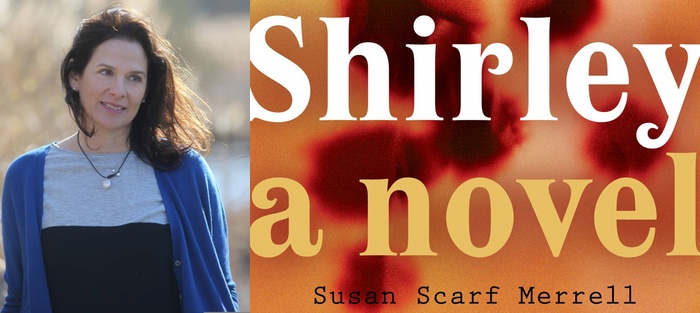

Susan Scarf Merrell knows how to juggle. She completed Shirley, her second novel, while teaching in the MFA program of Stony Brook Southampton and also serving as fiction editor for TSR: The Southampton Review. We spoke in June, ten days after Shirley’s publication by Blue Rider Press, a Penguin imprint. Merrell reflected on the combined influence of work as teacher and editor on her writing. And she mused on the surprising, fated way in which reading and admiring Shirley Jackson’s fiction led to her fascination with the author, and ultimately to writing Shirley. Merrell’s novel—love story, mystery, and ghost story combined—is a fitting and original homage to Jackson. Reading the author’s fiction and letters was Merrell’s initial way in to the world of this novel, an imagined world of Jackson’s life as seen through the eyes of Shirley’s young protagonist Rose.

Ever since Merrell and I met in graduate school seven years ago, we have enjoyed an ongoing conversation about writing and life—and about what happens when you’re making other plans. As we settled into this telephone chat, Merrell at her kitchen table in Long Island, I on my screen porch 300 miles south in Maryland, she was catching her breath after an early morning emergency vet visit for her beagle.

Interview:

Ellen Prentiss Campbell: I’ve been wondering how you see your teaching and editing intersecting with your work as an author.

Susan Scarf Merrell: People say you don’t want to teach, you don’t want to edit, that it will ruin you for writing. For me, it’s the opposite. Teaching and editing don’t tire me out or drain me. For me the hardest part of the writing life has been the loneliness, the isolation. Thinking about other people’s work structurally is exciting. Working on editing pieces for the next TSR issue moves my own writing process forward. Being edited is not the same as being torn apart. I know so well now that an editor always has her writer’s interests at heart.

The three kinds of work—writing, teaching, and editing—all have an effect on the others. You do have to keep it in balance and perhaps because of our semester schedule, and the schedule for the TSR issues, I can dance between the three.

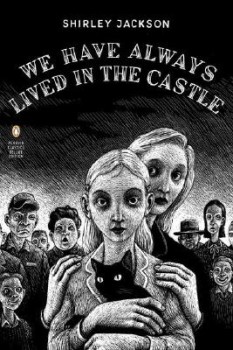

And being able to balance might also be age-related—being able to be more efficient, and less ego-involved than I would have been a decade ago. A boon of my long dry spell after my first novel (A Member of the Family, HarperCollins, 2000) was that I processed the “Oh, I haven’t done what I was supposed to do.” I can bring that to the teaching, and my own writing. When I started in the MFA program at Bennington, I knew I wanted to write about domesticity in my fiction, and I knew that what I wanted to write about was darker and a little stranger than what most people think of when they think of domestic fiction. My first semester at Bennington, it was novelist Rachel Pastan who suggested I read Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle (Viking Penguin, 1962). I think perhaps I’d read it as a teenager, but this time it had an explosive, mind-bending effect on me. I started reading all of Jackson’s work with increasing, even obsessive, interest. But the biggest surprise was getting back to Bennington the following semester and learning that Jackson had spent much of her adult life in North Bennington, and that her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, had been a much-loved instructor at Bennington College. It was the first of many moments in the writing of Shirley when I felt as if I were on a path guided by unseen forces. Later, learning that Shirley Jackson was extremely interested in witchcraft, I started to joke that she was guiding my hand from beyond the grave. And sometimes I didn’t really feel as if it were a joke at all.

And being able to balance might also be age-related—being able to be more efficient, and less ego-involved than I would have been a decade ago. A boon of my long dry spell after my first novel (A Member of the Family, HarperCollins, 2000) was that I processed the “Oh, I haven’t done what I was supposed to do.” I can bring that to the teaching, and my own writing. When I started in the MFA program at Bennington, I knew I wanted to write about domesticity in my fiction, and I knew that what I wanted to write about was darker and a little stranger than what most people think of when they think of domestic fiction. My first semester at Bennington, it was novelist Rachel Pastan who suggested I read Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle (Viking Penguin, 1962). I think perhaps I’d read it as a teenager, but this time it had an explosive, mind-bending effect on me. I started reading all of Jackson’s work with increasing, even obsessive, interest. But the biggest surprise was getting back to Bennington the following semester and learning that Jackson had spent much of her adult life in North Bennington, and that her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, had been a much-loved instructor at Bennington College. It was the first of many moments in the writing of Shirley when I felt as if I were on a path guided by unseen forces. Later, learning that Shirley Jackson was extremely interested in witchcraft, I started to joke that she was guiding my hand from beyond the grave. And sometimes I didn’t really feel as if it were a joke at all.

So, two years later, I left grad school in love with Shirley Jackson. I thought I wanted to write a biography. I love research and facts, and the limiting nature of facts on narrative. But there’s no getting around that I’m a maker up of stories. So after eight months of research for the biography, instead I started writing a memoir of me searching for answers to questions Shirley Jackson’s work raises for many women about being a woman and a writer. That didn’t feel quite right either. I wanted to write about why Jackson mattered, yes, but even more I wanted to use what I had learned from her work and from her life to create what I guess you’d call an homage to her. And I really struggled—how to tell the story, what the story really was—for a very long time. Until one day, taking a walk in the woods with my dog, this vision of Rose sprung to life fully formed, without any warning!

Your novel’s protagonist, your narrator.

Yes. It was as if I knew her, and then I knew. I’m writing a novel. And it’s her story. What she sees, because of who she is and where she comes from, because of the limitations that her life story provides.

I recall getting some of those first draft chapters—as a novel, I think.

It was as much a shock to me as anyone else. Literally Rose came to life—the idea of her as a flawed narrator without the tools to look at others and judge them.

Like the way she watches Shirley Jackson and her husband Stanley Hyman, while she lives with them.

I knew Rose immediately and completely, crazy as it sounds, and all of a sudden I was in this dream and it was Rose’s dream. And so writing this novel became a really different experience. I’ve always done research, fallen into research with intensity. And I did the same thing here. But I barely looked at the research once I started the actual writing. It was what Rose knew and saw that I worked with. And there were odd things that happened. With this project, every time I turned around, the world was pushing the project along. There were all these insane coincidences.

What, for example?

I taught a workshop several summers ago at the Southampton Writers Conference, and at some point I mentioned that I was working on a novel about Shirley Jackson. After the class one of the participants came up to me and said her husband had been a childhood friend of Shirley Jackson’s children in North Bennington. How in the world could the wife of a childhood friend of the Hyman family from Vermont end up in my writing class on the Eastern End of Long Island? But she did. Soon after, I had the good fortune to meet her husband and he understood the project, and was very helpful to me. He’s died since, but I am so grateful for having met him. And there were other odd coincidences. I would make up a character, and then meet someone with the same name who lived precisely where I’d imagined, or I’d be at a party and someone I’d known for years would suddenly come out with a story about having met Shirley and Stanley that was tremendously helpful. All these coincidences.

Even that you came to Bennington, in the first place. And that Rachel said read Shirley. What a lot of coincidences, indeed! But the only thing that matters, as you say Shirley said, is that what happens be true in the world of the story.

That’s the gift reading Jackson gave me. Understanding that as a fiction writer, you make the rules of the world of the story. What matters is that whatever happens has to be true in the world of the story. That’s Jackson’s great, freeing notion. A story has to be plausible within its own world. When you’re reading, you need to believe it completely. But no fiction needs to be true outside the world on the page. It needs to be true for the characters and then it feels true and fulfilling to the reader. And I use that. In my writing. And in my teaching—I coach and edit with it in mind.

Tell me more about that. How does that apply to your work with students, and writers submitting to the TSR?

There are lots of kinds of stories that I myself don’t write, but if my students want to, I want to help them be the best writers of those stories they can be. I tell my students, I’m not trying to write your story; I’m trying to make events true in the world of your story. That’s my Shirley Jackson maxim. And I use it when I’m teaching graduate students in our program’s practicum on editing. Our MFA program has lots of practical training—not simply writing, but also editing the literary journal, teaching at both the high school and college levels, even arts administration. And when I’m teaching or editing, I have to get into the head of the person who is writing the story. I have to get inside their creative world. I know I’m not the only writing instructor who does this; it’s really the key to teaching well. And sometimes students are surprised at what I’m seeing—and sometimes I’m wrong about what I see. Creative work is like that. The form, the intent isn’t always obvious until you’ve finished a full draft. And with longer work—if you don’t know where someone is going, all you can say is keep going. Then at the end, you can see the whole.

I’ve heard you say: “Keep going until you touch the end of the swimming pool.”

Right. I’m not a big fan of re-reading your own work. There’s nothing more undermining than to keep going back self-critically when the only job is to get a full draft on the page. Keep pounding forward. Get all the id into the first draft. And then, I’m a tremendous advocate of reverse outlining.

How do you do that? I’ve been reading about a version of the technique in Jeff Vandermeer’s Wonderbook.

Before the manuscript is cold, I make an outline. I take big index cards for each chapter, and make notes about what I’ve done. Who’s in the chapter? What do they do? How does the time flow? Where are the people who aren’t there? What events begin and end? What gestures and ideas are recurring, and should they be? What are the ideas the characters are having? What are the missed opportunities? I pin all the cards on the wall and stare at them. That’s when I let the manuscript rest. And I might stare at my wall for a number of weeks. Things emerge—patterns. I jot them onto the cards. I start to see what to drop into the story. What chapters are missing. What’s in balance and what needs to be shifted. This is where you might see that you have two characters who fulfill the same function and can be combined into one. Or that you have placed a bigger scene too early, or a smaller one too late. Everyone should be doing reverse outlining. It tells you what you’ve done.

Good writing, editing, teaching—they all require work and practice. But a little practical magic, too, right? And your work, and Shirley Jackson’s, they’re infused with magic.

She was extremely good at locking down the fabulous—making it true in the world of the story. You cannot write something unless you believe. Unless you make it true. And there are ways to do that, to make the unbelievable seem absolutely plausible on the page. Reading Shirley Jackson can absolutely teach a writer how to communicate the fantastic in the most pragmatic and straightforward manner.

I’m thinking about what you said about getting inside the world of the story, and inside the head of the character you’re writing or the student you’re teaching, the writer you’re editing. There are sections in Shirley where your protagonist, Rose, is actually trying to write as if she is Shirley.

Yes. Those sections came into being very early on, perhaps even when we were still in grad school, as a kind of free writing exercise for me. They weren’t in earlier drafts of the novel, but at a certain point I realized they were perfect for Rose, precisely the kind of thing she would do. She admires Shirley so much, and so wants to be like her. And I so understand that. Despite the complexities of Shirley and Stanley’s lives, much of which has to do with the time and place and world they inhabited, I think they were a remarkable pair and had a remarkable partnership.

Could you write about someone you didn’t admire?

Oh, I think so. But Rose couldn’t. She is a worshipper looking for a hero.

Rose certainly admires Shirley, and Stanley, idealizes them at first. She’s a young woman literally embedded in the Hyman household. Soaking up every detail of what they do, what they eat, what they drink.

Rose certainly admires Shirley, and Stanley, idealizes them at first. She’s a young woman literally embedded in the Hyman household. Soaking up every detail of what they do, what they eat, what they drink.

I needed Rose to tell this story. It’s all about her point of view. Her openness, and her closed-ness. Her vulnerabilities. Her neediness. Without Rose, there wouldn’t be a mystery, I think. She’s the reason the novel isn’t a novel of domesticity, but of something a little stranger. Or at least that’s what I hope the reader finds. That’s the kind of book I myself like to read.

Who, besides Jackson, for example?

I like Daphne DuMaurier and Iris Murdoch and Dawn Powell. Judith Rossner. Megan Abbott. Kate Christenson. Meg Wolitzer. I really liked Gone Girl. And there’s nobody like Joyce Carol Oates. This used to be a narrow field but now there are so many women who write about women in dark and interesting ways. Who aren’t idealizing what it is to be a woman or a mother, but instead examining these roles with a humor and intelligence akin to what Roth and Updike and Bellow were doing with manhood in the ’60s and ’70s.

The Hyman’s domestic situation here—it’s dark, and mysterious. Affairs. An unsolved murder. Witches, spells.

Oh, witches—that’s one way to take control of the world, one method. But Shirley Jackson—she was in control of her own gifts. One thing she wrote in her journals that I’ll never forget is “Writing is the way out.”

Did she say that? I love it. It was the slogan in the children’s room at our library: Reading is the Way In, Writing is the Way Out.

She read widely. She had—and Stanley did, too—a tremendous wealth of knowledge, about folklore and ballads and mythology and psychology and so much else. They were so very smart. And also, Shirley lived in a different time—no facebook, no tweeting. For fun? She cooked, she wrote. She read and read. There are so many levels of text in everything she wrote. Look at the epigraph to Shirley, for example, which is from The Haunting of Hill House—you’ll find everything embedded there, from architecture to the natural world, from Hamlet to Poe. So much of her writing is layered this way, so that you can enjoy it the way it is, but also find greater depths in it, references to fairy tales or history, to poetry or mythology.

She read widely. She had—and Stanley did, too—a tremendous wealth of knowledge, about folklore and ballads and mythology and psychology and so much else. They were so very smart. And also, Shirley lived in a different time—no facebook, no tweeting. For fun? She cooked, she wrote. She read and read. There are so many levels of text in everything she wrote. Look at the epigraph to Shirley, for example, which is from The Haunting of Hill House—you’ll find everything embedded there, from architecture to the natural world, from Hamlet to Poe. So much of her writing is layered this way, so that you can enjoy it the way it is, but also find greater depths in it, references to fairy tales or history, to poetry or mythology.

What about your own reading? What are you interested in, as a writer, as a teacher?

Shirley and Stanley set a daunting example, I think. There’s so much to know, about everything! I will spend the rest of my life filling in the holes in my knowledge and not even make a dent in what I want to know. And I learn so much, too, from teaching, from my students. For example, the first time I taught the Haruki Murakami story “Barn Burning,” I taught it by itself. It’s a story I love and has such brilliant pacing, such a perfectly embedded obliqueness. A student compared it to Faulkner’s “Barn Burning.” And what the student picked up really added to the reading of the Murakami. So the next semester, I taught the stories together. And everyone who reads the Faulkner brings a different understanding to the Murakami. I love all the wonders of short stories. With teaching—I’m always looking for deepening experience.

This summer what are you reading–in your spare moments between writing, teaching, editing, and book touring?

Right now, the top of the pile of books I am about to read? I just finished Dinah Lenney’s beautiful book of essays, The Object Parade. And now I’m in the middle of Laura Van den Berg’s stories, Isle of Youth. They’re wonderful. Next is Clare Vaye Watkins’ Battleborn. Rivka Galchen’s American Innovation. Bret Anthony Johnston’s novel Remember Me Like This. Zach Lazar’s I Pity the Poor Immigrant. There’s so much terrific fiction to read right now!

Indeed there is, and Shirley is one of the books to be read–right now!

Coda:

It struck me throughout our conversation that a writer may choose her subject—Merrell chose Jackson—but a subject may also choose the writer. This partnership seems to me a case of mutual attraction. Somehow, from beyond the grave, Shirley Jackson herself chose Merrell. And after all, aren’t there more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of by philosophers? Merrell’s reading and research led her in to a deeply imagined but deeply rooted fictional world. And to our delight as readers, Merrell had to write her way out.