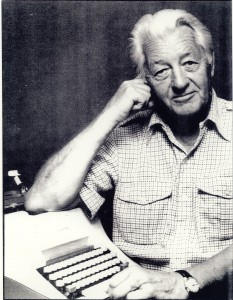

Wallace Stegner

As the fall semester began, I found myself wanting to flash this quote in front of my creative writing students. It comes from an acknowledged master teacher, after all—one most students haven’t read, but whose name resounds through the coveted Stegner Fellowships at Stanford—and it sounds appropriately daunting for the beginning of a class.

Don’t fool yourself, it suggests. You have lots of work to do. More than you can imagine.

This feels right to tell an aspiring writer, because the craft certainly involves more work than anyone imagines upon entering into it. But I didn’t use this quote because I couldn’t explain what or who this apprenticeship was to. Is it to the craft itself? To some ideal (and idealized) reader? To language, truth, beauty? Stegner didn’t elaborate on this subject as I wish he had, but the word “apprenticeship” itself typically refers to a specific aspect of the relationship between a teacher (usually a series of teachers) and a student. We more often use the terms mentor and protégé in this context, but apprentice reveals something different and instructive about the student/teacher dynamic that those terms do not.

Two types of apprenticeship immediately come to my mind. The first is the kind one takes on within a trade, such as plumbing. Being a plumber’s apprentice, according to Plumbersnetwork.net, requires “4 to 5 years of education, with 144 of those hours yearly being classroom education and the rest hands-on experience.” Apprentice plumbers learn the practical techniques of the trade, such as how to determine the age and condition of a pipe, how to interpret building codes, and how to read blueprints. With the requisite training and experience, they can become journeymen; with still more (plus an exam) they can become master plumbers.

Apprentice plumbers also need to learn the intangibles of their trade. They learn what it takes to call themselves plumbers (how to run a business, how to interact with clients). It’s the same with apprentice writers. They learn, from masters and journeymen alike, the tricks of the trade (establishing voices, pruning sprawly plots) and how to behave (bonhomie with rivals, geniality at readings). They learn what it takes to call themselves writers: lots of self-discipline, thick skins when it comes to rejection, etc.

For some, this is as far as the training goes. But at a certain point, the tradesman model of apprenticeship exhausts itself. Nascent writers who want their apprenticeships to be about more than practical technique and professional behavior are rewarded with a refreshing truth: apprenticeship is also about learning an approach to the task of writing and an approach to one’s emotional material.

This brings me to another kind of apprentice: those who serve sorcerers. Two hundred-some years ago Goethe cemented the archetype of the sorcerer’s apprentice in the poem “Der Zauberlehrling”, made popular by Walt Disney in the 1940 film Fantasia. In this story the apprentice, lazy and looking for short cuts, tries to get a broom to clean the master’s quarters for him and ends up causing a flood that only the master can stop. We see a version of this same cautionary tale unfolding in the stories of Faust, in Frankenstein, 2001, etc.: don’t mess with what you can’t truly control. Sorcerer’s apprentices get in over their heads and cause trouble by dealing, though not yet prepared, with the forces of the master, and the masters must bail them out.

Superficially, this kind of master/apprentice relationship is unlikely to unfold in the literary world. It’s hard to imagine disaster befalling anyone from trying to mimic the prose style of Jhumpa Lahiri or Dave Eggers, nor would it be necessary for those authors to swoop in and save the day. This is because mastery in literature is not about style. Master writers (literally, those who have written a masterpiece) are analogous in the first apprenticeship model to the master plumber, who must pass an exam to earn the title. They pass the “masterpiece test” because they’re capable of channeling the emotional forces of the self; they go into the self and/or the collective genius (see “Trust Your Genius, Even if it Doesn’t Belong to You”) and they come out with art.

This process is not technical but alchemical; it is fundamentally dangerous to the self because it exposes the self to peril, while mere technique and professionalism do not. The sorcerer can hardly be seen as an innocuous, benevolent character because he works with (to borrow the title of a Philip Pullman trilogy) His Dark Materials. The model for Goethe’s Faust was quite likely an alchemist.

Foremost among the “dark materials” at work in writing is what emerges from poking around in the depths of the self, a process that ushers in literature and is a byproduct of creating it. These materials—the memories, self-conceptions, and lies that slumber inside us and probably ought to be left alone—cannot be approached directly, but can only be made manifest by the creation of art. If I could tell this story the easy way, author after author has said, I would never have needed to write it. The process of making literature requires a certain amount of sorcery, or at the very least alchemy, because it involves transforming deeply personal, non-shareable emotional experience into completely shareable aesthetic experience. (For a more thorough discussion, see “Peering into the Character/Self Vortex,” Part I and Part II).

Foremost among the “dark materials” at work in writing is what emerges from poking around in the depths of the self, a process that ushers in literature and is a byproduct of creating it. These materials—the memories, self-conceptions, and lies that slumber inside us and probably ought to be left alone—cannot be approached directly, but can only be made manifest by the creation of art. If I could tell this story the easy way, author after author has said, I would never have needed to write it. The process of making literature requires a certain amount of sorcery, or at the very least alchemy, because it involves transforming deeply personal, non-shareable emotional experience into completely shareable aesthetic experience. (For a more thorough discussion, see “Peering into the Character/Self Vortex,” Part I and Part II).

If we extend the metaphor of the sorcerer’s apprentice model, the “danger” of writing involves improper use of that alchemical creative process—more specifically, entering into the alchemy without full respect for it, as Mickey Mouse does in Fantasia. We learn this respect from our mentors/masters. We figure out, from their example, how to deal with those dark materials in a constructive feedback loop we call creativity.

I’ve been lucky to have apprenticed myself to people who had respect for that alchemy. From filmmaker Ken Jacobs, I learned how important it was to let myself get lost in a work so that I might find its most natural contours. From Stan Brakhage, another filmmaker, I learned how to look at things in the world from the perspective of eternity. From novelist Robert Olen Butler, I learned how steadfast you have to be in order to earn the name of artist—like Odysseus tied to the mast. From novelist Steve Katz, I learned how the writing endeavor is a life-long one, and how a true voice always finds its form.

My writing resembles none of these mentors’ stylistically at all—two of them aren’t even writers—and that’s because I didn’t learn style from them. Style is nothing but window dressing. What we really learn from our masters is an approach to our materials and a respect for the creative process. That’s why we hang around with other artists. That’s why MFA programs exist. It’s an old, time-tested model; you sit at the feet of the teacher and learn how the teacher does things, makes things. The classical tai chi text “The Song of the Thirteen Postures” reads, in part:

To enter the door and be shown the way,

you must be orally taught.

Practice should be uninterrupted,

and technique is achieved by self study.

You must be orally taught because what you learn as an apprentice simultaneously transcends technique and resides beneath it. Technique is achieved by self study because by working diligently we find our best modes, our ways of using our tools to the fullest. We can learn from people we don’t resemble stylistically, and even those in entirely different art forms, because what we learn from our mentors is about the relationship between artists and their art. We learn to work with those materials of the self that we turn into art—using an alchemy we must ultimately devise on our own, learned though the examples of others who have devised alchemies on their own.

Plumbing, writing isn’t. Sorcery, writing isn’t. Maybe somewhere in-between.