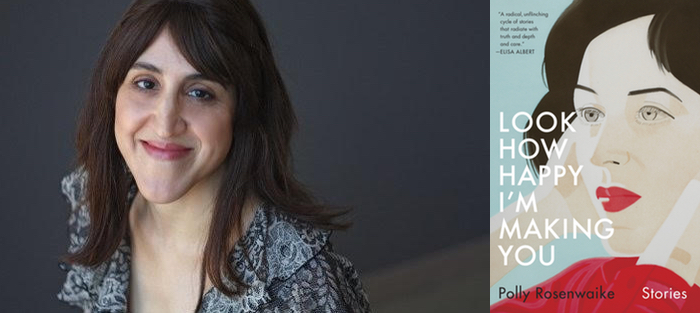

The stories in Look How Happy I’m Making You (Doubleday, 2019), Polly Rosenwaike’s marvelous debut collection, take human agency seriously while acknowledging how much is beyond our control. Her characters don’t always know what they want when it comes to children. When they do, they may not get it; if they get it, it will not be exactly what they hoped. These are stories that trade in the full range of human emotion, including some of the scarier ones. In “Ten Warning Signs of Postpartum Depression,” for example, the narrator imagines a long list of ways she might harm or kill her newborn: “Kitchen knife, pruning saw, refrigerator, oven. Bathtub, washing machine, the trunk of the car….Over and over again, you save him from yourself.”

I first met Polly through a writing group in which I had the pleasure of reading earlier versions of some of the stories in her book. I and other group members have long admired a particular tone in Polly’s work that I think of as her trademark: ironic but not satirical, a little dark but never bleak. Take the book’s title. One could imagine someone saying that sentence with delight to a partner or friend whom one had in fact made happy (“Hurray! Look how happy I’m making you”), but knowing Polly, I suspected it might be a plea from a mother to a child (“See, I’m a good mother—look how happy I’m making you”). In the story it appears in, “Grow Your Eyelashes,” it turns out to be a childless woman’s sardonic response to her mother’s claim that having children would bring her joy. The book abounds in such seemingly everyday moments that reveal the complex dynamics of human relationships.

The stories in this collection have appeared in venues such as The O. Henry Prize Stories, Indiana Review, Colorado Review, and Glimmer Train. Polly’s reviews and essays have also appeared in the New York Times Book Review, The Millions, and The Brooklyn Rail.

Currently, she serves as fiction editor for Michigan Quarterly Review and works as a freelance editor. She lives in Ann Arbor with the poet Cody Walker and their two daughters. We spoke via email.

Interview:

Danielle LaVaque-Manty: The characters in Look How Happy I’m Making You all contend with the prospects of pregnancy and motherhood in some way, whether they want to be mothers or not. At what point did you decide to write a collection of stories on these themes? Did you find yourself with a handful of related stories and decide to keep going, or did you set out with a unified project in mind early on?

Polly Rosenwaike: Before I had my first baby in 2010, I’d written three of the stories in the book: “Field Notes,” about a biologist who decides to have an abortion; “White Carnations,” about a group of women whose mothers have died getting together on Mother’s Day; and “Grow Your Eyelashes,” about a couple trying to conceive. I had it in mind to write a story collection (I’d had it in mind for a long time), but the theme was basically going to be “things the author felt like writing about.” After my daughter was born, I was too stupefied to return to fiction for a while. When I did, what I felt like writing about was pregnancy and new motherhood. Once the collection became more specifically focused on what I wanted to express about these experiences through fiction, it became easier to commission myself to keep forging ahead.

How did you decide it was time to seek an agent for the collection? And how did you decide which of your stories to include and which to leave out?

When I was in my early twenties, I spent a year as an assistant to a literary agent in New York. I sat in a tiny cubicle with piles of manuscripts all around me, and so I acquired some knowledge of and a good deal of respect for the process. Later, working on my own manuscript, I didn’t want to pitch it into a giant pile until I thought I’d done the best I could do. (Of course, submissions are almost all electronic now, but that image of an agent or agent’s assistant drowning in paper persists.) After over a decade of work on these stories, I cast my queries out to a bunch of agents who represented writers I admired, or who otherwise seemed like possible fits for me. My hope was that one of them—and then an editor at a publishing house—would tell me I could do even better and would support me in that effort. I was lucky enough to find my dream team, almost two decades after my brief, paper-slogged, publishing stint.

When I was in my early twenties, I spent a year as an assistant to a literary agent in New York. I sat in a tiny cubicle with piles of manuscripts all around me, and so I acquired some knowledge of and a good deal of respect for the process. Later, working on my own manuscript, I didn’t want to pitch it into a giant pile until I thought I’d done the best I could do. (Of course, submissions are almost all electronic now, but that image of an agent or agent’s assistant drowning in paper persists.) After over a decade of work on these stories, I cast my queries out to a bunch of agents who represented writers I admired, or who otherwise seemed like possible fits for me. My hope was that one of them—and then an editor at a publishing house—would tell me I could do even better and would support me in that effort. I was lucky enough to find my dream team, almost two decades after my brief, paper-slogged, publishing stint.

Because of the thematically linked nature of the collection, with its chronological movement through pregnancy and early motherhood, and also because I’m not a writer with tons of stories up her sleeve, there wasn’t much of a selection process. Two stories I’d written drafts of were abandoned along the way: one because, as my partner rightly pointed out, I was trying too hard to be funny; and the other because I couldn’t figure out what the story was about. That second, muddled, story included some things I wanted to depict in the collection—a home birth, a young nanny’s relationship with her infant charge, a new mother’s relationship with her breast pump—but when the overall arc of the story wasn’t coming together, I let it go.

This collection includes not only stories told in first person and third, but also second person and first-person plural. Do you typically know what point of view will suit the story you want to tell when you begin drafting? Is this an analytical decision for you, or do you arrive at it intuitively, or through trial and error?

I can’t think of a time when I’ve changed the point of view I started out with. When I’m writing a story, not much feels fundamental to me, beyond change, but the intuitive sense of point of view may be the one thing I don’t tamper with. I’m sure I’m not alone in saying that reading Lorrie Moore’s first collection, Self-Help, made me really want to write a story in second person. It wasn’t until I conceived of “Ten Warning Signs of Postpartum Depression,” though, that I think my stab at it made sense. The story takes the “warning signs” from an informational site on postpartum depression and uses that frame to develop a particular character’s experience. I relied on second person both to lend an air of generalized pamphlet-speak and to convey the character’s despondent feelings.

In “Welcome to Your Family,” I tried to channel Moore once again, specifically her story “Charades,” from Birds of America, in which she dips into several points of view at a fraught family Christmas gathering. I’m usually pretty monogamous with my perspectives, sticking to first person or to a close, limited third. It was exciting to experiment with dipping into the heads of a cast of characters, related or related-by-marriage, during an infant’s first holiday season. In “Parental Fade,” I enjoyed using the first-person plural. The story mocks the “we” language couples often employ—“all we think this and we like that”—but it also attempts to embody that unified front of parenthood, when the fact of having a baby together makes you realize how bound to each other you are, with all the simultaneous conflict and sweetness that entails.

Have you written any stories from a father’s or would-be father’s point of view? Is that something you avoid, something you might do in the future, or something you’ve done but didn’t feel belonged in this book?

Well, in “Welcome to Your Family,” we do see Jack’s point-of-view as a new father, but we also see the p.o.v. of his wife, mother, mother-in-law, and baby daughter, so I realize he doesn’t get all that much airtime. I’ve almost always been drawn to writing from female perspectives, and that was especially the case with this book’s focus on women’s reproductive lives. I wanted to explore how the uniquely female experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding might impact women who otherwise often try to resist traditional gender roles. Certainly fatherhood is a life-changing experience too, and I’m sympathetic to the particular challenges fathers face. To be honest, though, I find it difficult to represent male characters in fiction. That’s something I need to work on. I’m envisioning a male point-of-view character for a future project, and I hope I can pull it off.

In “Grow Your Eyelashes,” while the narrator and her husband try diligently to conceive, the narrator’s sister becomes pregnant by accident. In “Period, Ellipsis, Full Stop,” Cora miscarries a wanted child. In “The Dissembler’s Guide to Pregnancy,” the narrator succeeds in getting pregnant but not so much in sustaining her relationship with the baby’s father. In “Love Bug, Sweetie Dear, Pumpkin Pie, Etc.,” Serena’s life is upended when her husband, who had embraced childlessness when they first married, decides he wants children after all. I was struck by how many of these stories convey the lack of control we have over our lives through the relationship between the characters’ desires about children and the unreliability of their bodies, their partners, and even their future selves to align with those desires. Is that a theme you intended?

Yes, I find lack of control—over one’s own unreliable body, over what other people do and feel—incredibly vexing. In writing fiction, we’re controlling our characters, driving them into the path of conflict, and this theme you identify is one I often choose, probably because I have such a hard time with it myself. And it’s especially in play, I think, when it comes to pregnancy and motherhood. We get all sorts of messages and advice about how to manage our pregnant bodies, how to mother our children to promote their health and success and socialization and happiness. But there’s so much we don’t have power over. You can’t stop yourself from having a miscarriage. You can’t make the baby sleep when you want her to. You can’t shield your children from so many things they’ll encounter in life. Striking the right balance between doing what you can to guide them and accepting that there’s only so much you can do is one of the great challenges of parenthood.

You’ve experienced giving and getting feedback on fiction through many different roles—as an MFA student, in a writing group, as a creative writing instructor, as a freelance editor, as fiction editor for Michigan Quarterly Review, and as an author with an agent and publisher. What kind of feedback have you found most useful in your own writing process? And what’s your approach to giving feedback to others?

I find all feedback interesting in that I love how an idea that was once inside my head can take on its own independent life on the page as something separate from me. I’m a fan of the classic workshop model where the writer remains silent, head down, taking notes, taking everything in. Hearing our wonderful writing group discuss how my prose is operating is great fun. I don’t know what I’d do without my brilliant partner’s impeccable line editing and unsparing but ultimately encouraging insistence that I keep working at something that isn’t done yet. I’m lucky to have an in-house editing service; no piece of writing leaves my hands without being screened by him.

As for giving feedback to others, I like both the macro and micro levels of considering someone’s writing. If we’re at the level of talking about the big stuff of character development, or argument (in expository prose), or structure, or voice—whether it’s with a student or an editing client or a friend—I try to put aside my inner zealous copyeditor for a while. I was really drawn to Antonya Nelson’s approach in the workshop you and I both took with her, where the group began by taking the time to describe various aspects of a work rather than diving right into critique. To develop an awareness of craft that allows you to see what your writing is doing—I think that’s the most essential thing. If we’re at the level of line edits, I try to be as thorough as possible. No reason not to try to make all of one’s sentences clean and clear and well-punctuated and stylish and evocative, right? Isn’t that the most important skill in life?

What’s next for you as a writer? Do you have a new project in progress?

I’m (gulp) beginning a novel. My very smart teacher Jonathan Dee once said he never describes a work in progress to anyone, lest they respond with a vaguely bored and skeptical “Huh.” I share his fear, but I’m looking forward to seeing where my held-close-to-the-vest ideas take me.