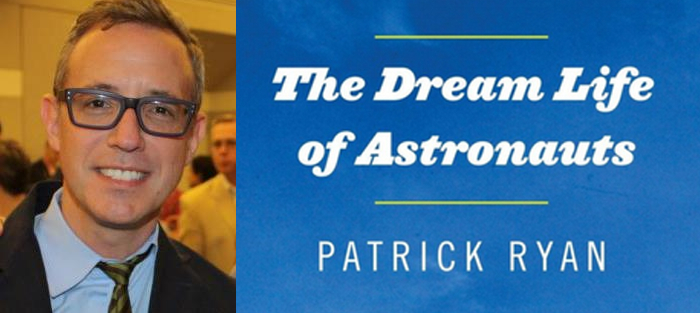

Earlier this month, the revered Brooklyn-based magazine One Story announced that while cofounder Hannah Tinti takes an extended sabbatical, Patrick Ryan will step into the role editor-in-chief at the magazine. It is a fitting final flourish for what’s already been an exceptional year for Ryan.

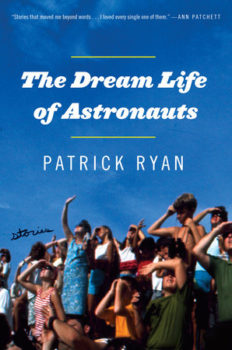

When Ryan’s short story collection The Dream Life of Astronauts (The Dial Press) was released in July, reviewers quickly lined up to praise Ryan’s natural storytelling gifts, his deft touch with humor, and the sense of place in his stories. Rebecca Makkai raved in the New York Times Book Review and Maureen Corrigan gushed on NPR’s Fresh Air.

Set in 1960s and 1970s Cape Canaveral, the collection provides fertile ground to point to Ryan’s knack for building narratives that feel familiar and inviting, yet prove consistently surprising. His stories have an elegant, seemingly effortless flow that lulls the reader into laughter before handing out the gut punch. The Dream Life of Astronauts has earned Ryan quite a list of fans: while Pulitzer Prize-winner Richard Russo calls Ryan “a very funny, smart and gifted writer,” Ann Patchett has noted his stories are “comedies that can just as easily be read as tragedies. They are stories of isolated individuals bundled together into the families that define them.” Ann Beattie perceptively mentioned how Ryan’s narratives “launch you right out of your comfort zone” as they are “filled with so many surprises and with so much yearning that it’s palpable.”

The Dream Life of Astronauts is Ryan’s fifth book, following his novel-in-stories, Send Me (The Dial Press, 2006), as well as three novels for young adults: Saints of Augustine, In Mike We Trust, and Gemini Bites. His fiction has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, Tin House, One Story, Catapult, Crazyhorse, The Iowa Review, The Yale Review, and elsewhere. His nonfiction has been published by Granta and has appeared in Tales of Two Cities and other anthologies.

Prior to his brand new gig as editor-in-chief at One Story, Ryan worked as an editor at Granta before becoming a contributing editor for One Story and editor-in-chief of One Teen Story.

Interview:

Plot? Character? A snippet of dialogue? What’s the moment when you’re done thinking about a short story and ready to begin writing it?

Oh, god, I wish it were plot. Usually it’s character. Character and a situation and a reaction to that situation, then a sense of what the next situation is, and the situation after that, and how the character is going to react to and shape those situations. (Wait—is that plot?) I don’t ever begin something without a sense of where it’s going. I don’t write in the dark. I start with character, make a loose plan, and keep it all malleable until I get to somewhere around the halfway mark, or just past the halfway mark, and can abandon my notes. By then, I usually know if a story is going to work or not.

How do you land on the point-of-view and tense for one of your stories?

The choice between first- and third-person is usually a clear one—tied to whatever my initial thought was in regards to the story. And more often than not I choose third. I find the third-person more interesting to work with, more expansive. I wrote a story in the second-person once that I only attempted because I honestly could wrap my head around why that point-of-view choice made sense, given the main character and the subject matter, and that was a fun experiment that I think was successful. The point-of-view I’ve never tried but would like to try one day is the first-person plural—so wonderfully handled in Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic. [See Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s essay “In a Shared Voice” on this subject and Otsuka’s novel.]

The question of verb tense is a little more up in the air when I write. “Up in the air” in a good way, in that I don’t ever get stalled on it. Every once in a while I’ll switch something I’ve been working on from past to present (or vice-versa) just to see how it changes the performance of the engine.

It’s interesting your often default to the third-person. In some of the first-person stories in The Dream Life of Astronauts—such as “Summer of ‘69” and “Miss America”—you take the female point-of-view. How do you arrive at that kind of decision?

I’ve always been drawn to writing from the female perspective. Coincidentally, maybe, most of the people in my life who have had a direct, positive influence on me and advised and counseled me have been women. But I don’t sit down to write with an agenda, or even with a conscious leaning toward particular subject matter. I just go to the story ideas that have sticking power in my brain, and many of those center around female characters. After Send Me came out, I was aware that while it has two very prominent female characters, I hadn’t written any of them in the first-person. So that presented itself to me as a box I wanted to break out of.

I’ve always been drawn to writing from the female perspective. Coincidentally, maybe, most of the people in my life who have had a direct, positive influence on me and advised and counseled me have been women. But I don’t sit down to write with an agenda, or even with a conscious leaning toward particular subject matter. I just go to the story ideas that have sticking power in my brain, and many of those center around female characters. After Send Me came out, I was aware that while it has two very prominent female characters, I hadn’t written any of them in the first-person. So that presented itself to me as a box I wanted to break out of.

In the first few incarnations of “Summer of ’69,” the narrator was male. When I decided to make the narrator female, all the doors and windows flew open. With “Miss America,” I have a great fondness for that story. I spent six months writing it in a time when I was very busy with my job and had almost no time to write, and the one thing I never wavered on was the decision to write it in first-person. Dani is a character who’s being given advice right and left and feels a little tugged around, but she’s not a victim, and I was glad to dive into that in a first-person voice.

Six months? Is there an average amount of time it takes you to get the first draft of a story on the page? Or amount time or drafts it takes once that first draft is completed?

I write very slowly, and I rewrite a lot as I write. It’s kind of a problem, in that I can use up what little time I have “perfecting” a scene or even a single paragraph. It’s a terrible way to work. I’ve always wanted to write the way everyone else seems to—knock out that sloppy first draft, then work on cleaning it up—but I’ve never been able to do it. I’ve thought about trying hypnosis, but I worry it might creep into other areas of my life (Crossing a busy intersection? Just do it in a reckless fashion and deal with the mess later!). That said, I’ve had a few stretches wherein I had all my time, and in that situation, I was able to write a first draft of something in about two to three weeks.

Once I finish a first draft, I set it aside for a bit, then read it aloud to myself and take no prisoners. I don’t really count how many drafts I do. I just keep going over and over it until I’m convinced I can’t make it any better. Then I show it to a couple of trusted friends, and I listen to what they have to say. Then I go back to work. All that happens before I ever send it out or let an editor see it.

While you’ve written three YA novels, you seem inordinately drawn to the short story form—even Send Me is fairly described as a novel-in-stories, right? Why does the short story form appeal to you?

While you’ve written three YA novels, you seem inordinately drawn to the short story form—even Send Me is fairly described as a novel-in-stories, right? Why does the short story form appeal to you?

Yeah, I wrote Send Me to be twelve stand-alone pieces that worked like a collage, forming one big portrait of a family. I’m drawn to the form because the stakes are very, very high in short stories. There’s not much room for excess or indulgence. Short stories need to be tight without feeling tight. Creatively, I tend to function better on a smaller canvas where I can keep an eye on what I’m doing, what I’ve done. (Not that I don’t have a novel in the works–I always have a novel in the works.)

You are the former associate editor of Granta, and are now the editor-in-chief of One Story. How has editing work by writers such as Ann Beattie, Colum McCann, Alice Munro, and Joy Williams impacted the way you not only edit your own work, but how you write your first drafts?

What I see when I read submissions are a lot of openings of stories—say, the first two pages—that are clunky or confusing or have no traction. That, in its own way, makes it intimidating to write because part of me is thinking, I’m not immune to these missteps, either. How can I be sure I’m not doing the same thing when I write? I just have to trust myself that if I’m making missteps—and of course I am—I’ll catch them by rereading a lot, revising a lot, putting in the hours.

Editing the work of established and extremely talented writers, some of them my heroes, brings with it a different kind of intimidation. With writers of that caliber, the mistakes are usually absent (either because they’ve already been swept away or they were never there to begin with), so editing them is fairly easy, and thinking about how amazing their work is when I sit down to write is daunting. But you just have to slough that off. If you invite someone to have dinner in your home, you can’t let yourself get crippled with worry that the meal you’re fixing doesn’t measure up to all the best meals they’ve ever eaten. Presumably, they’re hungry. Presumable, you’re not going to poison them. Make some food.

On a side note, I’ve had the pleasure not only of editing both Joy Williams and Alice Munro but of calling them both and suggesting last-minute edits for pieces that were about to go to print. Imagine walking home from work at 8 p.m., exhausted, and having your phone buzz because Joy Williams is calling you back to respond to the edits you mailed her (edits you don’t have in front of you but, thankfully, have memorized and can talk about while standing next to a dumpster on 13th Street). Or sitting at your desk and steeling your nerves to call Alice Munro to suggest word changes. I have rarely experienced sweaty palms in my life, but I had sweaty palms before dialing Alice Munro. She was lovely, and allowed me some additional moments to compose myself while she searched for her reading glasses.

There is such clarity and concision to your own prose, and you never show off. Have you always written this way or is this a style you’ve evolved to over your years of writing?

Thank you for saying so. Clarity and economy are very important to me. I think I started out, many years ago, trying to emulate authors I admired, which in a way was a kind of showing off. Eventually it became more important to me to tell a clear, concise, and emotionally impacting story rather than try to nail an impression. So in that way my style has evolved. When I look back at early writing of mine, the thing I wince at almost as much as the weak ideas are the flourishes. The decoration. The overuse of metaphors. All slights-of-hand to distract the reader from the trick itself. I think that’s the biggest difference: now I don’t think in terms of tricks or slight-of-hand. I trust the idea and spend my energy on rendering characters that feel real and raw in the moment.

When you began the story “Earth, Mostly,” did you have any sense that sixteen-year-old Frankie from “The Dream Life of Astronauts” would reappear the way he does, many years older and in much different shape than when last we saw him?

I did. Frankie is the character I’ve been writing about for over a decade now and can’t let go of. He’s a huge presence in Send Me (he opens and closes the book, and he appears in quite a few of the stories). I’ve published stories where he’s a little boy, a teenager, a young man, a middle-aged man, and an octogenarian. There’s one story where he’s an infant that I’m still tinkering with. One day I hope to be able to line up all the Frankie stories in chronological order and read them and experience a whole life lived out of sequence but reassembled. It will be fun to see what his arc is.

The Dream Life of Astronauts has such a pitch-perfect sense of place and time—the space-crazed Atlantic coast of Florida in the 1970s and 1980s—yet it never feels like you’re knocking the reader over the head with silly nostalgic troupes. Can you talk a little about the challenges of writing such a specific place and time without that overpowering the human narratives?

I think I was able to do that—to the extent that I did—because I grew up there and experienced what it was like for a community to live day-in, day-out without the national interest (and national pride in the late 60s and early 80s) in these giant events affecting things. We were living right in the middle of the space coast, right in the heart of the space race, but we were really just a melting pot of people who were busy working their jobs, going to school, paying rents and mortgages, mowing lawns. It didn’t feel exotic. So I didn’t want to present it as exotic for the reader.

One of the big challenges that comes with writing about a past era is avoiding all the tempting cultural references. I usually research the hell out of the time period in which something takes place and load on the cultural references—like a starving man at a buffet. Then I take out as many of them as I can. A good friend read the manuscript for The Dream Life of Astronauts and one of her notes was that I take out at least half of every TV show and film mentioned. And I did. I had to leave quite of few of them in for “The Way She Handles,” because the narrator in that story is looking back at the summer of 1974, when he was nine, and TV shows and films were a big part of his existence. But I axed as many as I could in the rest of the book. Less is more. When you write fiction, you should be flexing your creative muscles, not your Google muscles.

No matter how flawed your characters are, your stories are infused with empathy and a core of tenderness toward even the, let’s say, “less loveable” characters—such as Derek, the talent scout from “Miss America” or Billy in “Earthy, Mostly.” How do you approach writing your “villains”?

For me, the most interesting thing about villains is that they don’t see themselves as villains. I’m not talking about The Joker or anyone in the wonderful world of comics, but people we encounter in everyday life and in fiction who are jerks and bullies, creeps and opportunists. Leaches. Narcissists. They don’t see themselves the way other people see them. I go through life—both on the street and on the page—fascinated by how everyone (including me) feels justified in doing whatever they’re doing in the moment they’re doing it. Regrets later, sure. Lies and swept-over tracks, of course. But in the act of being less-than-model citizens, we all feel justified. So when I write about a character like Derek, the self-proclaimed talent scout in “Miss America,” I’m not interested in taking shots at him for being a creep; I’m interested in how he assesses himself, what he thinks he’s bringing to the table. He’s not wringing his hands and thinking, what awful things can I inflict on these teenage girls? He’s just a guy doing his best, moment by moment, and trying to get somewhere in a very selfish way.

Since the book was published this past summer and you’ve been giving readings and interviews for several months now, what has been the most surprising revelation you’ve had about your own writing because of a reader’s observation or question?

There was an interviewer who told me that my characters are more beaten down than they themselves know. That had never occurred to me, and I’m glad it hadn’t because it inches toward being a comment about recurring themes in my work and I never think about themes. I never want to think about the theme of something, going into the writing of it. But I thought it was a very interesting and true observation, looking back.

And one reviewer pulled a bit of dialogue out of the book and called it “an over-arching thesis statement, of sorts” and I think he’s right, though it hadn’t occurred to me when I wrote the lines or when I reread them in subsequent revisions, edits, copyedits, and proofreading. The lines are “There’s no end to the sickness and depravity of the human spirit. I guess that’s the good news.”