant planet’s geography, the effects and counter effects of countless spells, weapons and artifacts. They game to experience. To understand. To learn.

The writer is busiest before the project has a team, conceptualizing all these details and developments so that when the artists and designers sit down to create, they are working not off ideas but a cohesive game, a narrative. Depth, rather than polish. Gaming is the ultimate show-over-tell medium. But for it to matter, for a gamer to remember it years later, and want to play it again, what’s shown must be rooted in a story worth telling.

But that’s just it, isn’t it? How can show-over-tell, a literary term, apply to a medium that shows-and-tells-everything? The act of reading and gaming are so fundamentally different that whereas they both require writers, any developer who hopes to raise gaming out of its “cultural ghetto” must first be tapped not into what the gaming audience experiences, but how—they need to get how games affect gamers emotionally. Literature has evolved; though today we read for different reasons than ever before, certain truths hold eternal: we read to understand characters different than ourselves, to experience other lives, to grow and learn through stepping into others’ shoes. Gamers play for these same reasons, but they also want to control characters different from themselves—to not only experience and see other lives, but guide them. Perhaps this is why winning is a formality, a diploma to hang in the garage. Winning comes after gamers have sweated and trembled, paused the game to compose themselves. Screamed and thrashed. As an audience, they are immersed on another level altogether. This level increasingly requires two things: new kinds of storytelling and new storytellers to bring it forth.

At Activision, I worked on award-winning titles and the opposite—games meant solely to entertain and fill rainy afternoons. The latter is what Rohrer referred to as the “cultural ghetto”; as in any other form, money still drives decision making and more often than not, game publishers will pick simpler premises to develop. This is not merely because they have proven audiences; they’re also more affordable to build out. Think Tom Clancy, Danielle Steele, Clive Cussler, or any other writer whose work has become a franchise of predictability.

But the kind of game Rohrer dreams of exists. I’ve played and worked on both types of games, and as a writer, toiling in each tier taught me as much about what makes art as what makes entertainment. For an outsider trying to understand the difference, the problem is that games, no matter their purpose or depth, can often look equally breathtaking. Even for hardcore gamers, graphics can be the most effective common denominator in judging a title’s ability to immerse; and to that end, games, and the characters and environments therein, have become uncommonly pretty. Female characters like Lara Croft are so beautifully rendered that they’ve become bona fide sex symbols—transcending off the small screen and onto the big. We’ve gone from 16-bit graphics to environments where blades of grass sway against the breeze. On the surface, these graphical advances might mean that to a non-scrutinizing gamer, most titles are looking good, or looking “cool.” What the graphical advances really mean is that under the hood, the processing power has gone up—developers can do more, experiment more, risk more. It means that a game writer’s narrative can be enhanced by craft—details, objects, expressions and atmospherics can all augment storytelling. Mood is now a factor.

But the kind of game Rohrer dreams of exists. I’ve played and worked on both types of games, and as a writer, toiling in each tier taught me as much about what makes art as what makes entertainment. For an outsider trying to understand the difference, the problem is that games, no matter their purpose or depth, can often look equally breathtaking. Even for hardcore gamers, graphics can be the most effective common denominator in judging a title’s ability to immerse; and to that end, games, and the characters and environments therein, have become uncommonly pretty. Female characters like Lara Croft are so beautifully rendered that they’ve become bona fide sex symbols—transcending off the small screen and onto the big. We’ve gone from 16-bit graphics to environments where blades of grass sway against the breeze. On the surface, these graphical advances might mean that to a non-scrutinizing gamer, most titles are looking good, or looking “cool.” What the graphical advances really mean is that under the hood, the processing power has gone up—developers can do more, experiment more, risk more. It means that a game writer’s narrative can be enhanced by craft—details, objects, expressions and atmospherics can all augment storytelling. Mood is now a factor.

Distill this further and the opportunity for artistic achievement in the games space becomes that much more exciting. True, like its brother-in-law the beach-ready paperback, there will always be mindless video games; scoring touchdowns and zapping aliens provide the same cracker-barrel escapism as pulp detective novels and bodice-rippers. But if we observe the last few years’ most popular games, they illustrate a clear shift in consumer palate toward more complex narrative. And it’s this small batch of sophisticated stories that have evolved what used to be called a good game into Great Gaming, a difference in quality akin to the disparity between good reads and Great Literature. Today they might compose a narrow bandwidth amidst the hundreds available to consumers, but these are the games tasked with evolving, growing big and strong into Citizen Kanes that might one day provide gaming with a permanent path out from its casual and iterative “ghetto.” And as game consoles become more technically powerful and developers more savvy, impressive graphics and gameplay will continue to shed their role as competitive advantages, and instead storytelling will emerge as the critical instrument teams will use to differentiate their art. Narrative and art are becoming less a bright possibility for gaming’s future and more likely the only path to the top of its mountain.

Of course, the ascent never really seemed necessary until recently. Game stories have historically been raw, a means to an end, form-fitted to help players understand and uncover game features and content. Players didn’t care if Pac-Man had daddy issues—they wanted to gobble ghosts. Things have changed. Video game writing is now recognized and awarded by the Writers Guild of America. 2009’s five nominees come from five different genres, ranging from casual to action to role-playing. The establishment of the award and its broad view is in ways a reflection of the depth game-writing now encompasses. The ‘gobbling ghost’ has become a ghost itself. Though every game writer contributes to the game’s design document, dialogue and story, the exceptional ones are working hand in hand to see what else they can do to build unprecedented immersion. These are the artists, creating games that are art. They suspend disbelief with their storytelling. Juxtapose vivid new worlds against meticulously researched historical fact. They are increasingly intimate, driven by characters that compel. They probe morality relentlessly. Like any great work of art, they challenge their audience, destabilize it, and demand collaboration.

LEVEL FOUR: AVOID THE RAILS

In Pac-Man, our hero’s quest is simple: clear the screen while avoiding certain ghosts and gobbling others. By today’s development standards, it’s an archaic design. Whereas an author might give her character a fork in the road and pick one for the reader, game writers now work in concert with designers to challenge gamers by giving characters countless forks. In short, complete rein over a character’s destiny. So that in this new future, Pac-Man can jump off your screen, gobble any ghost he wants, maybe even stop for a beer and some Thai before outsourcing his contract to another Pac-Assassin.

Today’s gamers demand depth through choice, and today’s great games challenge their audience not only through the minutiae of mini-quests but with mini-bouts of moral plight. Clint Hocking, a Creative Director at Ubisoft, the world’s fourth largest game company, refers to the successful experimentation in the “indie” development circuit as games that “have used what is innate to games—their interactivity—to make a statement about the human condition.”5

Though in no way a perfect example, I personally worked on one title that attempted to extract this effect through a popular proxy: your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man. Spider-Man: Web of Shadows was built so that the player would not only have the tools to defeat enemies, but to mold temperament. Righteous or antihero, staying a “friendly” neighborhood Spider-Man was solely the player’s choice. We did this because the novelty of simply swinging around town as Spider-Man had worn off. Immersion had to evolve beyond wearing the costume. So with every intention of challenging our audience, we redefined Spider-Man as ambiguous, left it up to the gamer to return verdict on Spidey—in turn, returning verdict on the gamer himself. A variety of reasons kept us from only scratching the surface, as in true “open world” games, choices have consequences beyond whether a city cheers or fears a Red or Black-Suited Spider-Man, or who in turn becomes Spidey’s ally or villain.

Character creation and development arguably hits its apex in the franchise Fable, where the entire game is based on the decisions a player makes, as the character will evolve into whatever he or she desires. The appeal lies in the immersion this provides—this is self-invention fused with complex consequences. Imagine a Choose Your Own Adventure book where in addition to affecting the character’s path, your choices affect the book’s page color, the book’s fonts, the book-jacket’s imagery. Complete control comes when every decision matters, when destiny is rewritten with each one. For games like these, an ambitious writer can spend weeks and months brainstorming “quests” and paths for his audience. The payoff? A gamer can spend years replaying them, experimenting with different causal relationships, observing change, learning. The idea that game stories may be less profound than short stories because they boast more outcomes is beside the point—this is a new art form, and just as film and television learned to inspire their audiences, video game writers are learning their medium is one that can embrace its replayability to reinvent how gaming narrative can challenge its audience.

But what about games that challenge more than their audience? A great work of art can destabilize far more than its following—it can infect the periphery. Whether destabilizing our senses of right and wrong or simply what’s proper, the capability of games to shake things up by literally providing the audience with the shaker makes it one of the most powerful art forms in history. When an art form is banned over violated codes of “…excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence, and anything dealing with the occult,”6 we need to ask ourselves if this censorship is truly protecting our citizens, or whether we simply haven’t recognized the artistry in the work. Yes, many games cash in on the liquid gold of blood, the silver of silicon’ed heroines, but can we honestly say that today’s morally-challenging video games do little more than erode our morals? What if, instead, some are breaking down boundaries of thought and expression? Just by sitting on the receiving end of politicians’ ire and parental fear, video games are joining a fraternity, walking a well-worn path: after all, the violated codes listed above refer not to a particular game, but were cited by a Canadian library in 1982 as grounds for banning The Catcher in the Rye.7

But what about games that challenge more than their audience? A great work of art can destabilize far more than its following—it can infect the periphery. Whether destabilizing our senses of right and wrong or simply what’s proper, the capability of games to shake things up by literally providing the audience with the shaker makes it one of the most powerful art forms in history. When an art form is banned over violated codes of “…excess vulgar language, sexual scenes, things concerning moral issues, excessive violence, and anything dealing with the occult,”6 we need to ask ourselves if this censorship is truly protecting our citizens, or whether we simply haven’t recognized the artistry in the work. Yes, many games cash in on the liquid gold of blood, the silver of silicon’ed heroines, but can we honestly say that today’s morally-challenging video games do little more than erode our morals? What if, instead, some are breaking down boundaries of thought and expression? Just by sitting on the receiving end of politicians’ ire and parental fear, video games are joining a fraternity, walking a well-worn path: after all, the violated codes listed above refer not to a particular game, but were cited by a Canadian library in 1982 as grounds for banning The Catcher in the Rye.7

I’ve seen the value of destabilization first-hand, watching as the developers of Call of Duty invested in it devotedly, dividends returning the favor promptly, elevating their property from risk-taker to headline-stealer to chart-topper. Call of Duty is by classification a first-person shooter, a typically linear experience that creates immersion through action intensity and tactical combat decisions. Publishers can differentiate their shooters with different weapons, time periods and villains, but some of the best games in recent history have leaned on writing to differentiate with risky and unique narrative devices. While at Activision I had the great fortune of working on Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, a title that inspired contempt for its fictional villains by placing the player into the shoes of a kidnapped politician in the very first scene of the game. Though the player can control the camera, he can control little else, forced to watch as he is driven through a war-ravaged Middle Eastern city to the center of a town hall where camcorder and wooden post await. The player watches as he is stood up, strung in, and executed—out of commission before he can affect a single thing. Later in the game, players crash-land after a nuclear bomb goes off. Although able to walk, there is no escaping the radiation that blankets a devastated playground the player finds himself in. There is nothing he can do—he falls to the ground and dies in what was one of the most overpowering moments in any game to date. Call of Duty was the first commercially successful shooter to kill off the protagonist, and though the game is unprecedented on all levels—gameplay, polish, sound design—it was this kind of risk that endeared the title to its audience. They were neither coddled nor shoved from level to level. Rather, they were immersed, invested, and thus affected. It was this level of artistic ambition that took Call of Duty from wildly popular with gamers to wildly popular period, the best selling shooter of all time.

Then came the sequel, and Call of Duty grew from a best-selling shooter to the best-selling form of entertainment of all time, earning $310 million on its first-day in stores in North America and the United Kingdom alone.8 It has gone on to shatter every record. The success can be attributed to a perfect storm of sorts, but one undeniable component was the storm of controversy Modern Warfare 2 brewed by extending the moral boundaries it drew in the first game to an entirely new order of magnitude for the sequel. Now came the slaughter of civilians. Though the gamer is allowed to skip a scene prefaced as potentially offensive, if he continues, it is wholly up to him to follow orders that demand he murders an airport full of innocent civilians. The narrative warns the gamer that accepting the mission will “cost a piece of yourself,” and the explosion of news and headlines following Modern Warfare 2’s release clearly indicate that it broke not just sales records, but social and societal boundaries. Whether one finds the game’s airport mission reprehensible or not, the ethical dilemmas it embraced represent a massive step-forward for gaming. Through narratives that “cost” gamers pieces of themselves, titles like Modern Warfare 2 have begun destabilizing not only their audience but every audience, using moral complexities in ways this new art form will only echo and grow upon.

In the aforementioned level, gamers were given a variety of options: they could cry foul and return the game in a huff; they could skip the level in question altogether; they could continue conservatively, allowing computer-controlled members of the team to shoot civilians instead; or they could lock and load, mow down every digital innocent. No matter their selection, the five million individuals who bought Modern Warfare 2 on its opening day were engaged in a way that makes video games so uniquely powerful as an art form: they were given a choice in the first place.

The collaboration between game and gamer is intrinsic to what a game is, who a gamer can be—without a gamer’s input, the game’s narrative will stall and fail. Some might say that the entire point of literature is for a reader to experience an individual point of view, a unique and singular vision of the world. But certainly the best novels and stories make demands on its readership. In fact, readers have plenty to do. They must piece language with pieces of themselves; they must imagine and make connections; they must think forward and back. In his ode to craft, On Writing, Stephen King whittled down an author’s main job to three categories: narration, description, and dialogue.9 From there, it is dependent upon the reader to weave our words with their imagination, to work, build, and create life. The greatest novels I’ve read are the ones that demanded the most from me—as the stories became more fully mine, they became richer, more meaningful. Similarly, the worst novels I’ve read have demanded the least—these were the slideshows, pages of prose sliding past my eyes but never penetrating their glassy gaze.

The collaboration between game and gamer is intrinsic to what a game is, who a gamer can be—without a gamer’s input, the game’s narrative will stall and fail. Some might say that the entire point of literature is for a reader to experience an individual point of view, a unique and singular vision of the world. But certainly the best novels and stories make demands on its readership. In fact, readers have plenty to do. They must piece language with pieces of themselves; they must imagine and make connections; they must think forward and back. In his ode to craft, On Writing, Stephen King whittled down an author’s main job to three categories: narration, description, and dialogue.9 From there, it is dependent upon the reader to weave our words with their imagination, to work, build, and create life. The greatest novels I’ve read are the ones that demanded the most from me—as the stories became more fully mine, they became richer, more meaningful. Similarly, the worst novels I’ve read have demanded the least—these were the slideshows, pages of prose sliding past my eyes but never penetrating their glassy gaze.

The collaboration that games demand follows suit. The worst-reviewed games are often “on rails,” a game-critic’s term for linearity which is a nice way of saying the title was too simple, demanded too little, and was therefore a bore. On the other hand, the best-reviewed games demand investment from their audience; unlike collaboration between reader and author, gamers are not imagining settings and time periods so much as exploring them. Yet both these actions require deciding what details matter and what don’t, acting on those decisions and then living with those consequences.

And herein lies collaboration’s pay-off: gamers and readers feel their stories more profoundly, the art resonates, rings true. Of course, the roads to emotional pay-off in reading and gaming are one-way streets heading in different directions, something developers are aware of and increasingly experimenting with. Whereas in words we feel with protagonists as the action unfolds, in games we feel by unfolding the action ourselves, unfurling the carpet and then walking it.

BioShock, 2007’s Video Game Awards’ Game of the Year, placed the gamer in an underworld utopia ravaged by its own citizens, individuals who in their attempts to perfect life with genetic enhancement poisoned themselves and their world. In the game, players come upon a choice: heal a possessed little girl or harvest her. Though she may assist you later, you need her power to survive now. Throughout the adventure, gamers picked life or death for countless individuals in a narrative device that stretched the moral fibers of what most players had come to expect from their games. Taking it further, the developers programmed “Achievements” for gamers who stayed true to their code of ethics—rewards lay in wait for those who remained consistent to their heal versus harvest policies. BioShock was revered because it gave gamers free will. Bioshock will be remembered because that free will came with a price. To keep the story moving along, gamers had to collaborate, make decisions and live with them; but while decision-making was nothing new, the accompanying emotional ramifications certainly were. The pride, the shame. The realization that one felt neither. As games continue to challenge, it is their inherent ability to collaborate that will make them increasingly complex. A gamer’s “work” is a cornerstone to what makes his game art—it is the promise of enrichment in return for engagement, a way to break “off the rails” and take himself to places he has never been.

LEVEL FIVE: INDEBTEDNESS, CONNECTEDNESS

If you still can’t see the artistry inherent in video games; if you don’t see the magic in a record player the way my parents did, all I ask is this: hang on. The game industry will adapt. In order to satisfy the fractured and particular tastes of its audience, publishers are creating new genres, game types, and brand extensions with dizzying disregard for how many games players can actually afford to buy. Your local GameStop retailer may still organize its shelves by platform—Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, Wii—but one day soon it may be forced to drill down not just by audience—All Ages, Teen, Mature—or game type—Action, Shooter, Strategy—but also story type: Sci-Fi, Horror, Mystery, History, Sport. With a compartmentalized marketplace, fans will flock to the stories they love most. They already seek out their favorite developers; who is to say they won’t begin looking within them, for their favorite writers?

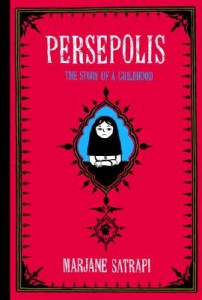

It could also be the other way around. Just as Steven Spielberg has begun producing games, maybe an established novelist will adopt this new creative domain as well, helping migrate a readership by offering his or her next narrative in the form of a game. Guillermo can’t do it alone; the Citizen Kane of games may well come from one of you, or your students. But it is coming. After all, until quite recently, many people thought the only place graphic novels belonged were in the basements and bedrooms of teenage boys—the same environment most critics have relegated video games, coincidentally. Yet with the emergence of work like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, to name just two, graphic novels have found a place on the shelf with literature. And even a Pulitzer nod, in the case of Spiegelman.

It could also be the other way around. Just as Steven Spielberg has begun producing games, maybe an established novelist will adopt this new creative domain as well, helping migrate a readership by offering his or her next narrative in the form of a game. Guillermo can’t do it alone; the Citizen Kane of games may well come from one of you, or your students. But it is coming. After all, until quite recently, many people thought the only place graphic novels belonged were in the basements and bedrooms of teenage boys—the same environment most critics have relegated video games, coincidentally. Yet with the emergence of work like Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, to name just two, graphic novels have found a place on the shelf with literature. And even a Pulitzer nod, in the case of Spiegelman.

The narrative devices in Fable, Call of Duty, and BioShock introduce far more than perspective and pace into a story—they inject emotion. And whereas the game designers and art department and sound engineers take away a writer’s need to describe and establish scene, they cannot create the most important differentiating factor outside of fresh content and innovative gameplay: storytelling with consequences. Immersion that resonates and moves a player the way great literature resonates and moves a reader. As a form, writers interested in video games can be empowered in ways their peers have never known. If they can operate within timelines and technical limitations, if they can share the process with a large cross-functional team of equally dedicated individuals, they will be at the forefront of an entirely new storytelling medium—the first art form to empower its audience through direct action and consequence.

In her 2007 Harper’s essay “Literary Entrails,” Cynthia Ozick distilled a letter of James Wood’s to get to the core of why Gustave Flaubert might have fathered the modern novel. For Ozick and Wood, Flaubert’s rank at the top has less to do with his personally evolving literature than how generation to generation of the written word reflects the evolution he set forth. For Ozick, “The key is indebtedness. The key is connectedness.”10

Video games are as indebted and connected to literature as television and film once were. The pixel and the page are linked, now and forever, and as gaming continues to build a stage to one day stand tall upon, we, as fiction writers, would be wise to stand in solidarity with our fellow artists. If the key is indebtedness, connectedness, we may soon see literature tap into the video game install-base, as indebted and connected to gaming as games are today. Because video game popularity is transitive. It is popularity in story and narrative, something challenging, destabilizing and collaborative. Because it is popularity in art. This new frontier in creativity may come to mean new audiences for every form, hordes of fiction-fiends and pixel-poppers seeking what one camp provides and the other cannot, what both provide without fail. Games aren’t toys, but we would be wise to play them. The hope for Great American Art can be sourced to the hunger of a Great American Audience.

For both camps, millions await.

Extras

- Interested in what video games’ 8th generation will look like? Watch this video on Project Natal for a glimpse at what the “Next-Next Gen” mentioned earlier might provide us.

- Though not discussed here, video games’ portability is a major reason for their relevance. Today’s Game Boy descendents – the Nintendo DS and Sony PSP – accompany their owners everywhere, and play movies, music and even surf the web. But what happens when they start competing with the Kindle?

- Hard to say so early on, but a new game called Heavy Rain is doing its best Citizen Kane impression. With the developer’s CEO calling his game a “journey,” and claiming gamers will experience its story “in a physical sense, changing it, twisting it, discovering it, making it unique, making it yours…” we should probably check back in on its success in the marketplace and with audiences. Learn more here.

- Still hungry? Eat your heart out with an aggregate of top gaming news at this site.

EDITOR’S NOTE: As this article was being published, the Writer’s Guild of America announced its 2009 nominations for best video game writing. As discussed above, the “destabilizing” narrative behind Modern Warfare 2 was officially recognized by the WGA for its outstanding storytelling, earning one of the five nominee nods. The final game the author worked on at Activision, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, also received a nomination.

Sources

1: Interpret’s New Media Measure. 4th Quarter 2008.

2. “Choices in Infiltrating a Terrorist Cell” by Seth Schiesel, New York Times, November 1, 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/12/arts/television/12call.html>

3: ESA <http://www.theesa.com/facts/index.asp>

4: “Q&A: Hobbit Director Guillermo del Toro on the Future of Film” by Scott Brown, Wired, May 22, 2009 <http://www.wired.com/entertainment/hollywood/magazine/17-06/mf_deltoro?currentPage=1 >

5: “Can D.I.Y. Supplant the First-Person Shooter?” by Joshuah Bearman, New York Times Magazine, November 13, 2009 <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/15/magazine/15videogames-t.html>

6: “Banned Books” by M.J. Stephey, Time, September 29, 2008

<http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1842832_1842838_1845068,00.html>

7: “Banned and/or Challenged Books from the Radcliffe Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century” by American Library Association <http://www.ala.org/ala/issuesadvocacy/banned/frequentlychallenged/challengedclassics/reasonsbanned/index.cfm>

8: “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 destroys records in first day sales rampage, pulls in $310M” by Robert Johnson, NYDailyNews.com, November 13, 2009 <http://www.nydailynews.com/money/2009/11/13/2009-11-13_video_game_blitz.html>

9: On Writing by Stephen King, Pocket Books, 2000

10: “Literary entrails: The boys in the alley, the disappearing readers, and the novel’s ghostly twin” by Cynthia Ozick, Harper’s, April 2007 <http://www.harpers.org/archive/2007/04/0081479>