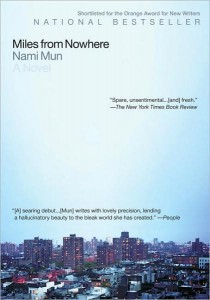

Nami Mun’s debut novel, Miles from Nowhere (Riverhead, 2008), tells the story of Joon, a teenage runaway on the streets of New York. It’s a story of survival on two fronts, as Joon must struggle to sustain not only her physical life but also her moral one: an ability to feel love and pity, and a willingness to accept such gifts from others. Her journey is harrowing, but her resilience lends the novel luminosity even in its darkest moments. Miles from Nowhere reminds the reader that clear-sighted observation–performed honestly and without blinking–can become an act of compassion. The book has rapidly garnered critical recognition; its accolades include selection as one of Booklist’s Top 10 First Novels and inclusion in the Orange Prize for New Writers shortlist. And Nami herself recently received a 2009 Whiting Award.

Nami Mun’s debut novel, Miles from Nowhere (Riverhead, 2008), tells the story of Joon, a teenage runaway on the streets of New York. It’s a story of survival on two fronts, as Joon must struggle to sustain not only her physical life but also her moral one: an ability to feel love and pity, and a willingness to accept such gifts from others. Her journey is harrowing, but her resilience lends the novel luminosity even in its darkest moments. Miles from Nowhere reminds the reader that clear-sighted observation–performed honestly and without blinking–can become an act of compassion. The book has rapidly garnered critical recognition; its accolades include selection as one of Booklist’s Top 10 First Novels and inclusion in the Orange Prize for New Writers shortlist. And Nami herself recently received a 2009 Whiting Award.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Nami grew up there and in the Bronx. She has worked as an Avon lady, a street vendor, a photojournalist, a waitress, an activities coordinator for a nursing home, and a criminal defense investigator. After earning a GED, she went on to get a BA in English from UC Berkeley and an MFA from the University of Michigan. Her stories, several of which appear as chapters in Miles from Nowhere, have appeared or are forthcoming in Granta, Iowa Review, Evergreen Review, Witness, Bat City Review, Tin House, and elsewhere. She currently lives in Chicago and teaches at Columbia College.

Nami and I were classmates at the University of Michigan, where I had the pleasure not only of reading several sections of Miles from Nowhere in workshop, but also of sitting down in Nami’s living room every so often for a cost-effective and stylish haircut. We live in different parts of the country these days, so the following conversation took place over a series of e-mails.

Interview

GREG SCHUTZ: Miles from Nowhere is narrated by Joon, a teenaged Korean girl, a runaway. Meanwhile, you’re Korean-American, and your dust-jacket bio reveals that you’ve worked as an Avon lady and a dance hostess—jobs that Joon herself holds at certain points in the novel. Customer reviews on sites like Amazon and Goodreads, show some speculation about this book being autobiographical. I know this is something that’s come up for you in other interviews as well, so maybe we should begin by setting the record straight: what is the relationship between Joon’s experiences in Miles from Nowhere and your own life?

NAMI MUN: Considering that I also left home for good at an early age, and that I’ve held some of the jobs Joon does in the book, I think it’s very fair for readers to wonder if the book is autobiographical. Emotionally speaking, the book definitely expresses some of the feelings I have felt in my life, but the actual scenes, dialogue, events, etc. portrayed in the book are very much fiction. To put it in numbers, 99% of Miles from Nowhere is pure fabrication. The remaining one percent represents what I think of as kernels of real life that provided the spark for that 99%.

Of course, many writers use real life or real emotions as starting points. Bruno Schulz comes to mind. As does Kafka. If you read Kafka’s journals and letters, you can see how his strained relationship with his father gets played out in his dreams, and then later on in his fiction. Hemingway is also a good example because he often chose not to write about the actual events of his life, but used the knowledge of them to strengthen his story. Omission is a big part of my fiction writing process. I keep real-life events in a basement-reserve of sorts and hope that their fumes will rise above the floorboards and infuse my narrative.

Of course, many writers use real life or real emotions as starting points. Bruno Schulz comes to mind. As does Kafka. If you read Kafka’s journals and letters, you can see how his strained relationship with his father gets played out in his dreams, and then later on in his fiction. Hemingway is also a good example because he often chose not to write about the actual events of his life, but used the knowledge of them to strengthen his story. Omission is a big part of my fiction writing process. I keep real-life events in a basement-reserve of sorts and hope that their fumes will rise above the floorboards and infuse my narrative.

What do you make of the urge to read fiction as if it were memoir?

I think readers have a tendency to read fiction as memoir because they understand that writing doesn’t occur in a vacuum—that a writer’s imagination often begins in real life and real experiences.

So, why did you choose to write fiction instead of a memoir?

Fiction is my default writing mode. Whenever I witness something odd on the streets or hear intriguing dialogue on the trains, my first impulse is to drop these things into my fiction bank. I don’t have a memoir bank. Fiction, to me, is running through the woods rather than running on a treadmill. It’s freedom to make up characters, setting, situations, etc.—and through this freedom I feel better equipped to express and explore my ideas. Writing about “true” events feels constricting. My hours on the planet are already filled with so many constraints, why add one more? And in case you haven’t guessed it already, I also don’t like following cooking recipes; I hate reading instructional manuals; and my ideal meal is something that contains numerous varieties and options (also known as Korean food). I also prefer writing about things without writing about them directly. Finally, I am also somewhat of a private person, which means I need the veil fiction provides in order to unveil deeper truths about what I’m trying to express.

Why (and when) did you begin writing, and what did your early efforts look like?

My early efforts looked like a clown—a cheap, drunk, whorish clown with smeared makeup, who drove around the country in his banged-up clown car. The emotions relayed were garish and obvious, the writing was strained, and my story ideas meandered all over the place—one day I was writing detective noir, another day a Korean-gothic tale about a girl being tortured by everyone in her hometown (think Blair Witch meets “The Lottery”). And still another day, a magical-realism story about a woman suffering from Sjögren’s syndrome, also known as dried-up tear ducts. But with every single horrific page, I was learning something new—the most important being how to detect an ill-fated story.

One of the things that impresses me most about Miles from Nowhere is the voice of its narrator, Joon. She’s capable of a deadpan accuracy that verges on reportage, but this is a deadpan that sometimes rises to moments of startling, poetic clarity: Joon is a great noticer of details. How did you find her voice?

I test drove numerous voices and characters before I found Joon. But one sentence into Joon’s story, I knew I was onto something; it was that immediate. To me, Joon sounds both frightened and curious, intelligent and naïve, strong and vulnerable. And funny. She also displays stoicism—a quality I admire in her but one that ultimately signifies her repressed emotions. These emotions are there inside, gurgling in her throat. And her deadpan, reportorial voice is a way for her to temper these internal struggles so they don’t bubble to the surface. But then, sometimes, the world is too unbearable for her, and that’s when her voice cracks. That’s when she is forced to see her surroundings with a certain poetic beauty. She needs to see the beautiful, almost as much as the reader needs for her to see it. In the final image of “Club Orchid,” Joon needs to see that 99-cent store. She needs to see those crayon colors, those bottles and boxes of soaps, the shiny floor, and, more importantly, that unbelievable light. No one saved her that night, so she finds a way to save herself by creating light from dark, if only so she can last another day.

What was the earliest impetus for Miles from Nowhere? Did you begin by writing a single short story, or did you know from the beginning that there was an entire book here?

The first story I wrote for the book was “Club Orchid.” In that story, Joon is both vulnerable and strong, and I suppose I liked the tension this dichotomy created on the page, especially when she tries to describe the very adult setting and situations. I went on to write several more stories about her, and maybe a year or two later I noticed how all of the stories revolved around Joon trying to make money to survive. (For example, she works as a dance hostess in one story, sells Avon in another, sells newspaper on subways, etc.) That’s when I realized that these stories, while self-contained, could also be cogs working toward a larger narrative arc.

I also made a crucial decision right then—to keep the episodic structure, primarily because I felt it gave a truer, more visceral reflection of Joon’s fractured mindset.

How long did it take you to write Miles from Nowhere?

It took eight years. During those years I worked a total of six different jobs and earned my MFA. My life was in flux but the book remained my constant. I wrote before work, after work, during lunch, and if possible, during work. I wrote on weekends and holidays. Luckily, my partner of ten years (Augustus Rose) is also a writer, so writing during vacations was never frowned upon. I wrote during vacations.

You must have encountered moments of self-doubt along the way. How did you overcome them?

I am a person who is both plagued with and fueled by self-doubt. This might explain why the book took so long to complete. But my self-doubt was also the force behind the ridiculous number of revisions each chapter went through, which in the end gave me a certain confidence about what I had written. I think the trick is to not “overcome” self-doubt but to learn how to ride it. .

Miles from Nowhere is set in New York (mostly the Bronx) during the 1980s. What influenced your choice of milieu? Was it a challenge for you as a writer, having not only to capture in prose an iconic city about which so much has already been written, but also to capture that city as it was during a particular decade?

Generally speaking, setting is always a challenge—I try to keep it in the background and yet let it breathe and flex its muscles throughout the story. Many stories/novels do this successfully—Paul Bowles’ “How Many Midnights” comes to mind, as does Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland. Both authors treat New York as an entity that dramatically or subtly carries the weight of character wants and fears. And in this way, the setting works as a guide, communicating to the reader when the characters cannot.

For these reasons (and many more) New York was the perfect backdrop to reflect the mercurial nature of Joon’s inner and outer life. And while writing the book, I tried not to think of New York as belonging to Woody Allen, Dorothy Parker, Dawn Powell, Paul Auster, E.L. Doctorow, Hubert Selby, Jr., Richard Price (I could go on)—but as the city I grew up in, took shelter in, went to the movies in, had my first kiss in. And I focused on Joon’s New York, how small and dark and cold it would feel to her, especially in the 1980s, the decade of self-serving.

photo by Tony the Misfit (flickr cc)

photo by mk B (flickr cc)

You surround Joon with something like an ensemble cast—these characters who cross her path for a few chapters or a few pages or even just a few lines. I still remember (without going into too much detail here) the man who tells Joon the story about falling from a tree, or the old man carrying the dog in the grocery basket. Where do minor characters like these come from? Do you conceive of them in advance, and then find ways to work them into your narrative, or is it the other way around—does the sensed need for a particular sort of encounter determine the kind of person you have Joon meet?

I don’t know where they come from, but I hope they keep coming. How they work within a narrative differs with every story, and trying to talk about them feels like trying to describe magic or spirituality. What I do know is that they are minor folks who play a major role. They might facilitate an important change within a character, or they might provide a final push toward the all-important climax. And even if I conceive of them in advance, they only make their way onto the page if and when the story needs them to. The minute I try to “work them into a narrative,” I can feel the strain, and the story suffers.

I’m thinking about this passage on characterization from James Wood’s How Fiction Works:

[Ford Madox] Ford and [Joseph] Conrad loved a sentence from a Maupassant story, “La Reine Hortense”: “He was a gentleman with red whiskers who always went first through a doorway.” Ford comments: “That gentleman is so sufficiently got in that you need no more of him to understand how he will act. He has been ‘got in’ and can get to work at once.

Your prose possesses this same facility for quickly “getting in” your characters. (For example, the medical assistant at the abortion clinic whose “voice was too loud for the size of the room,” and who shortly thereafter “clicked her pen into action” to record Joon’s responses to her questions.) How do you find these details—ones that can immediately vivify a minor character?

Maupassant’s detail is very telling of M. Cimme’s pitiless and haughty attitude toward the people around him, which foreshadows and perhaps partially explains his insensitivity toward the dying woman later in the story. In a short story (especially one as short as “La Reine Hortense”) every detail must be specific and yet all-encompassing. With the details I wrote for the medical assistant, the goal was to describe her and Joon’s state of mind simultaneously. Hopefully the reader senses that the Medical Assistant is a taskmaster, a person of confidence, a person in complete control of her actions. Basically, she is the opposite of Joon, who in that scene is floating in a haze of heroin. So it seems right to have Joon notice and be annoyed by the sounds, as well as any fast movements, such as the clicking of the pen. I think once I truly entered Joon’s perspective, insignificant details fell by the wayside.

Much has been made of the criticism that MFA workshops somehow flatten the fiction of their participants, forcing stories and novels into predictable, “safe” forms. But a book like Miles from Nowhere, by being both excellent and daring, seems to me the perfect counterexample. What effect did your time in the M.F.A. program on the University of Michigan have on Miles from Nowhere? Is there truth to the concept of the “workshop story” or of “MFA fiction”?

The University of Michigan’s MFA program gave me everything a writer could want: time and money to work on my manuscript; brilliant mentors (Peter Ho Davies, Eileen Pollack, and Michael Byers, to name a few) who guided me toward the end of the book; crucial teaching experience; and an extremely keen group of workshop mates who came to class with an open mind as well as a critical eye. During those two years of workshops, I never saw a single story that was “flat,” “predictable,” or “safe.” Maybe I got lucky. Or maybe my mates were mature enough as writers that nothing in the universe could have flattened their work. That was certainly the case with Uwem [Akpan]’s stories about child trafficking in Africa (Say You’re One of Them), Preeta [Samarasan]’s writing about family and politics (Evening is the Whole Day), and Michael [Shilling]’s novel, Rock Bottom, about a band on the last day of its tour. All of these novels are so vastly different from one another, but they are all powerful in voice, and in story. So when people talk about flat “workshop” stories, I thank God that I’ve never personally experienced this phenomenon.

But to answer your question about whether workshops churn out flat writing, I have to say that flat writing makes flat stories, and no one or thing could be blamed except the writer.

I know, both from having participated in MFA workshops with you and from reading literary journals, that some chapters of Miles from Nowhere had their geneses as short stories. So, as an avid reader and writer of short stories, I hoped we could talk about the form for a moment. What was it that initially drew you to the short story as a vehicle for your material?

I love the speed the form allows, as well as the depth. I love how one day, or one moment, can speak for a lifetime the way it does in the best of stories, like “A&P” and “Bullet in the Brain.” And how the form also allows a writer to cover years and years of a character’s life within a mere few pages, as in “Grippes and Poche” by Gallant, “Miserere” by Stone, or “The Store” by Edward P. Jones. I also love the language, how absolutely precise it needs to be, how no word is wasted. And I love how the form is conducive to multiple revisions, my favorite part of writing.

Speaking of revisions, how do you know when a story is finished?

I think it’s akin to falling in love; you know it when you know it. Or maybe it’s like recognizing pornography?

You won’t want to hear me say this, but I remember that, while you were studying here at Michigan, your work ethic was near-legendary. You were willing (or so the legend goes) to sit at your desk for eight hours straight, working on a single sentence—getting the words right, the voice, the rhythm. Any truth to these rumors? What does your day-to-day writing process look like?

Well, I’m not sure if this is something I’m proud of, but yes, I do often write for eight to ten hours a day when I’m working on a piece. But that only proves that I don’t exercise, and that I don’t have much of a social life. I don’t know about working on single sentence that entire time—that really does sound apocryphal—but yes, I sometimes have only a paragraph to show for my hours of work. Again, it’s not something I’m necessarily proud of because it only proves how slow my brain works.

Would you say that this kind of tenacity is necessary for a writer of literary fiction (he asked leadingly)?

Many folks tend to romanticize the life of the writer. I think that’s because they see us after we’ve written the book or the story. They don’t see us sitting in at our desk for weeks, months, years on end—losing weight, losing muscle mass, feeling depressed, not showering. (This is why they have reality TV shows about dancers, chefs, and models, and never about writers.) Yes, tenacity is a requirement, for all writers and not just writers of literary fiction. Tenacity, thick skin, the ability to sit still and focus—these are more than necessary.

Any other advice for young writers, or for anyone coming to the craft of fiction?

Write about things that actually matter to you. If your story is founded on some “clever” premise or “quirky” characters who experience “idiosyncratic” situations, write until you find in your story something that matters to you. Aimee Bender, George Saunders, and Donald Barthelme (just to name a few) are masters at combining ingenuity with empathy, cleverness with compassion. If you don’t feel anything for your story, no one else will.

Now that Miles from Nowhere is on bookstore shelves, where do you go from here? What are you working on these days?

Since my criminal defense investigator days, I’ve always been interested in crime—not so much the “whodunnit” aspect, but more the philosophical stance of defining a person based on one single action. So I’m working on a novel about crime. I’m also writing a story about a boxer.

Further Resources

– In this video (via Amazon’s Omnivoracious), Nami talks at BookExpo about Miles from Nowhere.

– Find more interviews (print and radio) with Nami…in the Chicagoist, on San Francisco Metblogs, in the Independent, on K-Popped, on APA Compass Radio, on Minnesota Public Radio, and on Chicago Public Radio (interviewed by Eight Forty-Eight‘s book critic Donna Seaman).

– Join the Miles from Nowhere Facebook group.

– Connecticut-based writers, Nami is giving a reading next Thursday, November 19 at Trinity College in Hartford, CT. Part of the A.K. Smith Reading Series, it will be held in the Reese Room in Smith House at 4:30 PM.

– If you’re shopping for a copy of Miles from Nowhere, visit your local independent bookstore.