Fictional works teach us how to read them, and in the case of Carrie Messenger’s short stories in her Brighthorse Prize-winning collection, In the Amber Chamber, each story introduces its own terrible and thrilling logic, one that the reader follows exactingly to the conclusion. The logics of these stories are on one hand familiar—Messenger’s work draws from fairy tales, speculative and science fiction, as well as Eastern European history—but conventions and expectations meld, disintegrate, and transform. What results are new, uncanny, and unsettling literary worlds, where magic is concurrent with—and perhaps a result of—corruption and exploitation. Take, for example, the summary at the beginning of “Reports on the Capra Family in the Village of C,” the Village of C a recurring setting in the collection:

Another chronicle of our intrepid comrade Grimm in his investigation into the rumors of the famine years, and just how many cannibals live amongst us in C to this day, and how we should be kind to them because it’s in their nature. And the potential uses of this instructive tale for relationships between the classes of goat and wolf within our new glorious society, as the wolf now truly lies down with the goat. (See the reading primers for second and fourth forms and their three-toned illustrations of slightly edited but still gleefully murderous versions of the tale.)

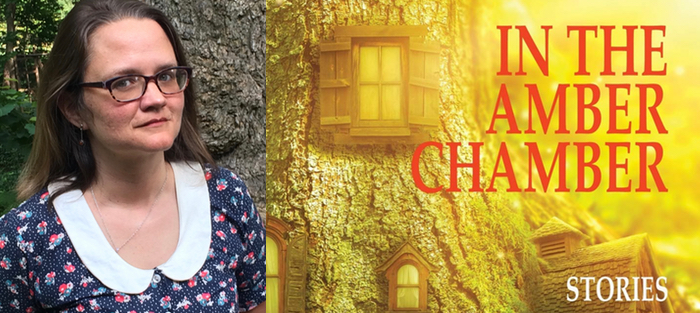

“The famine years” refer to the Moldovan Famine of 1947, which, as Carrie addresses in this interview, became an obsession for her. She graduated from Yale before she served as a Peace Corps Volunteer for two years in Straseni, Moldova, which has had a profound influence on her work as an MFA and PhD student, writer, translator, and teacher of literature and film. She received her MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, then returned to Moldova for a year on Fulbright, and proceeded to receive a PhD in Creative Writing from University of Illinois – Chicago. Today, she is an associate professor of English at Shepard University in West Virginia, where she lives with her family.

I first met Carrie nearly two decades ago when my band was on a Midwest tour and she came to our show at Gabe’s Oasis in Iowa City, just as she was finishing her MFA. Her dad, an English professor, was my undergrad Honors Fellow, and he suggested to Carrie that she meet me at the show. She kindly invited my band to crash in her living room that night—the drummer and I noted a videocassette of The Third Man next to the VCR. Carrie and I corresponded while she was on Fulbright in Moldova, and when she moved back to Chicago we regularly met for coffee and dinner, for theater, literary events, and concerts. Writing has always has always been one of many topics for us, as we’ve introduced each other to music, writers, and food, and spent time together with our families. So it was a new pleasure to spend this time via email with Carrie, focused exclusively on her collection and writing life.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: I’ve always looked forward to reading your stories as they’ve been published, but to read them in ensemble is another experience—sometimes otherworldly, at moments overwhelming, but always transfixing. You are the kind of writer who seems to cast a spell over a narrative. But I’m going to begin with a couple of mundane questions. You have been writing and publishing the stories included in this collection over the course of two decades. At what point did you decide this was a collection, and how did you determine the sequence?

Carrie Messenger: At first, I did think my collection was going to simply be the stories I had published. But when I looked at what I had, there were some clear themes. At the same time, I’d started to read about the Moldovan famine of 1947 and had become obsessed with it. I wanted to write about it, but realistic historical fiction seemed impossibly bleak, and I had to find a different way to tell the story. Those new stories helped me figure out which stories belonged in this collection, and which stories were orphans.

It sounds like you wrote some of these stories expressly for the collection, then.

I did write some stories specifically for the collection. Once I had a science fiction story with “The Inn of the Former Rural Farmworkers,” I wanted to pair it with “Underground Pastry.” Most of the stories that were specifically about food and famine I wrote while I was at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, which gave me some very strange conversations at lunch and dinner. Some people wanted to talk to me. Some people moved further down the bench.

Yes, about those stories: Famine leads inevitably to cannibalism, sexual exploitation of adolescent girls, parents abandoning children, and murder. Grotesque, but also reassuring for the reader—you don’t shy away from the horror of these historically rooted situations. Often, you establish a story’s logic within the first few lines. You attribute the five fairy tales set in the eponymous “Village of C” to Comrade Grimm, and we get the setting and stakes in the title and a prefatory note. Other stories in a social realist vein—such as “In the Pines” and “The General and His Wife Attend the Graduation of Their Grandson”—open with whispered gossip or supposition. How did these conventions emerge and evolve in your work?

I kind of think about fairy tales as doing the work of gossip. I’ve always been interested in what people know but nobody talks about. I was always trying to listen to whispered conversations. In the story “In the Pines,” with its multiple first person narrators, or the general narrating his own story when earlier we have heard from his daughter, I was thinking of first person as a kind of gossip. Fairy tales are almost always told in third person, but almost from a first-person plural. (I originally used first-person plural in “How the Romanians Ruined Christmas.”)

I kind of think about fairy tales as doing the work of gossip. I’ve always been interested in what people know but nobody talks about. I was always trying to listen to whispered conversations. In the story “In the Pines,” with its multiple first person narrators, or the general narrating his own story when earlier we have heard from his daughter, I was thinking of first person as a kind of gossip. Fairy tales are almost always told in third person, but almost from a first-person plural. (I originally used first-person plural in “How the Romanians Ruined Christmas.”)

Open secrets—as you put it, “what people know but nobody talks about”—are also central to many of your narratives. This puts your collection in dialogue with the #MeToo movement, which exploded right around the time In the Amber Chamber won the Brighthorse Prize. How do you balance the literary and aesthetic with the social and political in your work?

When I was a Peace Corps Volunteer, Alice Munro’s Open Secrets had just come out, and I read it obsessively. “The Albanian Virgin” particularly made me think about ways you can get lost in somebody else’s culture and life. I’ve never been good at keeping secrets. When I was at Iowa, the Workshop people thought I was too interested in the political, and the English department people thought I was hopelessly invested in aesthetics. I liked feeling like an outsider in both groups.

You shift geography and social concerns over the course of the collection—we start in Romania, Moldova, and an Eastern Europe of fairy tales before shifting to Chicago and its north surburbs. Was this part of the organizing principle of the collection?

Yes, absolutely. As I put the collection together, I was thinking about my own personal geographies. Chicago feels like a very Eastern European place to me, for the weather if nothing else. I also didn’t want the collection to feel like fairy tales, or history, only happen somewhere else, to other people. The book I am working on right now is a novel about Chicago in the late 1960s, and the stories of those revolutionary years feel like dark fairy tales too, from the murder of Fred Hampton to the Days of Rage and the rise of the first feminist group Westside.

Have your aims for this novel—and maybe your writing overall—shifted, or changed in urgency, given the turn toward state abortion bans and other legislation regulating women’s health and autonomy? What do you see as the fiction writer’s role—and maybe your role in particular, given the subjects you address in your work—since Trump became president?

I would really like it if this novel wasn’t so timely. When I started it, police brutality was very much in the news, and the more I work in the book, the more it feels like the past isn’t past. I first started reading about Jane and Chicago feminist groups when I had a summer job at Northwestern Library’s Special Collections. During my time in Eastern Europe, I was interested in Romania and Moldova’s very different abortion histories. Abortions were readily available in the Soviet Union, but unfortunately were often used instead of birth control. Romania was unusual for Eastern European communist countries in that Ceausescu banned abortions. Birth control was also limited. My story “In the Pines” covers some of this material. (The amazing Cristian Mungiu movie 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is about the choices people had to make in those years.) When I was first interested in Jane, I was interested in seeing how American history matched up with Romanian history. History never stops. It keeps making more, and I think writers and historians need to document the open secrets.

The number of MFA programs in the US has more than doubled over the past ten years, and between social media and noncredit institutions and organizations that offer creative writing classes, there is a broad range of options available for people who want to work on their writing outside the MFA. Yet great storytellers existed in the world long before MFA programs. So when a student comes to you and says they would like to pursue creative writing more seriously, what advice do you give them?

I teach at a public liberal arts college in West Virginia, and most of my students are from West Virginia. I am nervous about them taking on debt to study creative writing, but if they can get into a funded program, that is a wonderful opportunity of time to work on their own stuff. But so many amazing writers never got or needed an MFA, so if there are other ways to find time to work, that is something I also encourage. I love teaching literature and film as well as creative writing, so the PhD is useful for me, but that isn’t something that everybody needs by any means.

You’ve also translated quite a bit from the Romanian, both prose and poetry. Has that work influenced your fiction? How so?

You’ve also translated quite a bit from the Romanian, both prose and poetry. Has that work influenced your fiction? How so?

Translating Romanian has given me the chance to inhabit the space of Romanian literature and read it intensely in order to translate. I’ve been lucky enough to translate writers whose work has blown me away as a reader, and I want to figure out how to make that experience happen for English readers. The work of the extraordinary novelist Gabriela Adamesteanu has influenced me greatly. Her fiction is hyperreal so that it becomes surreal, and it feels like living in Romania.

Translation fascinates me as an intellectual and cultural exercise. I was drawn to reading works in translation as early as I was drawn to fairy tales. There is a playfulness and a wry bitterness to Romanian literature that feels distinct. I am interested in other Eastern European literatures as well—I just taught a class in Russian Soviet and contemporary literature, where we read Babel, Bulgakov, Petrushevskaya, and Ulitskaya—but Romanian is the language I can translate because I was lucky enough to learn it as a Peace Corps Volunteer. I desperately wish I knew Russian, too.

You have so many possible avenues for future projects. But you mentioned the novel-in-progress, about Chicago in the late 1960s, so let’s conclude with that: for you, how is working on a novel different from working on a story collection?

I love that short stories are tales—that you need to hold somebody’s attention the way you would if you were talking to them. With novels, it’s a Scheherazade situation, and you’re trying to get them to come back and stay. I’m addicted to long television shows that just keep churning out narrative; I may be one of the last Americans who still watches a day time soap. A novel feels like a soap opera, in a good way.