To get to some of the craft issues in the book, I was interested in the choice to omit quotations marks. It wasn’t difficult to see who was speaking, but I found as I was reading that the lack of quotations marks made the text run together in ways that produced slight ambiguities about things like was this scene happening in someone’s mind or was it happening out loud.

Leaving out quotation marks is something I started doing in writing the stories in The Train to Lo Wu, and ever since I wrote that book I haven’t gone back to using quotations marks. Now it’s become a stylistic paradigm—everything I write comes out that way. For me it’s no longer about why not use them, it’s about why add them? If I feel my text the way it is, what do quotation marks add? In some cases what you say is right, they add clarification, and they make a sharper divide between narration and speech. When I started leaving them out, a lot of that decision had to do with the fact that I was writing about Hong Kong, which was a space that felt very dreamlike and unreal, and I wanted to text to represent that kind of dreamlike quality. And I was also looking for the first time at Chinese, at that time I wasn’t reading Chinese with any fluency, but I was looking at Chinese writing, and by and large it doesn’t use quotation marks. I was also reading writers like Michael Ondaatje, who doesn’t use quotation marks.

It just so happened that at that time I was reading a lot of writers who don’t use quotation marks or who use some other way of representing dialogue, like a lot of Irish writers use dashes, and Nadine Gordimer uses dashes. The use of punctuation for dialogue is very culturally specific. In the UK they use one quotation mark, here we use two, in Ireland many times it’s dashes, in some European countries they use those little arrows (<

>), so I gave up using quotation marks for a specific stylistic reason, and now that sense of representing or narrating a text so that it has a dreamlike quality, or a quality where the speech and the narration blur into one another is second nature. I like that sense of ambiguity, and of sometimes having one shade into the other. I find something almost ugly about quotation marks.

Connected to that issue, I was interested in the number of monologues in the book—they’re sometimes part of dialogues, but they’re places where the characters rant, and yet it took me a second read of the stories to recognize that they shared that similarity; these so-called monologues are so different because they’re in different characters’ voices. Can you talk about how you decide when it’s time for a character to let loose?

It’s a great question because we’re taught not to let characters do that, to run on in that way. It’s breaking workshop rules. For me it emerged naturally out of the situations of these stories, and of course a quality of people who are zealots and ideologues and fanatics of one kind or another is that they tend to have a hard time having conversations that are actually conversations. They tend to have conversations that are pretexts for rants. Some of the characters in the book, like Rafael in “The Answer,” just deliver speeches. He’s only listening in order to find an entry point for his next speech. It was necessary for some of these stories for there to be that quality. But I’m also drawn to stories where characters start talking and don’t talk when they’re supposed to. They keep talking and suddenly they reveal something about themselves that they then have to correct or expand upon. For example, in “The Call of Blood,” a male nurse is taking care of the mother of a Korean woman, and this middle-aged daughter goes on about the terrible thoughts she has. And the longer she talks the more she starts inhabiting these thoughts. That’s the kind of thing that really happens. If people are allowed the space to go on, they slip and they say very unpleasant but perhaps very truthful things if they speak longer than social conventions allow.

So it’s a way of developing characters that’s very different from gleaning bits form the story—instead we get this chunk of information.

Exactly. I also really like oral storytelling, and I like it when characters tell stories in their dialogue, whether about themselves or other people. I like that quality of oral narration and enclosing it in the written narrative. I like that contrast and that tension.

To talk specifically about your story “The Answer,” I wondered how you crafted the structure. The narrator is nostalgic, looking back in time, and we get the story of his relationship with Rafael, and then we catch up to the present, and then you have these appendices at the end. It’s an interesting way to give the story an end—we’re no in doubt about what has happened to Rafael.

I thought that story had to have appendices. I had a struggle with an editor once who really insisted on taking them out, and wanted the ending just to have space breaks between the sections. But I wanted the appendices to divide them from the story as a concrete unit, which ends with Rafael’s departure, and the half-kiss/half-embrace that they share, and then these parts that don’t quite belong in the story that explain what happened to Rafael. But there’s the story, which takes place in 1993, and then there are all these other pieces, and the story doesn’t really try to assemble them, and that’s part of the point. The appendices are not integrated into the story, and so the story doesn’t have a sense of organic wholeness.

Because the narrator isn’t really sure what to think about his own story?

That’s right. In fact the story follows very actual events very closely. When I was at Yale in 1993 there was a young Latino student who was a devout Muslim, and he disappeared in October of our freshman year, so he was only on campus for about six weeks. Nothing was ever heard of him, and then in 2002 there was a short article in the New York Times that reported that this student’s name had been found on a list of Taliban combatants that was found in a safehouse in Kandahar. So apparently he had been present or even fighting in Afghanistan, and maybe he died or maybe he’s still there, nobody knows. That was all that was heard of him. The story came out of those two incidents, but the whole story lies in between those two points. In “The Answer” I try to fill in some but not all of the details, because there’s a tremendous amount that can’t be known.

The narrator in the story “Sheep May Safely Graze” describes himself as being “afflicted with compassion,” which is both a lovely turn of phrase, but which could also apply to many of the characters in the book. What made you think about pairing fundamentalism with compassion?

Sometimes our compassionate impulses are also violent impulses. It’s very difficult for anybody to accept that. In some ways it’s especially difficult for Americans, because we’re taught to be very optimistic about human nature, and especially optimistic about charity, and good works for the community. We’re a society that thrives on civic organizations. There is a feeling of outrage about things that personally affect us, that the personal cause can be violent, and that makes some kind of sense to people. But sometimes when people have a purer state of altruism about something that doesn’t affect them directly, the abstraction of that can turn into a kind of violent rage because it’s so depersonalized. And sometimes that abstract altruistic urge or state strikes some deep chord within us for some completely unconnected reason.

In some sense that’s what happens in “Sheep May Safely Graze.” You have a man grieving over the death of his daughter, and he’s lost his bearings as a human being, and then this altruistic urge comes from outside, and because he’s so emotionally unstable, it guides him toward an extreme action, because he feels there’s no other outlet for his emotions. I think that happens more often than we think, and the reason it doesn’t usually result in some kind of violent act is because we have other social norms and pressures that prevent us from acting.

But I also think the relationship between altruism and violence is an essential aspect of American foreign policy. The fact that we want to do well by people to whom we have no other connection often results in us doing something violent that has unintended consequences. That was true to some degree in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea. The sense of being on a moral mission is a very dangerous state. In the case of the US it’s not so much fundamentalism as it appears in religious absolutism, but a cultural absolutism—a sense that things can only go one way, and if they’re not [headed that direction] then we have to correct the events to make them accord with our sense of the natural order of things.

One of the most impressive things about the book is the way you inhabit all these different voices. Do you have any advice for younger writers who are considering writing someone who is very unlike them, especially someone of a different race or ethnicity?

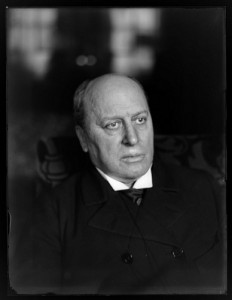

Henry James

My advice is contradictory. Part of my advice is do your homework. And part is forget about your homework and trust your instincts. Henry James has a passage where he talks about how an Anglo-American novelist can write about French characters. He says that another writer he knew once saw a French couple gesture in a way that taught him all he needed to know to illustrate Frenchness. So obviously that sounds great, but it’s very dangerous because you could be generating stereotypes. The way that I’ve always approached it is to try to be grounded in the details of that person’s imagined life as closely I possibly can, usually by knowing someone like the character. After a certain point you’re in the story just trusting your naïve human insight, and then when you revise, checking it if necessary, and checking the details with people who would know better. So, trust, but verify, but it’s probably the other way around: verify and then trust yourself.

The courage to do that is hugely important, and it’s not taught, and maybe for good reasons, but we have a very powerful cultural norm that discourages young writers from doing this. There’s much more permission to go back in time and write the story of an 18th century washerwoman than there is to write about somebody who lives in Mogadishu now. And I have to say I find that very problematic. I think the huge super-abundance of historical fiction being written right now is partly a matter of just plain fleeing from the complexities of the present. That’s a real problem, because it’s not that there isn’t lots of great historical fiction, but in some ways it does a disservice to the present, and it also encourages people who like to say that the only art form that can meaningfully interact with the present is nonfiction.

If too many fiction writers flee the present then the people who represent the present are going to be other writers of nonfiction, and nonfiction is fine and wonderful, but it’s very painful to me to see this preference [by fiction writers] for what I think of as rather exotic material. For one thing it’s very repetitive. There are a lot of novels being written about World War II. And I find it very striking that there are a lot of writers younger than I am, which is to say that if they know anyone from that period, that person is, very very old, and they might never have met anyone who was alive during WWII. They’re writing about WWII, and I don’t have any problem with that per se, but there is this fascination with other times and places in the past and no fascination or interest in what life is like right now in Mexico City, or what life is like right now in Cincinnati, or Philadelphia. At times I’m afraid that there’s something very unreflective about that.

What else are you reading right now?

I’m reading as much of E.L. Doctorow’s corpus as I can because I’m writing a review of his New and Selected Stories. I hadn’t read a lot of his work except for The Book of Daniel and a couple of other books, so I’m trying to cover the major bases of his career, which is interesting. I’m also reading one of Jose Saramago’s early novels called The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reyes, which is this amazing masterpiece of a 20th century novel (talk about a historical novel!) set in 1936 in Lisbon. It’s a novel that is very out of time. A lot of it involves the ghost of Fernando Pessoa. It meditates on the entire 20th century. The writing is incredibly beautiful, and it comes across in the translation. Many times reading in translation you feel like you’re only getting an approximation, but here the prose in so beautiful that either it’s very faithful to Saramago or the translator was incredibly gifted.

I’ve also been reading a Mexican novel from the ’50s called Pedro Páramo. It’s by Juan Rulfo, and it’s the only novel he ever wrote. It’s called the jumping off point for all magic realism, apparently Garcia Marquez memorized it before he wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude. It’s very short and it’s astonishing because it’s so surreal, and it’s about a live visitor to a town in which everyone else is dead. It’s narrated on so many levels simultaneously that it’s just about impossible to find your way in it from page to page. It is chronologically linear, but that linearity is almost beside the point because so many voices are coming in from so many different places, including the voices of ghosts. It’s fascinating and I’ve never read anything like it. I’m also reading and teaching Mary Gaitskill’s short stories; I love her new book of stories. I love how different it is from her earlier work, like Bad Behavior, which is better known. I think somewhere in her career she did a 180 from a minimalism to an emotive maximalist, and I really admire that.

I’ve also been reading a Mexican novel from the ’50s called Pedro Páramo. It’s by Juan Rulfo, and it’s the only novel he ever wrote. It’s called the jumping off point for all magic realism, apparently Garcia Marquez memorized it before he wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude. It’s very short and it’s astonishing because it’s so surreal, and it’s about a live visitor to a town in which everyone else is dead. It’s narrated on so many levels simultaneously that it’s just about impossible to find your way in it from page to page. It is chronologically linear, but that linearity is almost beside the point because so many voices are coming in from so many different places, including the voices of ghosts. It’s fascinating and I’ve never read anything like it. I’m also reading and teaching Mary Gaitskill’s short stories; I love her new book of stories. I love how different it is from her earlier work, like Bad Behavior, which is better known. I think somewhere in her career she did a 180 from a minimalism to an emotive maximalist, and I really admire that.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a novel about racial reassignment surgery. I’m also working on new stories, essays and reviews of fiction, and some translations of Buddhist texts. I’m busy.