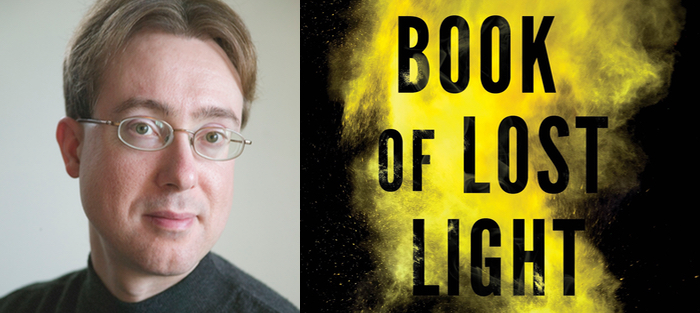

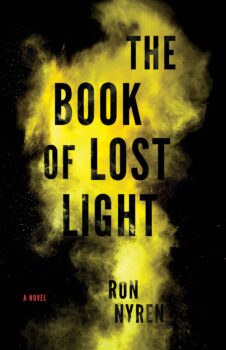

When I suggested to Ron Nyren that we have a conversation about his absorbing debut novel, The Book of Lost Light, I realized that I could no longer remember when he and I first met. Our lives were already intertwined through several writerly connections, notably Andrea Barrett, Charles Baxter, and his spouse, Sarah Stone. Ron reminded me that he and Sarah had come to a reading I gave in San Francisco. The three of us wound up taking a walk near the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which contains a number of the remarkable Eadweard Muybridge photographs that play a vital part in The Book of Lost Light (Black Lawrence Press). Since then, we’ve kept in touch in the way writers do, around work and reading and shared passions.

The Book of Lost Light is set in San Francisco and opens with the wonderfully specific sentence, “From the time I was three months old until I was nearly fifteen, my father photographed me every afternoon at precisely three o’clock.” Soon Joseph introduces us to his widowed father, Arthur, and his cousin Karelia who, while still a child herself, comes to take care of him. Arthur, inspired by Muybridge, begins his photography project, but he has met his match in Karelia, who is equally stubborn and wonderfully inventive in trying to free Joseph from his father’s demands. Then all their lives are transformed by passion and by the great earthquake of 1906.

Interview:

Margot Livesey: I love how much your novel teaches me about the early days of photography, and I love how deftly you integrate plot and character, embodying each person’s individual complexities, illusions, and virtues in their actions, even as the events move forward urgently. Arthur constantly jeopardizes his family to pursue his art. Did you realize when you began that this was going to be a novel of obsession?

Ron Nyren: I had written a short story about a boy photographed by a stranger, and I was thinking about expanding it into a novel, but something about it didn’t feel satisfying. Then I began to wonder: “What if a man was photographing his son once every day of his life from birth onward?” That seemed like the kind of obsession that could drive a whole book.

All three of the siblings in your wonderful new novel, The Boy in the Field, develop their own obsessions after they find an injured boy lying unconscious in a field, propelling each of them into a different kind of risky pursuit. The initial mystery—what happened to the boy—opens up into the multiple mysteries of how these three children will change the direction of their lives, now that they’ve glimpsed what lies underneath the apparent stability of their suburban middle-class life. I’ve been reading and loving your novels for years and also have learned so much from your brilliant collection of craft essays, The Hidden Machinery. Did writing your craft essays change your approach to your own fiction?

Thank you for asking. Writing in the shadow of The Hidden Machinery, I was acutely aware of the advice I was giving to other writers. I was particularly haunted by what I’d said about how a scene should always have a subtext and about a novel needing both long and short lines of suspense.

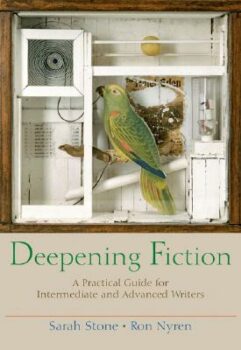

Before we talk more about photography and your novel, can I ask about the role of your wise and companiable book Deepening Fiction (co-authored with Sarah Stone), which came out in 2004. Did you also find yourself trying to follow your own advice?

Before we talk more about photography and your novel, can I ask about the role of your wise and companiable book Deepening Fiction (co-authored with Sarah Stone), which came out in 2004. Did you also find yourself trying to follow your own advice?

In my twenties, I was against the idea of “plot” because it seemed conventional and artificial, but as Sarah and I wrote Deepening Fiction, and as I started writing this book and studying how my favorite novels worked, I gained a new appreciation for classic plot techniques. I reread one of my favorite novels, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, to see how she pulled it off without a plot, and discovered that it actually had a dramatic, classic story structure—I just hadn’t noticed it the first time around because of the beauty of the language and the atmosphere and the narrator’s observations. That plot arises from the characters’ natures and differing views of the world.

Ironically, as a child, I wrote and drew a series of comic books about Super Ant (a character I borrowed from my oldest brother’s own comic books), and these had very traditional, heroic plots. My first love as a reader was science fiction/fantasy novels, and that’s where I came to appreciate books that took a speculative approach and investigated ideas. But when I encountered contemporary short stories in college, I began writing more realistic stories, though still often with a tinge of the fantastic.

How about you? Where did writing start with you, and how did it change over time?

A Super Ant comic book sounds great. One of my favorite books was about Percy the Bad Chick who ends up ruling the farmyard, and my first stories, I was probably seven or eight, were mostly about animals. But once I began to have more homework at school, I stopped writing. At university the closest we came to contemporary literature was Virginia Woolf, who was fascinating but intimidating. After I graduated, I went traveling for a year with my boyfriend, who was writing a book. I got bored watching him and started writing a book of my own: a novel. It never occurred to me that writing was something I could study.

Did you go directly from college to an MFA program? What made you decide to put writing at the center of your life?

After college, I thought, “The only place I’ve lived is Connecticut, and the only thing I know how to be is a student.” I’d always wanted to be a writer, but I felt I didn’t know enough about life. So I worked at a nonprofit arts organization for a year, saved up, and then moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. I told myself if I could write four hours a day every day, then that meant I could be a writer. I’m not sure where I got that from. I did manage for several months, until my savings ran out and I had to get temp jobs. In retrospect, those were some of the most terrible stories I ever wrote, because I was trying to imitate the stories I was reading in literary journals.

What helped was becoming part of a couple of writers’ groups and joining the staff of a local literary zine, Furious Fictions: The Magazine of Short-Short Fiction. I still had a hard time making my own stories feel finished. After five years in the Bay Area, I went to the University of Michigan’s MFA program, where I had wonderful teachers and a very strong cohort, and where I met Sarah. Knowing about craft helped a lot, but getting used to the sheer amount of revision a story takes helped even more.

I too was slow to grasp that revision was an essential part of writing; it’s very rare for a work of fiction to emerge fully formed. After Michigan, you and Sarah settled in the Bay Area. Did you teach? Or return to Furious Fictions? Or…?

Right after Michigan, I spent two years as a Stegner Fellow, working with terrific writers and teachers. So that was a great gift. I was primarily working on short stories, but I also started researching and taking notes for The Book of Lost Light. At the same time, I began freelancing, writing about sustainability, architecture, and urban design.

Right after Michigan, I spent two years as a Stegner Fellow, working with terrific writers and teachers. So that was a great gift. I was primarily working on short stories, but I also started researching and taking notes for The Book of Lost Light. At the same time, I began freelancing, writing about sustainability, architecture, and urban design.

Not too long after I finished the Stegner program, Sarah and I became part of what is now a very longstanding writer’s group with Ann Cummins, Lisa Michaels, Cornelia Nixon, Ann Packer, Angela Pneuman, and Vendela Vida. Our friend the poet Nancy Johnson was with us for years until we lost her. Ann Cummins’ husband, blues musician S.E. Willis, joined us, and then Ann Packer married novelist and screenwriter Rafael Yglesias, who became part of the group as well. So writing for me has always been part of a conversation with others. And Sarah and I have only officially co-written one book, but we help each other with every draft we write.

What a fantastic group. I think one of the best reasons to get an MFA is to find writers for whom one can be a good reader and who, hopefully, can reciprocate. Could you talk about the genesis of the novel?

My initial premise—a man photographing his son every day of his life—raised further questions. What sort of man would do this, and why? I made Arthur a protégé of Eadweard Muybridge, seeking to expand Muybridge’s pioneering work in the photography of motion to the dimension of time. How would growing up at the center of such a project affect the son? I imagined he would grow up with a theatrical streak. As I thought about who else might be in the family, I gave Joseph an older cousin, Karelia, who raises him, views the project skeptically, and becomes a photographer in her own right with a very different philosophy.

And as soon as I understood when it would take place, I knew I had to include the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Of course, I went down many blind alleys. But over the decade and a half that I worked on it, I never lost my fascination with the project.

You said that Arthur and Karelia have very different philosophies of photography. Could you say more?

Arthur was inspired by Muybridge, who took more than 100,000 photographs of humans and animals in motion in the 1880s. While researching other photographers of the era, I came across the pictorialists, whose approach seemed like the opposite of Muybridge’s and Arthur’s attempt to document physical reality—the pictorialists manipulated negatives and prints to make photographs that expressed their inner visions. I knew I wanted a pictorialist to become an influence on Joseph, and eventually gave that role to Karelia, who learns from Arthur but then turns elsewhere for inspiration. Arthur’s and Karelia’s worldviews clash, and Joseph is torn between them, sometimes the peacemaker, sometimes allying with one or the other.

And even as a young boy he does an amazing job of negotiating between these two difficult people. For me the opening chapters have an almost fairy-tale like quality, which is reinforced by the many stories Karelia tells. Later, a book of Finnish fairytales, the Kalevala, plays an important role. Did you have any specific tales in mind as you wrote?

I gave my protagonists a Finnish heritage as an homage to one of my favorite writers, the Finnish author Tove Jansson. But I could hardly have Joseph growing up reading her Moomin books, because she wasn’t even born until 1914. So in researching what myths or tales Joseph might have grown up with, I came across the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic poem, compiled by Elias Lönnrot from oral folksongs he collected in the 1800s.

My thought was that Joseph, with his theatrical streak, would grow up performing these stories, and that they might serve as fodder for plays the earthquake refugees would later put on. It was only in retrospect that I realized that my story had echoes in some of the Kalevala tales—Arthur has certain commonalities with Wainamoinen, an ancient bard with a magical voice at the heart of the Kalevala, for example.

Since my time at Furious Fictions, I’ve loved Yasunari Kawabata, whose “palm of the hand” stories and novels, like Thousand Cranes, have a melancholy fairy-tale like atmosphere. Helen Oyeyemi’s amazing Mister Fox, in which characters retell the Bluebeard story to each other multiple times with endless inventiveness and intention, inspired me to have my characters writing Kalevala plays in sometimes pointed ways for each other. And in college, I fell for Bruno Schulz, whose Street of Crocodiles describes the magical, eerie childhood of another Joseph growing up with an eccentric, driven father.

I’ve heard you talk a bit about reading and rereading Willa Cather. I see her honesty and moral lucidity in The Boy in the Field. What writers did you most love as a young writer, and what writers have come to matter to you over time?

I grew up reading all the books in my father’s bookshelves that I could reach: the Brontes, Evelyn Waugh, George Orwell, Robert Louis Stevenson, and T. E. Lawrence’s to me utterly mysterious The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. In my twenties I spent a good deal of time in Toronto and read wonderful work by Carol Shields, Alice Munro, Margaret Lawrence, Marian Engels, and Michael Ondaatje. Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook was revelatory; it suggested to me that a novel could come much closer to real life than I had imagined.

I grew up reading all the books in my father’s bookshelves that I could reach: the Brontes, Evelyn Waugh, George Orwell, Robert Louis Stevenson, and T. E. Lawrence’s to me utterly mysterious The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. In my twenties I spent a good deal of time in Toronto and read wonderful work by Carol Shields, Alice Munro, Margaret Lawrence, Marian Engels, and Michael Ondaatje. Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook was revelatory; it suggested to me that a novel could come much closer to real life than I had imagined.

I was writing stories at that time, but it didn’t occur to me that I might do research, so my choice of material was sharply limited by what I already knew. It was thrilling when I discovered that I could know more. Nowadays research is one of the great pleasures of writing fiction. The Book of Lost Light must have required research. Did you enjoy it? Did it open new and surprising doors?

I loved researching this book, finding out about chronophotography, pictorialism, the 1906 earthquake, and the artists of the time. I spent many happy hours in the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley reading journals and letters as well as amateur plays that Berkeley residents wrote and performed for themselves in the early 1900s. The Berkeley Historical Society was kind enough to retrieve 1906 issues of the Berkeley Gazette from the attic so I could page through the day-to-day developments after the refugees started flooding across the bay to stay with residents.

I love how, in The Boy in the Field, your protagonists each have their own distinct worldview and trajectory. What was your own process of discovering the characters and story for this novel?

For me the novel began with the opening scene, three siblings walking home from school and finding a boy who’s been wounded in a field. In figuring out their characters, I was guided by my belief that this event is a fault line; afterwards each will go on a quest. I didn’t feel that the three quests had to be comparable, only that they had to be absorbing. At the same time, I was aware that I’d written what would normally be the opening of a mystery novel. The three teenagers are the main characters, but in the background a detective is trying to solve the crime.

One of the siblings, Duncan, becomes increasingly drawn to painting and, when he asks his art teacher how he can “make pictures where a lot is left out but people fill in the details,” he is loaned a book of Morandi’s paintings of bottles. You write Duncan’s experience of looking with such beauty and believability. Can you talk about the role that Morandi and Duncan’s own paintings play in this novel?

In 2008 I saw a gorgeous and heartbreaking Morandi show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Later, I read an essay by the Italian novelist Umberto Eco about encountering Morandi as a teenager. When I thought about a painter whom Duncan might respond to, Morandi, whose work hovers between realism and something else, seemed the perfect choice.

I love the idea of work hovering between “realism and something else.” As always, I’m learning so much from you. What is the relationship now between your writing and your teaching and everything else that you give to writers?

When I finally entered a classroom, after nearly a decade of waitressing, I found it very stressful. I spent twenty or thirty hours preparing for a ninety-minute class. But when my terror began to abate, I discovered that I liked talking about things that mattered – Baldwin! Munro! – as opposed to asking people how they wanted their steaks done. I hope that teaching has made me a better teacher and a better writer. Do you teach? Do you find it enlarges your work?

The majority of my work is still freelance writing and editing. But I have also been teaching fiction writing at Stanford Continuing Studies since 2011. I love helping students find new layers to their work and seeing their imaginations unfold in so many different ways. Reading and thinking about so much work in progress has helped me gain a better understanding of what makes a story feel like a story, as opposed to a sequence of interesting events.

And that is one of the great satisfactions of The Book of Lost Light; it is full of interesting events yet much larger than the sum of its parts. You said earlier that you had worked on the novel for over a decade and a half, so I wonder how it feels to have it out in the world, beyond the reach of revision. Are you already at work on something new?

It’s been a great experience to work with my editor Diane Goettel and Black Lawrence Press. And I feel happy to have the book out in the world. More recently, I’ve been writing short stories and the beginnings of a new novel. The characters come directly from myths, but once again, I’m telling the story of a son caught up in his father’s wild projects. My own father was gentle and tremendously kind, treasurer of the local garden club, and a pillar of his church, so I don’t know where any of this comes from. Some people write directly or in a disguised way from life, but I don’t seem to. After this conversation, I’d like to adopt your idea of work that “hovers between realism and something else.” That’s the territory where I want my writing to live.