If you do a search on YouTube for The Rolling Stones, you can find footage from hundreds of their shows, a good dozen or two from before 1969. You can still watch Brian Jones tapping a xylophone on “Under My Thumb,” strumming a sitar on “Paint It Black,” banging on a piano’s keys during “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” Jones was only 27 when he died under mysterious circumstances, and the shots of him from these performances are haunting: blacked-out eyes, impish grins, vacant stares. He bobs and strums without emotion, without expression. Jones looked like a specter even while he was alive.

If you do a search on YouTube for The Rolling Stones, you can find footage from hundreds of their shows, a good dozen or two from before 1969. You can still watch Brian Jones tapping a xylophone on “Under My Thumb,” strumming a sitar on “Paint It Black,” banging on a piano’s keys during “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” Jones was only 27 when he died under mysterious circumstances, and the shots of him from these performances are haunting: blacked-out eyes, impish grins, vacant stares. He bobs and strums without emotion, without expression. Jones looked like a specter even while he was alive.

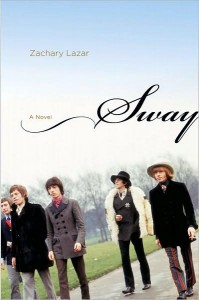

Zachary Lazar bottles those feelings of mystery and darkness in his second novel, Sway (January 2008 / Little, Brown). The book opens with three consecutive scenes, each occurring just prior to events most readers will be familiar with: Bobby Beausoleil in the minutes before the murder of Gary Hinman; the Rolling Stones on their first tour, getting a taste for celebrity; Kenneth Anger during his childhood and adolescence, as he takes ownership over his sexuality and begins a lifelong relationship with the occult.

Sway follows all three storylines through the end of the decade: the Stones’ rise to cross-Atlantic stardom, Anger’s itinerancy and sporadic cinematic successes, Beausoleil’s California-style desperation and his corruption at the hands of Manson. The plots culminate in the making of Anger’s film Invocation of my Demon Brother, in which Beausoleil acts and for which Jagger provides the soundtrack. Lazar uses the film to tie three stories together–and to focus on the often-ignored darkness of the era, the shadow lurking just on the other side of Woodstock.

Except in the sections on Anger, Lazar sticks almost exclusively to first names—Bobby, Charlie, Mick, Keith, Brian—evoking a strange, disconnected feeling that captures the fame- and drug-addled states of its protagonists and the paranoia of the period. The Anger sections are quieter and more intimate, effectively communicating the particulars of his life and career—he is by far the least-known of Sway’s characters. Lazar paints Anger as a prophet, a contrast to the Manson Family and the Stones, who serve as avatars of the period’s thanatomania and nihilism.

There are, of course, huge dangers in taking on a project teeming with cultural icons whose stories we feel so familiar with: Manson’s satanic charisma, Jones’ exile and early death. In the hands of a lesser writer, the braided storylines of Sway might quickly turn into a familiar and tedious exercise in deprecatory nostalgia. There is little need to resurrect that 1969 Spirit of Love and Chaos again only to condemn its failure to live up to its self-limiting idealism—a practice whose continuing perpetration only serves to heighten our sense of that grooviest generation as mortally self-absorbed.

But Sway survives these menaces, largely due to Lazar’s emotional acuity and his ability to contextualize and humanize his characters; his in-depth descriptions of the Jagger/Richards music catalog and Anger’s films manage to feel compelling and fresh. Lazar also incorporates the larger world of visual art, drawing a particularly subtle and brilliant connection between the late 60s zeitgeist and specific pieces from the Northern European Renaissance. These allusions and descriptions accumulate into acute feelings of fatalism and doom. They highlight, in a pleasurable way, our awareness of Sway as a constructed object, one created from associations that exist as much today, in the mind of the backward-facing reader, as they did in 1969. Sway’s success rests as much on the raw elegance of its prose (and the intelligence of its author) as it does on the automatic, lurid interest we have for its characters. Even 60s cynics may find themselves moved by this novel’s ambition, its subtlety, its parade of tension- and grace-filled moments.

For Further Reading

Zachary Lazar’s first novel is Aaron Approximately (1998)