As an art form, fiction’s true canvas isn’t the blank page—it’s the individual human imagination. Novels and stories are imaginative interfaces. Together, author and reader create a living story-world more complete, more engrossing, and more charged with emotional meaning than the most expensively produced moving images on the highest fidelity plasma screen. Well-constructed fiction is deeply hypnotic because it offers an intensely vicarious experience: the experience of another consciousness journeying through vivid landscapes and cityscapes, exploring new societies, confronting powerful antagonistic forces, yearning, searching, reacting, reflecting, falling in love, and dealing with all the stresses and difficulties that come with good storytelling. A vibrant inner landscape is something fiction can offer far more fulsomely than any other narrative art, which is the reason novels and stories will never be fully supplanted by movies or TV or video games. Fiction is irresistible because it offers the reader a defamiliarized version of the universal mind, in all its wisdom and agony and strange, conflicted beauty.

For ficti on writers, this is where it gets fun. The inner landscape is our native domain, and we have certain freedoms and privileges within it that are not readily available to other artists. Our stories unfold primarily as refracted through our characters’ minds, meaning that we’re uniquely positioned to push against the outer limits of objective reality. We can play around with space and time and perception in really interesting ways—including via dreams, visions, and hallucinations.

on writers, this is where it gets fun. The inner landscape is our native domain, and we have certain freedoms and privileges within it that are not readily available to other artists. Our stories unfold primarily as refracted through our characters’ minds, meaning that we’re uniquely positioned to push against the outer limits of objective reality. We can play around with space and time and perception in really interesting ways—including via dreams, visions, and hallucinations.

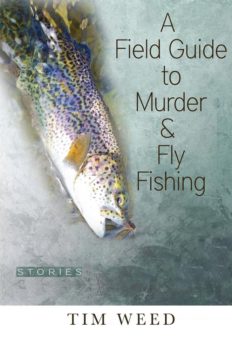

As it happens, these elements have often reared their uncanny heads in my own fiction. Dreams and visions are central to the storyline of my first novel, Will Poole’s Island, in part because I was immersed in the clashing worldviews of English and Indians in seventeenth century New England, which tread common ground only in that they both were permeated with the visionary and the unseen. But my fascination with the subject goes beyond historical research: At least six of the thirteen stories in my new collection, A Field Guide to Murder & Fly Fishing, contain dreams, visions, or hallucinations.

Some time ago I co-directed an international writing program in the course of which two of my colleagues, prize-winning writers and eminent creative writing professors both, stated authoritatively that dreams have no place in fiction. Ever. This pronouncement coincided with the above realization about my own work, so my first reaction, naturally, was one of existential panic. My second reaction was to revisit some of my favorite works of fiction to see if the pronouncement held true.

Imagine my relief when I returned to the opening pages of what is in my opinion one of the greatest novels of the twenty-first century thus far: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road:

In the dream from which he’d wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Their light playing over the wet flowstone walls. Like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast. Deep stone flues where the water dripped and sang. Tolling in the silence the minutes of the earth and the hours and the days of it and the years without cease. Until they stood in a great stone room where lay a black and ancient lake. And on the far shore a creature that raised its dripping mouth from the rimstone pool and stared into the light with eyes dead white and sightless as the eggs of spiders. It swung its head low over the water as if to take the scent of what it could not see. Crouching there pale and naked and translucent, its alabaster bones cast up in shadow on the rocks behind it. Its bowels, its beating heart. The brain that pulsed in a dull glass bell. It swung its head from side to side and then gave out a low moan and turned and lurched away and loped soundlessly into the dark.

It’s probably a good thing McCarthy didn’t submit this for critique in a writing workshop, because without the dream at the center of its harrowing opening pages, The Road would be a less powerful novel. The fact is, fictional dreams can be awkwardly written, obvious, and contrived, but when they’re well wrought, defamiliarized, and organic to the story, they can capture a character’s inner experience with stunning effect.

The same can be said for fictional hallucinations. Consider this passage from Denis Johnson’s great short story “Emergency,” from a scene in which two mind-altered friends are in a snowstorm:

The only light visible was a streak of sunset flickering beneath the hem of the clouds. We headed that way.

We bumped softly down a hill toward an open field that seemed to be a military graveyard, identical markers over soldier’s graves. I’d never before come across this cemetery. On the farther side of the field, just beyond the curtains of snow, the sky was torn away and the angels were descending out of a brilliant blue summer, their huge faces streaked with light and full of pity. The sight of them cut through my heart and down the knuckles of my spine, and if there’d been anything in my bowels I would have messed my pants from fear.

Georgie opened his arms and cried out, “It’s the drive-in, man!”

“The drive-in . . . ” I wasn’t sure what these words meant.

“They’re showing movies in a fucking blizzard!” Georgie screamed.

“I see. I thought it was something else,” I said.

Notice how the passage straddles the borderline of exterior and interior experience, which is precisely the realm of the most powerful fiction.

Visionary fiction doesn’t have to be wild or fantastic; it can be quotidian, like the images our mind sometimes creates for us under the influence of deep-seated emotions. Think of Johnson’s Train Dreams, when the protagonist, in the aftermath of his accidental participation in the attempted murder of a Chinese railroad worker, has an “almost” supernatural experience: “Walking home in the falling dark, Grainier almost met the Chinaman everywhere. Chinaman on the road, Chinaman in the woods. Chinaman walking softly, dangling his hands on arms like ropes. Chinaman dancing up out of the creek like a spider.”

Visionary fiction doesn’t have to be wild or fantastic; it can be quotidian, like the images our mind sometimes creates for us under the influence of deep-seated emotions. Think of Johnson’s Train Dreams, when the protagonist, in the aftermath of his accidental participation in the attempted murder of a Chinese railroad worker, has an “almost” supernatural experience: “Walking home in the falling dark, Grainier almost met the Chinaman everywhere. Chinaman on the road, Chinaman in the woods. Chinaman walking softly, dangling his hands on arms like ropes. Chinaman dancing up out of the creek like a spider.”

What all these passages have in common is an unsettlingly accurate “slant” portrayal of essentially dark human emotions. It’s a portrayal that draws its power from the Shadow region of the collective unconscious, the region Carl Jung identified as the source of nightmares, fairy tales, and myths. Fiction offers us the kind of direct and extremely personal access to this region that simply isn’t available via more “on the nose” narrative arts like film or television.

Because of our medium’s comparative advantage in projecting the inner landscape—because we’re creating our storyworlds from inside our characters—dreams, visions, and hallucinations allow us to capture aspects of the human experience that no other medium can.