I first met Dariel Suarez in his capacity as the Education Director at Grub Street, the Boston-based creative writing center where I periodically teach seminars in fiction. I was and am impressed by the combination of generosity, thoughtfulness, and passion Dariel brings to the teaching and the writing of literature.

Our paths soon crossed elsewhere: in Havana, where he was visiting family and I was running, with Alden Jones, an annual writing workshop. I’d been traveling to the country multiple times a year since 1999 in the course of my parallel career as a lecturer and international programs director, and in this line of work I’ve met Cubans who are writers, lawyers, doctors, biologists, entrepreneurs, educators, community leaders, city historians, architects, choir directors, taxi drivers, farmers, fishermen, and visual and performing artists of every imaginable stripe. A number of these individuals have become good friends and colleagues over the years, and it’s a particular honor to include in this category a fiction writer and educator as talented as Dariel, who grew up in Havana before leaving for the U.S. in 1997.

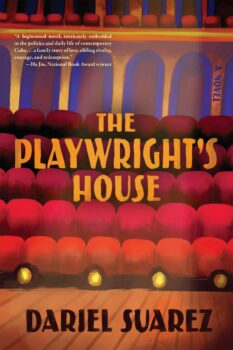

Over the course of eleven beautifully composed stories, Dariel’s debut collection, A Kind of Solitude (Willow Springs Books), which came out two years ago, portrays the harsh realities of Cuban life and the inherent humor and resilient spirit of the Cuban people. “Suarez masterfully collides the personal and the political,” noted The Paris Review, “moving characters and circumstance toward each other like pieces on a chessboard.” Needless to say, I was thrilled to receive an advance reader’s copy of The Playwright’s House, his debut novel, which is the main focus of the conversation that follows. The new book is out this month from Red Hen Press.

Interview:

Tim Weed: The first thing I noticed about the novel is the setting. Havana is a complex city, and one whose essences are often difficult to capture in words, but you really put us there. In addition to your portrayal of the struggles of daily life in Havana, the way everyday Cubans think, and what they’re up against, you give us the essential feel of the city; not only the sights, sounds, and smells, but something of the ineffable spirit of the place. My wife is an oil painter, and she creates these incredibly beautiful, dream-like landscapes that are loosely based on scenes she’s seen in real life, but in the end they’re completely made up. She swears by the fact that if they weren’t made up—if they were too closely based on a photograph, for example, or on something that was right in front of her while she was painting—they wouldn’t feel as real. For me, it’s a similar process in fiction. You have to recreate these places you know in order to bring them alive. All of this is by way of asking you about the Havana of The Playwright’s House. How much of it was based on memory, and how much on research? How did you go about “assembling” or “creating” your story-world in a way that gives it such a compelling feeling of reality?

Dariel Suarez: My starting point for Havana was a combination of memory—the place I grew up in and lived for fourteen years—and research. I drew quite a bit from what I could recall, particularly when it came to feel. The childhood neighborhood of the main characters is based on my own, for instance, so I knew its nuances and cultural specificities quite well. But because I left at a young age, my relationship with the larger Havana was still one of exploration, so I had to essentially interview my parents, and especially my father, who worked as a driver before becoming a journalist and knew every part of the city. I drew maps of places based on my conversations, then looked up photos and videos to get some visual references. I got the opportunity to visit Havana a few years back before my last round of revisions, so I was able to compare what I’d written with a more recent reality, and I was pleasantly surprised at how much I’d gotten right. I did add some touches here and there for things you can only notice in person, but overall I learned that memory is powerful not just because it can be accurate so many years later, but also because there are things in your subconscious which might come out in the process of writing, and when you see them again, you recognize them immediately not as part of your imagination, but as a dormant memory. At a micro level in terms of scene, I did imagine many of the details, but a combination of the above definitely grounded me and allowed me to continue the exploration that was abruptly cut off when I left as a teenager.

Dariel Suarez: My starting point for Havana was a combination of memory—the place I grew up in and lived for fourteen years—and research. I drew quite a bit from what I could recall, particularly when it came to feel. The childhood neighborhood of the main characters is based on my own, for instance, so I knew its nuances and cultural specificities quite well. But because I left at a young age, my relationship with the larger Havana was still one of exploration, so I had to essentially interview my parents, and especially my father, who worked as a driver before becoming a journalist and knew every part of the city. I drew maps of places based on my conversations, then looked up photos and videos to get some visual references. I got the opportunity to visit Havana a few years back before my last round of revisions, so I was able to compare what I’d written with a more recent reality, and I was pleasantly surprised at how much I’d gotten right. I did add some touches here and there for things you can only notice in person, but overall I learned that memory is powerful not just because it can be accurate so many years later, but also because there are things in your subconscious which might come out in the process of writing, and when you see them again, you recognize them immediately not as part of your imagination, but as a dormant memory. At a micro level in terms of scene, I did imagine many of the details, but a combination of the above definitely grounded me and allowed me to continue the exploration that was abruptly cut off when I left as a teenager.

It’s funny, I meant to ask about that. In particular, it struck me that while you and your family left Cuba, two of your main characters choose not to leave. Without giving too much away, would you care to talk about that?

As a writer, I’ve always been interested in characters whose lives are different from mine. It seems to me like a lot has been written in the U.S. about Cubans who left the island or were forced into exile, but not so much about the folks who choose to stay. I wanted to explore the emotional and psychological reasons for people who prefer to remain there, even if they’ve had an opportunity to leave, or if their loved ones have migrated. For most it isn’t even a choice, of course, but when it is, rarely does it feel like an easy decision. I’ve found that folks in privileged positions often don’t truly grasp just how traumatic migration can be, especially if it was driven by economic or political reasons. People talk about culture shock and assimilation, but it is so much deeper than that. Even though I’ve never regretted it, it was still a painful experience for me. I cried a lot the first two years. I missed everyone I left behind. A part of me will always miss Cuba, no matter how much I get to visit. Writing about characters who decide to stay is a way to maybe imagine a different life for myself, and to better understand the folks who are still there, to feel closer to them.

For me a particular strength of The Playwright’s House is the characters, especially the four well-drawn and highly sympathetic central players: the cerebral and tortured protagonist, Serguey; his more extroverted and impulsive brother Victor; and the two women in Serguey’s life: his wife Anabel; and her sister, Alida. Can you talk about your process for developing characters? Is it similar to how you work with setting? Do they tend to be based on people you know, or is that just a point of departure?

In my case, characters are much more their own entity. I usually start by knowing what their main conflict and obstacles will be, and from there I begin to develop their inner lives, their personalities and dreams and fears. I search for the tension between who they are or want to be, and what’s happening to them or around them. That’s where the good stuff lies for me, where I get to see the best and worst in them. I also search for characters who are closely connected to each other, or who are forced to be connected by circumstances. Their interactions open a lot of doors in terms of exploration, of unexpected intimate moments. In this novel, none of the central characters are based on people I know, though some of their traits or backstory might be informed by something in my own life. Ultimately, I prefer to step mostly outside or beyond myself in fiction.

It’s interesting that you mention connections and interactions, because another thing this novel does very well, in my view, is to portray the evolving relationships between the four major characters. You might call these subplots, as they’re secondary to the novel’s extremely tense central plot, but whatever you call them, they contribute greatly to the interest and satisfaction of the reading experience. How do these relationship dynamics evolve in your writing practice? Are they clear from the beginning or do they change and develop as you write and revise?

It really depends. I usually have a general idea of the dynamics between my central characters, as I like to outline, plan ahead, and interrogate possibilities from the get-go. I don’t commit to a writing project until I have a clear vision for it. However, in the process of drafting and revising, characters evolve and surprise you, so I’ll go down a different path if I think there’s something there. In this case, I knew I wanted these four characters to be inextricably linked through the circumstances, and for their inner lives to be tested. But the specific ways in which they ended up interacting and challenging each other came more naturally as I wrote. A strategy I use is constantly questioning what I’m trying to get out of each scene, each moment, when the characters are together. I don’t settle for the first thing. I keep pressing and asking “but what if?” until I arrive at what for me is a satisfying level of conflict or tension, at the kind of situation that will bring out the gray areas: the characters’ flaws, contradictions, nobility, etc.

Can you talk a little about your literary influences? In particular, I was reminded of Leonardo Padura—but that might just be that it’s about a character trying to piece together a troubling mystery set in Havana. But are there authors you feel particularly influenced by, past or contemporary?

I haven’t read a ton of Padura, though I’ve been familiar with him and his work since I was a kid, of course. Lately I’ve been curious about checking out his books more deeply, since I’ve been increasingly interested in infusing elements of genre—particularly mystery, thriller, or noir—into my work. Plot has always been important to me, so even though I consider my writing literary, I’m a huge fan of writers (and filmmakers) who have compelling and energetic plots. These days, some of my favorite authors are people like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Juan Gabriel Vasquez, Javier Marías, Elena Ferrante, Mariana Enriquez, Yuri Herrera, and Idra Novey. All of these writers, in my opinion, know how to grab you and not let go. Their work has depth of character and culture, sometimes political or historical elements, but it always moves. There are essential events or questions that, if not solved, must at least be actively explored. I’ve always been naturally drawn to work which feels nuanced and intellectually stimulating, but that never bores or feels like navel-gazing. And as you can see in the names I mentioned (believe me, I left many out), I’m a big proponent of international lit.

Padura is wonderful, I think, for the genre elements you mention, for his immersive portrayals of Havana, and for a lot more besides. I also admire a number of the authors you mention—and thanks for the additions to my reading list, because there are a few that I’ve yet to have the pleasure of reading. But let’s get back to Havana and your vision of it. Something that I think you capture rather well in The Playwright’s House—and indeed, that is central to the lives of your main characters—is the dedication to the arts that one can’t help but notice in Cuba. There is a generalized level of artistic accomplishment that is to me one of the most admirable—and bittersweet, and contradictory—aspects of Cuban society, especially in the face of the terrible hardships and obstacles faced by its people. Can you talk about this a little?

The arts in Cuba are definitely a complex area, and this is one of the reasons why I picked them as a central theme in the novel. In a place like Cuba, there’s always tension between arts and politics, because of the controlling nature of the government. Artists often have to compromise, whether consciously or not, if they’re making art under a repressive regime. Culturally, there’s a lot of reverence when it comes to all forms of art, and there are incredibly talented people on the island. The lack of commercial influence or expectations makes for very ambitious, creative work. But it also means that the majority of artists struggle financially, in addition to having to deal with the politics, so even though to an outsider it might look vibrant and culturally rich and celebratory—and it can absolutely be these things—there’s sometimes a darker, more difficult and complicated side. I wanted to show the compromises and tough decisions some people have to make, as well as instances when artists might say, all right, that’s enough, I need to express or act on my socio-political opinions, no matter the consequences.

The Playwright’s House paints a compelling picture of Havana as a tense and difficult place to live, and I suspect that many of my Cuban friends would feel a sense of recognition. But in certain moments you also seem to come down on one side of what strikes me as a highly polarized debate about the history and legacy of the Cuban Revolution. I’m curious about your views on this as a novelist. My first book, Will Poole’s Island, features another idealistic movement with a controversial legacy, though of course a much more historically distant one: the Puritans of seventeenth-century New England. Writing it, I often found myself laboring within the constraints of a dramatic plot to strike a balance between using poetic license to provide my protagonists with the strongest possible opposing forces to strive against, while also trying to do justice to the complexities of history and of human nature. As Chekhov wrote, “Let the jury judge them; it’s my job simply to show what sort of people they are.” How did you balance your hard-won political views with the novelist’s mandate to give every character their due? And how have politics influenced and shaped the novel?

Thank you for this question! I guess I don’t see it as coming down on one side. The political reality in Cuba is only complex in how it impacts people and what it brings out in them. It is a fact that there are political prisoners on the island. People are persecuted and abused. Many have been exiled as a result. What’s happening now with the San Isidro Movement serves as an example. There’s one political party and government entity that, for over half a century, has controlled the press, the economy, the laws, and the people. To ignore these things would be a disservice to not just Cuba but truth. And I see that as one of my responsibilities as a writer: to get at some kind of truth. A lot of what I’m saying here and what’s in my novel, a Cuban writer living there would likely not get away with writing or saying, let alone publishing, without some kind of repercussion. The other side of the coin I feel like I also show in my novel, and I do give each character their due. I empathize with and try to understand even my antagonists. Maybe outsiders expect for there to be neatly contrasting ideologies which are equally sympathetic, morally sound, or questionable. I just see it as more complex—with fear, hypocrisy, and hubris playing a big part—and I believe someone who hasn’t lived in Cuba as a Cuban has no real way of understanding the depths of it all. I myself don’t claim to understand it. I will also add that there’s a tendency in the U.S. to want to separate politics from fiction. This is why so much of renowned white American fiction, especially in the last few decades, largely ignores or miserably fails at portraying race, class, and BIPOC immigrant culture, even though these things are not only prevalent in this country, but at the core of its identity. It takes vast amounts of privilege and naiveté to ignore them, to hide behind some dictum that we must remain neutral as artists. To my mind, this position makes fiction so sterile and insular as to render it almost irrelevant. I’m not trying to convince anyone of anything with my novel. But I won’t shy away from the fact that I wanted to show an important truth, no matter how uncomfortable it might be to wrestle with it, or how much it might shatter or resist a more romanticized or seemingly balanced view of the island.

I think the novel does address these complexities in a way that is both challenging and thought-provoking, and I agree with you that fiction is inherently political. I suspect Chekhov would agree as well, though when it comes to creating fiction with integrity I believe his point stands. But many of my Cuban friends would be quick to point out that U.S. society is not without its own grave human rights failings, particularly around issues such as out-of-control gun violence, extreme inequalities in income, education, and the availability of medical care, and the systemic racism inherent in our military-style police practices and the demographics of our prison system. They might also point to the vast damage the U.S. embargo has done to the lives of everyday Cubans over six decades (as opposed to the interests of the government, for which the embargo has in some ways been useful). This is a policy that many Cubans I know who are committed to staying in the country would really love to change.

Anyway, our allotted space is rapidly dwindling, and I wanted to be sure to give you a chance to turn your eyes to the future. What are your goals as a fiction writer going forward? Are you willing to discuss what you’re working on next?

I’d like to continue developing a body of work—novels, stories, and essays—that explore not just Cuban identity in and outside the island, but intercultural experiences as well. My current work-in-progress is a novel set in South Florida, which deals with immigrant trauma, human trafficking, and the failed promises of the American dream through the lens of a multicultural family. I’d like to write other books set in Cuba, too, and have some concrete ideas for those. In terms of fiction, I might flirt a bit with noir or the thriller genre, always with a more literary foundation. As I mentioned earlier, I’ve always been drawn to strong plots without losing nuance or depth of character. I’m someone who likes to plan ahead, so the ideas and some of the preliminary research is there. Now I just need the time to write it all down!