I was first introduced to Megan Mayhew Bergman’s work through her debut short story collection, Birds of a Lesser Paradise. Immediately taken in by its insightful and droll observations about our daily lives and how we, or anyone, actually manage to live in them, it remains a favorite of mine for its extraordinary ordinariness.

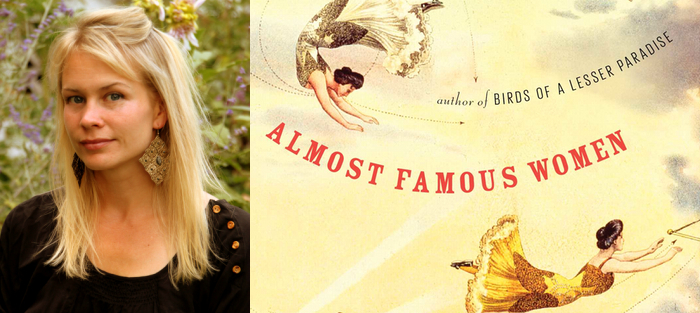

Her second collection, Almost Famous Women (Simon & Schuster), which came out in January, again works to capture and explore the heroics present in the quotidian through its vibrant protagonists–women on the edge of the spotlight like Norma Millay and Allegra Byron whose last names you might recognize even as their first names hover and fade in obscurity. Women like Romaine Brooks and Beryl Markham who attempt to live their lives as authentically as possible often against great odds.

One of the collection’s epigraphs comes from Janis Joplin: “You can fill up your life with ideas and still go home lonely.” Bergman’s heroines are many things–strong, reckless, kind, undeterred, and indeterminable–but they all know what it’s like to go home lonely. That loneliness is at the core of AFW, and it is one of the book’s greatest reading pleasures and sorrows all at once. Magically.

Megan Mayhew Bergman is the author of Birds of a Lesser Paradise and Almost Famous Women. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Best American Short Stories, New Stories from the South, McSweeney’s, Tin House, and Oxford American, among other publications. She writes a sustainability column for Salon and lives on a small farm in Vermont with her veterinarian husband, two daughters, and many animals.

Interview:

Olivia Postelli: I think it’s a truth universally acknowledged that most writers start out as avid readers, especially during their childhood and adolescence. Does that hold true for you? Any childhood favorites that you’ve passed down to your daughters? I always loved The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. And Harry Potter, of course.

Megan Mayhew Bergman: I think that as an adult reader I’m always trying to get back to that feeling I once had while growing up at the beach–a fresh, yellow-spined Nancy Drew in hand. I’d take it everywhere–ocean side, then thumbing through a few pages at lunch, reading in the car on the way to dinner, reading at the dinner table out a restaurant, and then staying up too late at night to read in the dark. I love being consumed by a book.

I was always moved most by “tomboy” characters: Nancy Drew, George Fayne, Jo March, Scout Finch, and so on. I liked the cropped-hair, skinned-knee girls. I wasn’t one all the time, but I wanted to be. I felt that they were living honestly.

I now have two young daughters that I read to, and I love seeing what in literature lights them up–the prose, the characters, even the darkness or a sense of mystery. All that matters to me is that something, anything lights them up!

How was writing this second collection different than writing your first, Birds of a Lesser Paradise? Did you know going in that it was going to be another collection as opposed to a novel?

I think you have a certain exuberance and bravery with your first book that’s hard to capture again. I wrote Birds of a Lesser Paradise not knowing that it would be published–its raw honesty is one of the attributes that makes it successful, I think. With Almost Famous Women, I wrote with more intent and practice. It’s a shrewder, tighter book.

I love the idea of your first book coming from a certain kind of… maybe moxie is the right word? Like facing this challenge of writing a book with a sort of energetic know-how despite never having written a book before. You mentioned “exuberance.” What else about writing, either this second book or writing in general, makes you feel exuberant? Not the same as that “first book rush,” but something close to it?

Exuberance is a tricky feeling–it’s short-lived, dangerous, addictive. And yet chase it as I may, I’ve found I really only get hold of it by accident–traveling alone and finding myself with the sun on my skin, laughing with my daughters, running with my dogs. But with writing the second book, I suppose the feeling of exuberance comes over me whenever I pause and reflect on the fact that I worked hard and accomplished my dream, as trite as it sounds. But that allowance of saying to yourself: I did it. That’s its own form of exuberance.

How did Almost Famous Women come together as a collection? Did one of the stories come to you first, and then you followed that thread into the other stories? Or did you begin with the concept–“heroines born in proximity to the spotlight”?

How did Almost Famous Women come together as a collection? Did one of the stories come to you first, and then you followed that thread into the other stories? Or did you begin with the concept–“heroines born in proximity to the spotlight”?

I was writing AFW in my head for a long time before I admitted it was a book. I was forming the theme subconsciously. I’m an intuitive writer. I’d say I was an expert on underdog heroines before I was an author of their stories. I read, researched, imagined, and obsessed, and then realized I had compelling narrative ingredients.

The collection combines historical, contemporary, and, in the case of “The Lottery, Redux,” speculative fiction. What was the research process like, especially since many of the characters must have been difficult to track down in historical records and archives?

The research process started out as, simply speaking, my reading life. I was following my intellectual curiosity first. We are lucky that some intrepid biographers like Meryle Secrest conducted original research before it was lost to time–and yet, for many of the women in my book, one already had to enlist the imagination to fill in the holes–that is how research turned into fiction writing.

“The Lottery, Redux” is an outlier in the collection as it is a reimaging of Shirley Jackson’s famous–infamous–short story. The author’s note mentions it was written for McSweeney’s as a “cover story” of a classic. How did it find its home in AFW? How would you say it differs from or coincides with the rest of the stories?

Shirley Jackson looms large for me, as I live just outside of Bennington and pass the house she lived and wrote in often. While she is famous to writers and fans of literature, I doubt the average person on the street knows her name (unfortunately). When I reimagined her story for McSweeney’s, I wanted the story to have strong female characters–so you see an island in the future with a matriarchal lineage. I believe that’s how it fits in thematically.

You mention that Shirley Jackson looms large for you (in a physical sense and as an influence). Who else looms large for you as an influence? On this collection in particular or in general? Whether it’s other writers or people from the non-writing sphere of your life.

Right now, the people that loom largest for me are adventurous women who lived as they wanted to–authentically if you will, though that is a bit of an unfortunate buzzword. But I’m mostly enchanted by brave and unusual people–I love meeting them, feeling inspired–women like Liz Clark, who sails the Pacific solo. I am so much less interested in female martyrdom than female heroism.

Although historical figures both appear and star in many of the stories, it’s very obviously intended as a work of fiction. Do you think the fiction of it allows you to tell the truth, or a truth, about women’s experiences in a different way?

Excluding hard and fast facts, like dates, I think truth is an abstract notion, even in memoir. When we represent experience, including our own, we’re already engaging with fiction, in my opinion. But representing experience is an important part of art. So I was interested in keeping my intent “true”–but most important to me, artistically and thematically, was representing a passionate woman’s interior landscape. I didn’t want to romanticize experience or character. I wanted to talk about risk-taking, sacrifice, hard choices, and women who were pursuing careers and lives, not just vanilla romance.

Can you talk a little more about how “representing experience is an important part of art”? Do you think writers have a responsibility to represent diverse experiences? To give or lend their voices to characters and experiences that might not otherwise have a platform?

I try not to make rules for my fellow writers–I don’t enjoy them myself. But I do think it’s valuable when diversity is represented more in fiction, on the masthead and on the page. Because reading fiction develops empathy, I think giving readers access to diverse experiences and lives is critical.

Although every story contains an “almost famous woman,” not every story is narrated by one. I’m thinking particularly of “Who Killed Dolly Wilde?” and “Saving Butterfly McQueen.” In the latter story, the narrator, Elizabeth, only meets the actress once, but that encounter changes her life. How did Elizabeth come to narrate that story? A story as much hers as it is Butterfly McQueen’s.

I thought that if I wrote AFW with a first-person female narrator in every story, the book would come across as if it was in all caps. These women were intense and ferocious. Sometimes, telling the story from the angle of a lover or servant was a way to illuminate the almost famous woman’s character.

I was fascinated by the orbit of fame, the way it influences a power dynamic, or the way we are so quick to be reverent of greatness. But greatness fades, or is forgotten, or at times underappreciated. I wanted to play with those ideas, too.

The book is preoccupied with moments of transition and awareness (hence a lot of flash fiction). Lucia throws the chair and it ends up being a turning point in her lifelong hospitalization. The Internees feel human after years of incarceration and inhumane treatment. For Elizabeth, the encounter with Butterfly strips her blinders off, leads her to a powerful line of questioning.

Georgie, in “The Siege at Whale Cay,” is one of my favorite characters in the collection. When she says, “And important people made you feel not normal, but unimportant,” that struck me as applicable to every woman in the book in some way or another. Do you think that’s at the heart of these stories? That sense or feeling of being unimportant?

Georgie, out of all the characters in the book, is the one I feel most personally invested in.

You are right in recognizing my preoccupation with the way we value people, particularly women.

I think one of the things I love most about Georgie is that she knows, from the beginning, that “life with Joe never lasts.” She knows her time on the island is temporary, but it doesn’t mean she feels what happens to her there any less intensely. I’m not sure if I can articulate it very well, but there’s something about the way Georgie feels things, how she takes things in and rationalizes and internalizes them. Is that deciphering of emotion something you thought about while writing her?

I think one of the things I love most about Georgie is that she knows, from the beginning, that “life with Joe never lasts.” She knows her time on the island is temporary, but it doesn’t mean she feels what happens to her there any less intensely. I’m not sure if I can articulate it very well, but there’s something about the way Georgie feels things, how she takes things in and rationalizes and internalizes them. Is that deciphering of emotion something you thought about while writing her?

I’m fascinated by the way we think through what we “should do” and what we actually will do, or are capable of doing. If we knew more of what we wanted in life, or were braver or less lazy or better supported wouldn’t this sort of rationalization be easier? What would we do if we weren’t afraid? I love that question. I know it’s kind of “woo woo,” but I love its provocative nature, its difficulty.

In the author’s note, you write “the world has not always been kind to its unusual women–though I did not intend these stories to serve as cautionary tales.” I found that many of the stories were celebratory and funny even as they were wistful or downright sad. How would you describe the book’s tone? Is there any story in particular that you think manages to strike the balance between celebratory and sad?

I certainly wanted it to be both celebratory and sad because I think most lives lived well and fully have that tone. Anything fully melancholy betrays the victory of living out a risk or goal, and anything fully celebratory undermines the sacrifices made.

Finally, in “Hazel Eaton and the Wall of Death,” Hazel asks herself: “what makes you empty and what makes you full”? Is that question one you think many of your heroines entertain? It seemed especially poignant to me because I know, personally, as a woman, that my answer to that question–no matter what the answer is–is never exactly “right,” never exactly what the asker wants to hear.

It is one of my favorite lines from the book, and a question I ask myself often. There are so many ways to spend one’s self, and I think many of my heroines must have asked it, perhaps during long car rides or sleepless nights. There is an Oscar Wilde quote–I mean, let’s be real, there’s an Oscar Wilde quote for everything–that says, “To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.”