Introduction

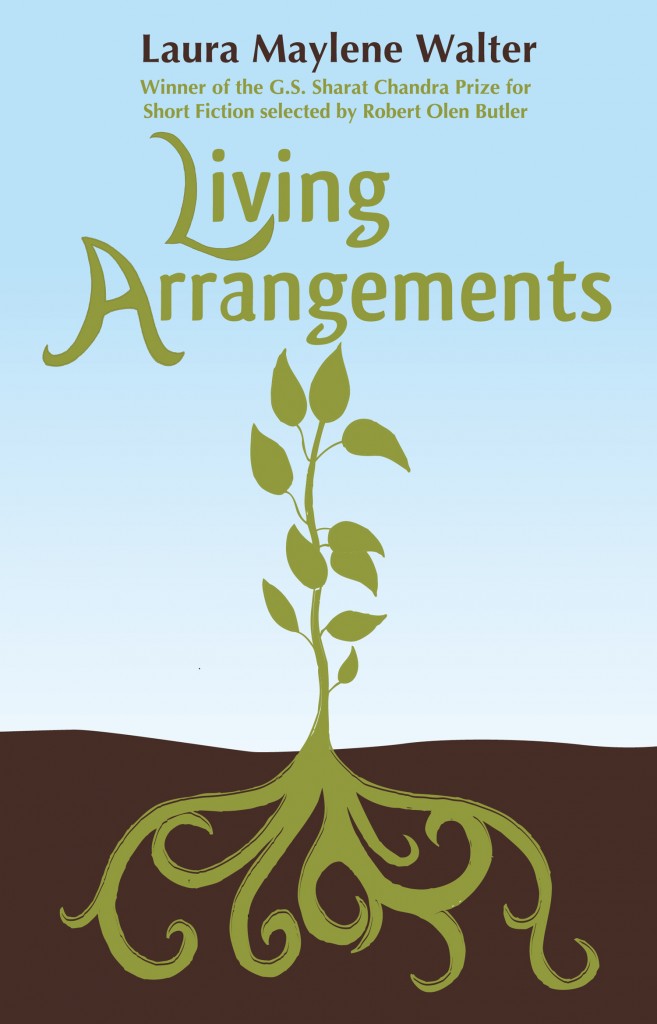

Full Disclosure: I first met Laura Walter when she was a freshman in high school and I was a senior. We worked on the school’s literary magazine—the unfortunately titled Whispering Minds—together, and I was close friends with her brother Craig for a number of years. I played poker on the picnic table in their yard and tasted my first jello shot in their kitchen. When their mother died, my parents briefly took in her dog—a mammoth collie with a penchant for flashlights. Over the years I kept hearing such good things about Laura through mutual friends and then Facebook—that she won the Sophie Kerr Prize at Washington College, that she was getting married, and then in 2011 that she was getting her first story collection, Living Arrangements (BkMk), published—and that Robert Olen Butler and Dan Chaon were blurbing her! I was thrilled. And when I read the book, I was enchanted—compelled by the authority of her narrators’ voices and moved to extreme empathy by their stories. Laura and I began talking about her book in February at AWP, but most of this interview was conducted over email this spring.

Laura Walter lives in Lakewood, Ohio. She is a Senior Editor at Penton Business Media, and her stories have been published in the American Literary Review, Inkwell, the Nashville Review, and the Crab Creek Review, among other journals; she blogs at lauramaylenewalter.com. Living Arrangements has been awarded the National Gold 2012 Independent Publisher Book Award (IPPY Award) for Short Story Fiction (tied with Jeff Kass‘s Knuckleheads) and was named a finalist in ForeWord Reviews‘ Book of the Year Awards.

Interview

Anne Stameshkin: It’s been six months since Living Arrangements published. How does it feel to have your book in the world?

Laura Maylene Walter: In a word, I feel grateful. The experience has been both overwhelming (I often feel there are so many things I’ve failed to do—most of them relating to marketing) and underwhelming at the same time. The world doesn’t stop when your first book is published, and your hopes and goals for the future just keep shifting outward. Through it all, I occasionally still feel surprised that Living Arrangements exists at all, and that the stories I wrote years ago with little to no expectations became my first book.

Congratulations on recently winning an IPPY! The manuscript for Living Arrangements was also awarded the G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction. Can you tell us what winning each was like?

I was busy tasting olive oil while on vacation in California when I got the call that I’d won BkMk Press’s G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize. To say I was in shock is an understatement. Being hundreds of miles from home when I received the news didn’t help make it feel any more real, and for a few days I was thoroughly convinced there had been a mix-up and they’d called the wrong person.

Winning an IPPY was another good surprise—but this time I only felt proud of my book. Being a writer often involves feeling insecure and inadequate part of the time and confident the rest of the time. Winning prizes doesn’t change that constant shift between uncertainty and confidence, at least not for me.

What are some advantages of working with a small independent press like BkMk?

I can pick up the phone and almost always reach my editor instantly. In the weeks leading up to publication, I probably drove him a little crazy with all my phone calls, but he was patient and gracious with my anxieties and questions. That kind of personal attention is priceless. I also gave a lot of input on the cover design, and my opinions were always considered and respected. In short, I felt everyone at the press had my best interests at heart, wanted to put out a great book, and wanted me to be happy. That’s pretty amazing.

You’ve been doing some fun things recently to promote your book. Can you talk about some of them? How would you describe your approach to publicity?

If I’m going to self promote, I figure I might as well have a little fun in the process and not take myself too seriously.

I recently gave a presentation at my local library and, instead of a regular reading and Q&A, I decided to do something different. I love going to readings, but some of the best literary events I’ve attended have featured the writer(s) simply talking and sharing stories and experiences. So I created a PowerPoint presentation full of pictures from my past—everything from old diary entries to horrendous childhood artwork to awkward high school photos and embarrassing newspaper clippings—and used those images to help tell the story of my development as a writer, including all the letdowns and disappointment I experienced along the way.

In general, my approach to publicity seems to be rooted in humiliation. As someone who shuts down inside whenever I come across advice on how to “develop your brand” and “market yourself,” I’ve always been a little reluctant on the whole publicity front. Nonetheless, I suppose I have built my own “brand” around owning up to my rejection and disappointments. I’ve written articles and blog posts about my writing failures and have gained a sort of strength from admitting how often I’ve fallen on my face and how far I still have to go in my writing career.

Rejection and humiliation and hope: I think that about sums up my approach to marketing and publicity. Well, that and cats. You can never go wrong with cats.

So true! Let’s talk about the book itself. I was especially drawn in by the title story, which is also the collection’s first, and its take on the shifting ground of the narrator’s “home.” Where did the germ of this story come from? And what role does it play in the collection? Do you feel it ties the stories together?

The essence of that story is how I feel every time I visit my hometown of Lancaster, PA. It’s that longing to go home again even after you no longer can, or after that home no longer exists. It’s a theme that I plan to explore more deeply in the future, and one that the other characters in Living Arrangements struggle with, too.

I see that story as an umbrella for the rest of the stories to come. When I first compiled my collection, I instinctively put the title story first, but then doubted myself after the collection won the prize. I considered moving the title story to the end, or perhaps closer to the middle of the collection, but I discussed it with my editor and we decided to keep it in the beginning. My instinct seemed right—this story of a woman reflecting on all the places she has lived and how impossible it is to truly go back seemed appropriate foreshadowing for what many of the other characters face in the book.

How do you go about titling your stories? What do you think makes—or doesn’t make—a good title?

This is a wonderful but difficult question, because titles either come to me like magic or I struggle with them greatly. The titles for stories like “Living Arrangements,” “How to Speak Czech,” and “To Elizabeth Bishop, with Love” came easily and almost instantly. Other stories have been titled multiple times. “Return to Stillbrook Farm” originally had a very different title that I loved, but it ended up misleading readers in a big way, so I had to change it. For years, the story “A System Based on Counting” went through a long string of titles, and to this day I don’t understand why the perfect title for that story has eluded me.

We share the same hometown, and I loved that sense of Lancaster, PA, that comes through in some of these stories. For any writers passing through the area, what would you recommend they do or see? I always wax rhapsodic about the tomatoes…but admittedly, that’s a seasonal thing.

What I wish I had more time to do whenever I return to Lancaster, and what I’d recommend to others, is simply driving through the farmland and Amish country. I’d also recommend seeing a show at the Fulton Opera House, walking around downtown Lancaster to explore the shops and museums, going to Root’s Market in the summer, spending an afternoon at Long’s Park, walking over the Columbia-Wrightsville bridge that spans the Susquehanna, and making a visit to the Watch and Clock Museum in Columbia.

Those are great suggestions. I’ve still never been to the Watch and Clock Museum…

You also write beautifully about mother-daughter and sibling relationships in your fiction. I hope it’s not too personal a question, but I wondered how much your mother—your relationship with her and her death—inspires your stories. The wide variety of mothers in your stories is a testament to the fact that they are not simply autobiographical, but is there a piece of your mother in all of those mothers?

My mother continues to influence my writing career even today, eleven years after her death. As an aspiring writer herself, she grasped the complexities of the writing life, the publishing world, and what it takes to be a writer. She championed all my young writing attempts as any mother would, but she also understood my dreams and shared many of them. We talked about writing often and I knew she had high hopes for me. Now, whenever something positive happens in my writing career, I think of her and what she would say or how she would react.

Her death deeply influenced my work. Themes of grief and of dying, or of distant or toxic mothers appeared in my writing after she died and sometimes continue to persist today. While my own relationship with my mother could not be described as distant or difficult—we had a close relationship, and I was devastated when she died—my writing, at times, continues to explore what it’s like to go through life without a mother.

And yes, a piece of my mother appears in some of my fictional mothers, but I say that while feeling fiercely protective of her and of my relationship with her.

Do your living relatives and friends see themselves or her in your fiction, and have you had any confrontations or discussions about it?

One of my brothers told me that at times, reading my book was like “reading his childhood.” Family members are much more likely to try to read autobiography into your fiction, so on one hand I wonder if he was trying a little too hard to connect the dots. On the other hand, I take this as a compliment that the details and flavors I included in the book resonated with someone who could recognize the genesis of at least some of those details.

Someone else was curious whether I’d actually worked as a lingerie model like Margaret in “Live Model,” which gave me a good laugh.

Do you cringe when writers offer advice like “write as if your parents are dead”? What do you think this saying means?

I’m about to start working on some nonfiction pieces about my mother and our relationship before her death. Would I be focusing on these stories and on this time in my life had she lived? No, and not only because her death is what shaped those months and years into a defining point in my life. I’m also not sure how I’d feel if she could read it.

There is a freedom that comes in writing about someone who is no longer alive, but there is also a responsibility. My mother isn’t here to defend herself. While I’m free to write about her as I see fit, I understand more than ever the importance of being honest and fair to my memories of her.

Some writers are held back by worries of how their families will react to their writing, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. I can’t argue with the “write as if your parents are dead” advice if it helps these writers let go. Of course, that advice mostly embraces the first piece of what I mentioned above—the freedom—but the responsibility remains, whether or not the person has passed.

You write in a wide range of close and distant POVs, using the first-person, second-person, and third-person in your stories. How do you choose what point of view to use? Does your narrator’s voice emerge naturally, or do you think about it or even—as Ishiguro does—“audition” different voices?

The second-person pieces emerged that way naturally. In fact, the voices in those stories came through so strongly that I felt I had no other choice. For some of the other stories, I consciously decided to write in either third or first person. Occasionally I might make a wrong turn in a story and have to go back and change the POV, but usually what I choose from the beginning feels right.

“The Ballad Solemn of Lady Malena” [about a reporter’s obsession and interactions with a teenaged figure skater] is a really daring story, as delicious as it is discomforting…I have to say Humbert Humbert sprang to mind…and I thought you handled the idea of desire beautifully. What inspired this story, and what was it like writing from this narrator’s point of view?

That story began as a twenty-minute story exercise, which I first read about on McSweeney’s. I simply set a timer for twenty minutes and tried to write a story in that short time. What I ended up with was one scene of “The Ballad Solemn of Lady Malena,” when Annabelle takes the ice for her competitive long program while the narrator watches from the stands.

I’ve always had an interest in figure skating, which is why I made Annabelle a skater, but beyond that I did not plan the story at all. Writing from this narrator’s point of view was dark and thrilling and exciting. His voice came very naturally for me, and I have since written a few new stories in a somewhat similar point of view—I call it my “creepy and/or predatory male point of view.” I don’t know what it says about me that this type of voice comes so easily, but there you are.

Who are the writers that made (and make) you think, I want to do this? What is on your nightstand right now?

Who are the writers that made (and make) you think, I want to do this? What is on your nightstand right now?

Alice Munro, Flannery O’Connor, Ann Patchett, and Susan Minot, to name just a few. Right now on my nightstand I have Anne Lamott’s Imperfect Birds, a recent issue of Gulf Coast, and a battered and falling-apart copy of Middlemarch.

Do you have a favorite short story?

I have always loved Alice Munro’s “Boys and Girls.” The images of the fox farm and Flora galloping away have stayed with me ever since I first read the story as a teenager.

And since it’s Short Story Month, I’ll ask what your favorite thing is about short fiction—reading or writing it. Why is short fiction important to you?

When I sit down to write a new story, I love the possibility and the tension inherent in creating characters and an entire world in such a compact way. In some ways, the length limits of a short story actually make me feel liberated. That’s how I feel when I read stories, too—completely willing to dive in and see where this writer will take me in relatively few pages.

Why do you think so many readers say they don’t like reading short stories, and how can we convert them?

We often hear that readers don’t like to be pulled out of a fictional world after a few pages only to have to enter a new one again and again throughout a story collection. But I think short stories can complement our typical reading habits today—at least the habits that come through in our online reading, which usually involves reading something short and then moving on to something else.

I think you’re completely right that short stories seem—at least on paper (er, screen?)—to be a better fit for readers today. I wonder as we make more and more of a transition to reading online and through e-readers, if this might actually help short fiction. I want to believe there are some benefits of what is an inevitable sea change…

I think we’re about due for a short story renaissance!

I agree! So, what are you working on now? What’s next?

I’m working on new short stories, some creative nonfiction pieces, and two novels—one that I’ve been revising for a few years now, and one that is in its infancy, just a little flash I can see from the corner of my eye…