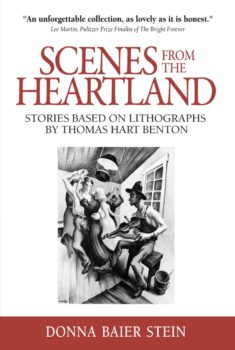

One day, considering what to write, I sat staring at an early edition print by Thomas Hart Benton hanging on my office wall. “Spring Tryout” (1943) shows two boys and a horse galloping across a field. Everything is in motion in the picture—the cantering horse, which the first boy can hardly control; the racing clouds; even the windswept trees in the background. Yet it is the second boy, who’s just fallen off the back of the horse, caught in the moment before he lands on the ground—the surprise evident on his face—that conveys the snapshot instant of the moment most clearly.

This rural setting and the scene the artist portrayed had no connection to my life, but I felt compelled by the narrative potential the scene evoked. I’d been writing short stories for years, some triggered by events in my personal history, and now I wanted to see beyond the limits of my own “story,” to transport my imagination to a time and place radically different than my own, and to escape the constraints of my life experiences. Benton’s lithograph seemed to offer that chance.

This rural setting and the scene the artist portrayed had no connection to my life, but I felt compelled by the narrative potential the scene evoked. I’d been writing short stories for years, some triggered by events in my personal history, and now I wanted to see beyond the limits of my own “story,” to transport my imagination to a time and place radically different than my own, and to escape the constraints of my life experiences. Benton’s lithograph seemed to offer that chance.

Benton was arguably the best Regionalist painter of the 20th century. He was the first American artist to appear on the cover of Time magazine, and his art illustrated the cover of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. Benton’s most ambitious work is “America Today,” now housed in a special room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I own a book called The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton (1969), compiled and edited by Creekmore Fath. The book reproduces eighty of his lithographs and includes, in most cases, the date and place each was first drawn.

On a recent trip to visit Benton’s museum in Kansas City, Missouri, I learned that during the summers, the artist often took long walking journeys. On these trips, he sketched the ordinary Americans he saw: coal miners, steelworkers, loggers, field hands, and farm wives. Benton said of his work, “Every detail of every picture is a thing I myself have seen and known. Every head is a real person drawn from life.”

Here was the dilemma: these boys were ostensibly real people, a real scene that had once likely taken place. In fact, I later learned Benton had drawn the picture from a memory he had of his own childhood. One of the boys pictured was Benton himself. Yet as a fiction writer, my desire was not to capture the truth of the actual image (the way a photographer might want to do), but to imagine a potential story behind this scene, to use these real, though usually unnamed, people in Benton’s lithographs merely as jumping off points. Here is what I wrote:

The boy rode a dark horse, crossing a field of yellow stargrass and olive green shadows. A slip of a stream, with logs nearby so recently cut their ends were white and circled with clear, brown rings. The horse’s ears pointed toward a gray farmhouse to the east, and to the left of that, low stalls and three spreading cherry trees blooming pink. On the side of the house a single window opened like an unseeing eye. (“Spring 1933”)

Writing those words started my practice of ekphrastic writing, writing based on a visual image. The etymological origin of “ekphrastic” comes from the combination of two ancient Greek words: ek, which means “for the sake of,” and phradzein, which means “to show, point out, or describe.” We could say the process of writing ekphrastic fiction or poetry is the process of verbalizing an inanimate, non-verbal object. That’s what I set out to do with that first lithograph, “Spring Tryout,” knowing that writing from a visual image could easily plant the seeds for a story’s plot line.

I have always had more doubts about my plotting skills than my language skills. So I stared at the boys, the horse, the cherry trees, and that small gray farmhouse. I put myself inside this scene, imagined the spring day, the boys’ carefree fun. Once inside the image, I knew other elements of that particular visual gestalt existed, some unseen—similar to the way we walk into a party and know that everyone we chat with has multiple story lines active in their lives. It may be either the blessing or the curse of the writer to understand this. What I found working from a visual image did for me as an author was to provide a framework from which I could expand. I knew because of the setting of this image that I would write a story involving this place (a Missouri farm) and time (spring in the early part of the 20th century). That helped provide parameters for the setting. Seeing freshly cut logs in the picture made me realize someone must have been close by recently, as well, someone older and bigger than the boys. Someone who lived in the farmhouse I could see in the distance? Who were the parents of these carefree boys? I saw the boys having fun—in the way that a wild horse you can barely control is thrilling to boys this age—but, as an adult, I knew someone had to have done the chores, taken care of the animals, laundered the boys’ clothes. One visual element necessitated the existence of other elements still unseen, leading me to the central character: their mother. It was those unseen elements that I as a writer had the privilege of uncovering. I wrote:

On the side of the house a single window opened like an unseeing eye. Behind it the boy’s mother dreamed. (“Spring 1933”)

To be candid, at the time I was experiencing some marital strife. As a writer, I tend to mine my feelings. Part of what draws me to literature—both as writer and reader—is a deep, abiding interest in what it means to be human. Writing about a character’s inner life helps clarify my own and vice versa. It’s symbiotic, really. The more I know about who I am inside, the more full-bodied I can make my characters. And the more I understand what makes my characters act as they do, the more I can grasp the full range of human potentials. So, as I created this mother of two young boys, a woman I named Amber, I naturally found myself integrating those marital problems into her life, weaving the anger and fear into her day-to-day experience as they were currently bound up with my own. In doing so, I was able to explore my own struggles in this transposed way, illuminating both real life and this fictional one. Yet because I understand the complexity of relationships, of all people, I never had a desire to make my protagonist guilt-free. I tried hard as I wrote the story to understand and explain what role she might have played in the troubles with her fictional husband, how her own actions and desires might have contributed to where they found themselves as a couple.

Over the next years, I selected eight more lithographs from the Fath book that resonated with me. All were set in Missouri and Arkansas in the 1930s and 1940s. And each of the stories I wrote after the first one mirrored its pattern of creation. One by one, I chose a picture that engaged me. Each time, I imagined lives for the people Benton had portrayed: a black fiddler sitting on a stool while a white couple and several women dance; a well-dressed man standing near the white carcass of a cow, suitcase dropped on the dirt road behind him, stroking his beard as he looks at a boarded-up shack; a man and a boy standing near an old gas station with a single pump, raising their arms as a train rolls past in the distance. Some incorporated elements directly from my own experiences, as I’d done with the character of Amber in that initial exploration. Others did not. But I found that despite the scene or setting or the individuals, there was always something about these lives that resonated with my own. How could they not when we share a common humanity, even though our cultural milieus are very different?

Over the next years, I selected eight more lithographs from the Fath book that resonated with me. All were set in Missouri and Arkansas in the 1930s and 1940s. And each of the stories I wrote after the first one mirrored its pattern of creation. One by one, I chose a picture that engaged me. Each time, I imagined lives for the people Benton had portrayed: a black fiddler sitting on a stool while a white couple and several women dance; a well-dressed man standing near the white carcass of a cow, suitcase dropped on the dirt road behind him, stroking his beard as he looks at a boarded-up shack; a man and a boy standing near an old gas station with a single pump, raising their arms as a train rolls past in the distance. Some incorporated elements directly from my own experiences, as I’d done with the character of Amber in that initial exploration. Others did not. But I found that despite the scene or setting or the individuals, there was always something about these lives that resonated with my own. How could they not when we share a common humanity, even though our cultural milieus are very different?

Yet despite the imaginative elements that I brought to scenes, and how they became points of departure for my own work, it was still important to me that the historical facts about the era portrayed in each lithograph be correct. I needed that for grounding, for authenticity. And so I examined the images in the lithographs as studiously as I’d tried to tease out what was happening beneath the surface or beyond the margins of what the pictures portrayed. For example, one image was of two women standing on the bank of a flooded river. I knew from the notes in the book that Benton had drawn this in 1937. Research led me to uncover that there was a Great Flood in January and February of that year, one that left one million people homeless. I meandered online through diaries of people who’d lived through the flood, Coast Guard reports, and newspaper accounts. I acquired far more research than was needed. The details fascinated me, and a few of those details (like President Roosevelt’s car being flooded on his second inauguration) found their way into the story. When I stumbled onto the description of a church that straddled the state line between Missouri and Kentucky, on a river landing actually called Compromise, I felt like I’d struck gold. I was already conscious of and worried by the increasing divisiveness in America. And here, in America’s past, was this perfect metaphor: a church where people refused to cross to the other side. What follows is my own writing, based on what I discovered through online research:

The New Madrid Baptist Church had been built on a half-acre clearing in the woods high on a hill inside the oxbow curve of the Mississippi River, on the state line at a landing called Compromise. New Madrid County, Missouri, sat on one side and Fulton County, Kentucky, on the other. Half the church’s thirty benches of hand-hewn sycamore were in one state and half in the other, enabling the members of the congregation to walk up the aisle on their side of the church and attend services without ever stepping into the other state. Come Sundays, folks would file in, lean their guns against the wall, and sit down in the pews on their designated side. Everyone would kneel for prayer except a man who stood guard at the end of each aisle in case any member from the opposite pews decided to start a fight. No one had caused any trouble for ages, but the guns were still kept at the ready. Families from the two counties had been feuding since the Civil War, when a flag officer from Fulton County turned traitor and helped a Union gunboat attack Island Number 10, leading to the Confederates’ first loss of a battle position on the Mississippi. (“A Landing Called Compromise”)

It was important the historical details in the stories were authentic because I wanted to honor both Benton’s artwork and the real-life people he had portrayed. Again, the visual images provided the framework of the story, the parameters. I had to know the price of cereal, what women used to clean their homes, who might exhibit at a county fair. Otherwise, the lives of the people whose stories I wrote would be less “true.” The emotional lives of the characters I created were and are imaginary. But the settings they inhabited were not.

Did I as a writer worry about using real people in my writing? Not as I was writing the stories—I couldn’t or the imaginative process wouldn’t take flight. In fact, it was somehow easier to write about these people from another generation than it was to fear friends and family of my own era might see themselves in what I’d crafted. The stories in my first collection, Sympathetic People, aren’t necessarily autobiographical, but each has its seed in something that happened in my own life or the life of a friend. As such, friends and family members appear in disguised ways. And yet despite the transfiguration that takes place between fact and fiction, it’s always a balancing act between the desire to tell the truth and to not betray others.

Did I as a writer worry about using real people in my writing? Not as I was writing the stories—I couldn’t or the imaginative process wouldn’t take flight. In fact, it was somehow easier to write about these people from another generation than it was to fear friends and family of my own era might see themselves in what I’d crafted. The stories in my first collection, Sympathetic People, aren’t necessarily autobiographical, but each has its seed in something that happened in my own life or the life of a friend. As such, friends and family members appear in disguised ways. And yet despite the transfiguration that takes place between fact and fiction, it’s always a balancing act between the desire to tell the truth and to not betray others.

For this project, then, I studied not my friends and family but people I saw in Benton’s lithographs. Still, I wondered about their lives, the same way I wonder about the lives of people I see at a party or on the street: What brought them here? What do they dream? What are their hopes and fears they’ve kept tucked away?

Turning to images for creative inspiration is a well-trod path, of course. Keats did it in “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Tracy Chevalier did it in Girl with a Pearl Earring, a novel based on a poster Chevalier owned of the original painting by Vermeer. And remember the painting on the wall of the Spouter Inn in Moby Dick? The large mural appears to Ishmael when he enters the inn as “chaos bewitched.” Ishmael’s attention is caught by “one portentous something in the picture’s midst. That once found out, and all the rest were plain.” After studying the painting, Ishmael imagines that it shows a vessel with a whale impaled on its mast-heads. Melville devotes a lot of attention to this painting and uses it to help introduce Ishmael’s state-of-mind and establish foreboding.

By imaginatively playing with a visual work of art, the writer can expand its meaning—not in terms of enlarging the original work, but in terms of offering more possibilities. By bringing two imaginations into conversation with one another—that of the visual artist and that of the writer—something new is born. Not something that supersedes the original, but something unique. And what perhaps surprised me most on this creative journey was that despite my initial desire to stop writing semi-autobiographical fiction, despite attempting to escape to times and places radically different than my own, I invariably found parts of my own psyche in the people portrayed in Benton’s lithographs.

By imaginatively playing with a visual work of art, the writer can expand its meaning—not in terms of enlarging the original work, but in terms of offering more possibilities. By bringing two imaginations into conversation with one another—that of the visual artist and that of the writer—something new is born. Not something that supersedes the original, but something unique. And what perhaps surprised me most on this creative journey was that despite my initial desire to stop writing semi-autobiographical fiction, despite attempting to escape to times and places radically different than my own, I invariably found parts of my own psyche in the people portrayed in Benton’s lithographs.

In short: I could not escape the limits of my ways of perception. I saw the world Benton had portrayed through my particular psychic lens. This is the way we invariably view the world, through the lens of our own memories and life experiences. As I wrote, I realized that the long-dead folks Benton had drawn had interior struggles not so different from my own. Marital and parental challenges, searches for spiritual meaning. Though Benton’s lithographs depict the past, I realized very quickly that the people he portrayed faced issues that are still front and center today: women’s rights, racial inequality, corruption. Their griefs, their grit, their great loves and losses were, in fact, similar to our own more than half a century later. Using Benton’s art as writing prompt gave me a window into the past, a way to see common humanity with people I might earlier have dismissed as “different.” An important effort for all of us in today’s America.