Melanie Rae Thon’s most recent books are the novel The Voice of the River (September 2011) and In This Light: New and Selected Stories (June 2011). She is also the author of the novels Sweet Hearts, Meteors in August, and Iona Moon, and the story collections First, Body and Girls in the Grass. Thon’s work has been included in Best American Short Stories, three Pushcart Prize Anthologies, and O. Henry Prize Stories. She is a recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Writer’s Residency from the Lannan Foundation, and a fellowship from the Tanner Humanities Center. Thon’s fiction has been translated into French, Italian, German, Spanish, Croatian, Finnish, Japanese, and Farsi. Originally from Montana, Thon now lives in Salt Lake City, where she teaches in the Creative Writing and Environmental Humanities programs at the University of Utah. She spoke with FWR contributor Aaron Cance in the fall of 2011.

Melanie Rae Thon’s most recent books are the novel The Voice of the River (September 2011) and In This Light: New and Selected Stories (June 2011). She is also the author of the novels Sweet Hearts, Meteors in August, and Iona Moon, and the story collections First, Body and Girls in the Grass. Thon’s work has been included in Best American Short Stories, three Pushcart Prize Anthologies, and O. Henry Prize Stories. She is a recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Writer’s Residency from the Lannan Foundation, and a fellowship from the Tanner Humanities Center. Thon’s fiction has been translated into French, Italian, German, Spanish, Croatian, Finnish, Japanese, and Farsi. Originally from Montana, Thon now lives in Salt Lake City, where she teaches in the Creative Writing and Environmental Humanities programs at the University of Utah. She spoke with FWR contributor Aaron Cance in the fall of 2011.

Interview

Aaron Cance: Hello, Melanie! Thank you so much for agreeing to discuss The Voice of the River with me. Reading it was a beautiful and haunting experience, and I don’t think I’ll ever forget this story. I’d like to start with a few general questions, then perhaps shift into a few, more specific, ones about the new novel. I’m always curious about, and interested in, the formative years of writers whose work I enjoy and respect. Who were some of your earliest influences?

Melanie Rae Thon: By the time I started high school, I was not only reading but memorizing poems by Sylvia Plath and Walt Whitman, Pablo Neruda and e. e. cummings, passionate scenes from Wuthering Heights, quirky stories I found in journals. I rewrote sections of Johnny Got His Gun, imagining the speaker not as a soldier, but as girl my own age. I read the King James Bible without the filter of a minister or Sunday School teacher, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and a history of the Holocaust. These encounters jolted me into wakefulness, but also, strangely, miraculously, into love and wonder, a hunger to understand the gloriously diverse, mysteriously transient world around me.

Melanie Rae Thon: By the time I started high school, I was not only reading but memorizing poems by Sylvia Plath and Walt Whitman, Pablo Neruda and e. e. cummings, passionate scenes from Wuthering Heights, quirky stories I found in journals. I rewrote sections of Johnny Got His Gun, imagining the speaker not as a soldier, but as girl my own age. I read the King James Bible without the filter of a minister or Sunday School teacher, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and a history of the Holocaust. These encounters jolted me into wakefulness, but also, strangely, miraculously, into love and wonder, a hunger to understand the gloriously diverse, mysteriously transient world around me.

Who are writers who continue to influence and inform your writing today?

My dear and beautiful friend Mark Robbins once told me, “Writing is prayer, the dedicated concentration of your being on that which will help you become the person you know you should be.” This is very close to the teachings of the Desert Fathers who described Lectio Divina, divine reading, as the meditative approach, “by which the reader seeks to taste and savor the beauty and truth of every phrase and passage.” The writers who inform my writing are the ones who guide me toward a deeper contemplation of how I wish to live, to be, in the world. There are so many, and each is unique and important in his or her influence, but lately I’ve found myself reading or rereading something by Thich Nhat Hanh (the Buddhist monk) and John Berger every few months. James Agee, Tillie Olsen, and John Wideman help me understand the transcendent possibilities of inner speech and multivocal narratives, the importance of listening to everyone. When I enter the smoke and flames of Norman Maclean’s Young Men and Fire, I am transformed and inspired by his commitment to storytelling and research. There’s a gorgeous passage in a letter Dostoevsky wrote to his brother from prison:

Brother, I am not depressed and haven’t lost spirit. Life everywhere is Life, Life is in Ourselves and not in the External. There will be people near me, and to be Human among Human Beings, and remain one forever, no matter what misfortunes befall, not to become depressed, and not to falter, this is what Life is, herein lies its task. I have come to recognize this. This idea has entered my flesh and blood. . . . Never until now have such rich and healthy stores of Spiritual Life throbbed in me.

The Brothers Karamazov is a gloriously expansive exploration of this vision, and the recent translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky restores the nuance and complexity of Dostoevsky’s language.

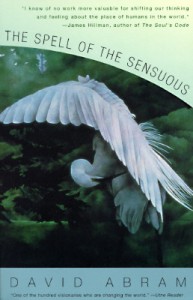

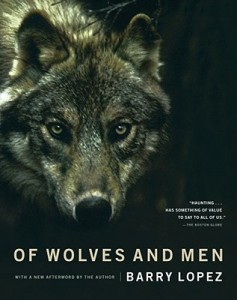

I could go on for days about books that inspire me to live fully, with compassion and curiosity and infinite wonder: the poems of Mary Oliver, The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram, Of Wolves and Men by Barry Lopez, The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel, Touching the Rock by John Hull, The Gospel According to Jesus: for Believers and Unbelievers, translation and guide by Stephen Mitchell . . . the more books I list, the more I leave out!

How has your conceptualization of, and personal philosophy about, writing craft evolved and changed over time, from your earliest efforts to your approach to The Voice of the River?

My own writing grows more spare, more elliptical all the time, closer, I hope, to the music of poetry. At seventeen weeks, the ears of the human fetus are open, ready to receive, exquisitely developed. We awaken in a waterworld, immersed in vibration and sound: the unceasing whoosh of blood through the uterine artery, our mother’s heart and breath, the surprising syncopation of our own miraculous heartbeat. We know the exaltation and pitch of voice: anger, fear, love, sorrow. Language to us is a polyphonic murmuration. We speak not only mind to mind, but body to body. Until each sentence sings, my work is unfinished. I read every line aloud—twenty, thirty, a hundred times—seeking not only sense, but tone and timbre and rhythm, hoping that through the fusion of meaning and music my words can touch anyone, fetus or mother.

In your acknowledgments for both The Voice of the River and In This Light, you’ve written that your students have shattered all opinions and challenged all assumptions. Describe a couple of ways that teaching has had a profound impact on your life?

In your acknowledgments for both The Voice of the River and In This Light, you’ve written that your students have shattered all opinions and challenged all assumptions. Describe a couple of ways that teaching has had a profound impact on your life?

My students constantly remind me how diverse human experience and perception can be, how little I know about anyone or anything! These revelations may be quiet or extreme. Last year my students and I were reading Thich Nhat Hanh’s The Miracle of Mindfulness. One woman described practicing mindful breathing while she was reading to her autistic son. A miracle indeed! Never before had he remained attentive while she read, but when she used her breath to calm her spirit, he too became tranquil. A thousand times a semester my students deliver to me a new understanding of grace.

Several years ago I taught a class called Healing Into Life and Death, exploring the ways people of different cultures understand spiritual and physical healing, the cycle of life and death, and the lives of individuals as they relate to the life of the family, the community, and the natural environment. Every student in that class amazed me! One woman gave bone marrow to her older sister when she was still an infant. Before she could speak, my student had saved a life! We performed poems from The Gift by the Sufi mystic Hafiz. A 200-pound tattooed video game addict read one poem in the voice of Sean Connery, and another in the voice of John Wayne. Hafiz is a holy man with a subversive sense of humor. My brilliant student brought his fourteenth-century work into the present through his wildly perfect interpretation. It’s endless, truly endless, the surprise and gratitude I feel in the community of the classroom.

You’ve been guiding writers in their formative years much longer than I’ve known you. Just since we first met, I’ve seen Jacob Paul’s moving debut, Sara/Sarah, come to fruition and was profoundly impressed to discover that Bruce Machart, author of the astonishing debut The Wake of Forgiveness, was a friend and former pupil of yours. I haven’t met very many people that have a heart as big and as encompassing as yours, and I know that you probably celebrate your students’ successes even more than your own. How has their success fueled your own work? Do your students motivate you just as much as you motivate them?

I always hope my friends and students will survive their “successes.” In Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl says:

Don’t aim at success—the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it does so only as the unintended side effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds true for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge.

I don’t think I’ve ever met a writer—or any artist—who didn’t long for external validation, but these rewards are fleeting at best, and never come close to the rapture one feels in the process of creation. Perhaps this is what fuels the desperate craving: when we abandon a piece of work, when we call it “finished,” we face the sudden loss of this passion.

I couldn’t agree more. I was having lunch with Jacob just a few days ago, and we were speaking to this. We discussed the challenges of producing fiction that has any significant degree of abstraction, how mainstream audiences don’t find it palatable and commercial publishers don’t see it as a viable publishing endeavor. A writer shouldn’t create art with the expectation of an audience, renown, or financial reward. A writer shouldn’t refrain from creating art because these things may never follow. A writer shouldn’t change the art with these things in mind. We agreed that you can only write to make art, to experience the miraculous act of creating, to discover something about yourself through your creation.

My friends and students inspire and motivate me when I see that they are able to stay true to their own visions and hear their inner voices, when they are not swayed by external rewards or dispirited by the stunning silence of absolute incomprehension. In one of the first classes I taught, a research report writing on the history of the Civil Rights Movement in America, many of my older, nontraditional students were learning to do research for the first time. (This was in the late 80s, in the days before students did research on the Internet, so these endeavors were infinitely more challenging!) Their discoveries and accomplishments were as thrilling as any I’ve ever experienced.

Yes, many of them composed impressive essays, but what remains with me even now is the awe we all experienced as we learned more about the movement, the incredible sacrifices, the history of violence and oppression. We were transformed together. Together we found the courage to take a difficult journey. We became a community, bound by shared purpose and dedication. Writing is always about discovery, and exploration allows for the possibility of transfiguration, the dynamic convergence of humility and enlightenment. The classroom is a place where we join hearts and minds and senses to become larger, more open than we are alone, more bold than we ever thought possible.

Yes, many of them composed impressive essays, but what remains with me even now is the awe we all experienced as we learned more about the movement, the incredible sacrifices, the history of violence and oppression. We were transformed together. Together we found the courage to take a difficult journey. We became a community, bound by shared purpose and dedication. Writing is always about discovery, and exploration allows for the possibility of transfiguration, the dynamic convergence of humility and enlightenment. The classroom is a place where we join hearts and minds and senses to become larger, more open than we are alone, more bold than we ever thought possible.

On a related note, I’ve gotten the sense from my own experiences in your novel workshop that your belief in the interconnectedness of every living thing is not a philosophy that begins when a reader opens The Voice of the River and ends when he or she turns the last page, but is something that you live every day.

Try to live! This is why I have to keep rereading and teaching books by Thich Nhat Hanh. This is why my students and I split our reading between science, spiritual texts, and literature. To be reminded, yes, again and again: we are intimately bound to everything that is, was, and will be. Even our bodies are complex biotic communities. Bacteria outnumber other cells ten to one, and without them we wouldn’t be able to digest our food or defend ourselves against many infections. Remnants of extinct retroviruses remain in our DNA, fossil records of the multitude of beings that influenced the course of our evolution. A fish that pushed itself out of the sea is our distant relative. The embryos of bats, lizards, birds, and humans are astonishingly similar.

There is a beautiful African proverb: I am because you are, and you are because we are. I like to think of this idea in the broadest terms possible: we are all part of the jeweled net: nothing exists except by connection to everything else in the infinitely miraculous universe. We mourn intimate loss, the deaths of ones we love, the extinction of species, but we are exalted by the spiritual belief and scientific understanding that through time and across space everything changes and continues. In The Heart of Understanding, Thich Nhat Hanh illuminates this idea with stunning simplicity. His example is a piece of paper, and he shows how all forms and forces in the universe are here: tree, soil, sun, rain—the logger who cut the tree, the wind that pollinated the wheat that made the bread that sustains him—all his ancestors are here, as are the worms who made the soil fertile. We can begin anywhere, with any being or any entity, and we will discover a web like this that opens forever in every direction.

In the film Planet Earth, Doctor Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury says, “Wilderness always speaks to human beings of Transcendence: in the widest possible sense it says, You as a Human Being are part of a System which is not just about your needs and your concerns. Like it or not, you’re part of something immense and very mysterious.”

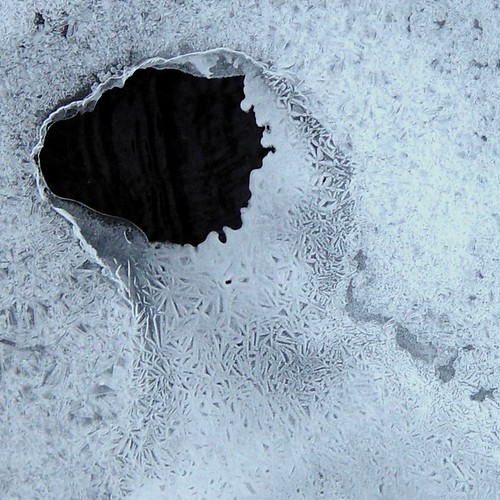

I think the single most painful image in The Voice of the River is the hole in the ice. It seems dark and beautiful in its own way as a doorway to some other place, but it is a heartbreaking image because it seems to also represent the hole that Kai Dionne’s disappearance has left in the fabric of the life that he left behind, perhaps we could say that it represents a hole in the jeweled net, an absence felt by all who were close to him. It almost seems to function in the story like a wound in the world that he inhabited.

Thank you, Aaron! This is a beautiful way to express the sense of loss I felt. Kai’s sections (the chapters in second person) are composed as love songs. I wanted to explore the different ways his love is manifested, the unique relationships he has with his cousins Iris and Tulanie Rey, his uncles Griffin and Roy, his half-sisters Juliana and Roxie, his dog Talia. This is what’s lost when a person disappears from our lives, the ongoing action of his physical love in the world. Juliana and Roxie will be forever changed by their love for Kai. His love for his sisters, his spiritual presence in their lives, will continue to transform them as they remember and reinvent shared experiences. But they will never again ride him up and down the stairs pretending he’s their pony. The hole in the ice reminds us of this profound physical absence.

You’ve written, in notes about The Voice of the River, of the way that the search for a missing child “becomes holy: a missing [emphasis mine] child belongs to, and is loved by, a whole community.” Had Kai not bolted out on the ice over the river to save his beloved dog, Talia, the community of searchers in the novel would never have come together, would never have had the shared experience of the search, a shared experience that has been revelatory for some of them. Is this novel also, perhaps, an impassioned plea to its readers to be mindful of the love that is possible all around them? To foster an awareness of a broader human family that we could all have if we would just come out of hiding long enough to embrace it?

A follower asked Jesus, “When will the Kingdom of God come?”And Jesus said, “The Kingdom of God will not come if you watch for it. Nor will anyone be able to say, ‘It is here’ or ‘It is there.’ For the Kingdom of God is within you.”

I believe this with my whole heart. During the last thirteen days of my father’s life on earth, I had a profoundly simple revelation: every moment of every day my siblings, my nieces and nephews, my mother and I had nothing to do except come here (to his hospital room) and love him and love one another. Despite the toxins flooding his body, my father gave and received love perfectly. Tolstoy says, “Love is life. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love.” When we are faced with extreme circumstances, we know this, we live this truth.

I carried my awareness everywhere: to the grocery store, the crowded street, down to the park in early morning. Everything and everyone seemed holy. I remained on the path in the months after my father’s transcendence. But as time passed, I wavered, I failed to love with that clarity. Love one another. It’s so simple to say; so challenging to practice in the frenzy and distraction of our daily lives! This is another reason teaching sustains me: it’s easy to love in the classroom; my generous students lift love lightly out of me.

I have always really been proud of my ability to stop anywhere and at any time I needed to in order to witness the beauty of the world around me reveal itself to me, whether it is by watching a prolonged process or being present mindfully to experience a single, shimmering moment that makes itself manifest to me, and is gone. In the novel workshop, that was reinforced, reinvigorated. The Voice of the River is flush with luminescent, transient moments that the reader witnesses. But the project as a whole was larger than that, wasn’t it? This seems, to me, to be a book about being a witness. Every revelation the reader has about one of its characters seems to encourage seeing with new eyes.

For more than twenty years I’ve been keeping what I call the Book of Wonders. Life begins here, in joy and astonishment. I see deer up to their ears in snow; a pigeon dying on my porch the day after Christmas; reflections of trees in the river, brilliant fish swimming in the treetops. One tanager swoops tree to tree, gold and orange, black-winged, silent: as I watch him fly, I feel my body rise as if I too have wings, a heart as strong as his to lift me.

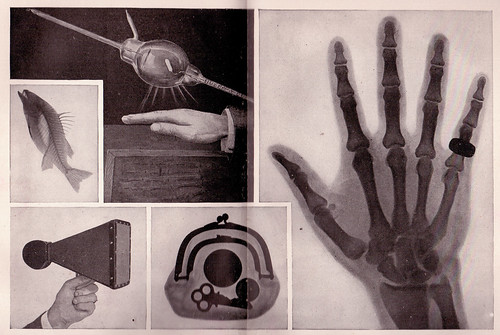

In the park, a woman drags a drunken man into the grass, feathering his face with kisses from her fingers before she leaves him. The x-ray of my sister’s back shows enormous bolts in her narrow spine, her fragile body transfigured.

I learn of medical miracles: marrow taken from the bone of a small girl, injected into the vein of her brother or sister; titanium ribs perfectly formed for scoliosis patients; a baby who thrives in her mother’s womb after the woman is shot in the belly. My father survives nine coronary bypasses, three heart attacks, five strokes. When all his organs finally fail, we learn his precious pacemaker cannot be transplanted to a human being, so we offer it to a golden Labrador. Now every dog I see fills me with spontaneous delight, my father’s love, a living vision of his resilience.

My work as a writer begins here, with strange and miraculous tales, the daily prayer of attention. I’ve filled more than seventy volumes. Making stories is not the goal: I wish only to be more alive, more mindful, more reverent. Keeping The Book of Wonders restores me to the possibility of grace in every moment.

So yes, you’re right, the project as a whole becomes larger, but it begins with “attention taken to its highest degree.” Simone Weil says this is the same thing as prayer: “it presupposes faith and love.”

The presence of the lost children in The Voice of the River is tragically fitting. Each of these children, present though they may be in the story, is missing to someone. Missing children appear in your 1997 collection, First, Body, and in the new story, “Heavenly Creatures,” that appears in In This Light, the story collection published by Graywolf Press just a bit earlier this year. Talk about the presence of missing children in your work. Is their presence in the writing a way of giving voice to the voiceless? Of giving presence to the absent or of rediscovering the lost?

I want to go back to your comment on witnessing. I had my first intimate encounter with homeless children when I was sixteen and a friend of mine was sent to a juvenile detention center. (I’ve fictionalized his story in “Iona Moon,” another piece in the collection In This Light.) When he returned a year later, he was irrevocably altered, brain damaged from fights or drugs or beatings—he could never tell me. His parents refused to let him come home, and he lived in sheds he found or made shelters from sticks and garbage bags.

Years later, when I lived in Boston, my “apartment” was an attic room without insulation. I froze in winter, fried in summer. Still I knew how lucky I was to have shelter, food, a job, a doctor. I walked everywhere, miles and miles every day, through all parts of town, tame and dangerous, in all kinds of weather. I encountered the homeless, the poor, the extravagantly wealthy, the addicted, the recently immigrated, the excessively educated.

One brutal winter, a storm surged up the coast every weekend. I lost power for days at a time. Pigeons flapped at my dark windows. I walked. And there they were: the kids, throwaways and runaways, the unloved and unlucky. The emaciated Haitian refugee shivered in Harvard Square, playing his guitar, trying to earn a few dollars. He was a brilliant musician, but his eyes were yellow where they should have been white. I thought he would die soon. The man with no fingers slept in a doorway and could barely move; as I passed, he opened his bare palm and lurched toward me.

The lives of the people I saw on the street became vivid to me, intensely personal. I began to imagine how those children might survive, who they might love, why they were out there. I began composing “Xmas, Jamaica Plain” (another piece included in In This Light), dreaming the lives of Nadine and Emile.

In 1998, I worked with a juvenile prosecutor in my hometown (Kalispell, Montana), doing research for my novel Sweet Hearts. He told me he believed there were 300 homeless kids in the area. These are the children in “Heavenly Creatures.” By the time I started exploring The Voice of the River, I imagined their numbers swelled to 700. But it’s strange: as numbers increase, they become even more abstract, weirdly inconsequential. Stories remind us that each life is precious. Nadine, Emile, Matt Fry, Trace, Peter Fleury, Flint Zimmer: each missing child has a history of love and loss, a passionate story to tell us.

Like you, like all humans and perhaps many other creatures, I have received the gift of mirror neurons, pathways in our brains that allow us to experience “Kinetic Empathy,” the sense that when you witness something, you “feel” as if it is happening to you. This may be physical (you watch someone fall and scrape skin on gravel and you flinch in pain), or emotional (you see a teacher ridicule a classmate and feel the burn of humiliation). Kinetic empathy may become unbearable: powerless or paralyzed by fear, you watch one person torture another. Years later, the memory continues to haunt you: you see yourself as both victim and perpetrator.

Like you, like all humans and perhaps many other creatures, I have received the gift of mirror neurons, pathways in our brains that allow us to experience “Kinetic Empathy,” the sense that when you witness something, you “feel” as if it is happening to you. This may be physical (you watch someone fall and scrape skin on gravel and you flinch in pain), or emotional (you see a teacher ridicule a classmate and feel the burn of humiliation). Kinetic empathy may become unbearable: powerless or paralyzed by fear, you watch one person torture another. Years later, the memory continues to haunt you: you see yourself as both victim and perpetrator.

This too must be transformed by love, a willingness to remember, to re-invent and re-imagine. Anna Deavere Smith says she recognizes the gap between herself and the people she represents in her plays. The thrill of the experience for writer or actor, viewer or reader, is to move into that space, to become other than oneself while still acknowledging and respecting the infinite unknowable mystery of every living being.

Rumi says: You become bewildered; then suddenly Love comes saying, “I will deliver you this instant from yourself.” Love, not art, is the purpose; but for some, witnessing and rendering and imagining stories is the process and the path to understanding.

You’ve been working on The Voice of the River for quite some time. Looking back at the entire process, were there points of its development that stand out to you as particularly profound or important? Were there any points in its development that were revelatory to you?

I loved going to the park in early morning and speaking with the pigeons in their language, trying to imitate their tender voices. When I composed Daniel Sidoti’s sections, I loved the owls and the mountain goats, the ways Daniel taught me to perceive them. Every moment of the experience still feels revelatory to me. I could open the book at random, point to any passage and tell you a story about the ways in which that exploration continues to open my vision and deepen my sense of awe for all the living beings and potent entities I encounter. When I imagined the hibernating bear giving birth to two cubs, I lived inside the den, trying to render every detail from their perspective. I can’t really know what bears sense and think, but I can move outside myself, and this freedom, this joy, is extravagant.

I don’t think I’ll ever forget the experience of reading this novel. Will these characters continue to haunt you?

I hope all the living beings, human and more-than-human, will continue to change and open me. I believe they will. I trust them.

Further Links and Resources