I used to move around when I read short story collections, reading the first story in the café, then the next few in front of the Ferry Building before riding BART into the Mission, and finishing the last stories while gulping down a burrito at Pancho Villa. Then something happened—it seems petulant to blame graduate school here—and I started reading collections straight through, ticking each story off mentally as I finished it. Spending time with Chris Adrian’s stories, though, made me walk around again, made me restless, brought out my wanderlust.

I used to move around when I read short story collections, reading the first story in the café, then the next few in front of the Ferry Building before riding BART into the Mission, and finishing the last stories while gulping down a burrito at Pancho Villa. Then something happened—it seems petulant to blame graduate school here—and I started reading collections straight through, ticking each story off mentally as I finished it. Spending time with Chris Adrian’s stories, though, made me walk around again, made me restless, brought out my wanderlust.

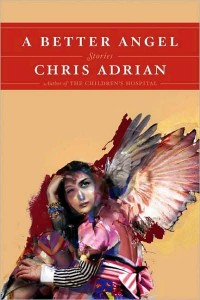

A Better Angel (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008), Adrian’s third book and first collection, turned me into a pure Reader again, instead of a Writer Who is Reading. People who take writing seriously don’t like giving that position up; after training yourself to look at your own work critically, it can be hard to relinquish that authority, to let a book speak its piece without mentally tallying the Latinate words or repeated sentence structures. But when a book earns its authority and does not abuse it, when the writer keeps his eye trained on what is good and true in addition to what is smart and beautiful, then we are required not only to read but to think, and we are awakened to the reality that it is only once a book is closed that the real work of coming to terms with the beauty and brutality of the world can begin. These stories moved me, literally.

The nine stories in A Better Angel concern themselves primarily with the intersection between private and shared trauma—understandable, considering Adrian’s profession as a pediatric oncology specialist/divinity student—and the manner in which human beings first choose to knowingly do evil. There are three stories, for example, that refer to 9/11. The first shows a religious community, alive long before the Trade Center was built, afflicted with visions of the towers being hit, burning, collapsing. The second involves a child possessed, it seems, by the souls of those killed on 9/11, through whom the murdered demand the child’s father make a sacrifice commensurate with the sacrifice made by those that died that day. The third—the last story in the collection, and by far the most disturbing—follows a teenage loser as he learns he is the child of the Devil and begins to adapt to that role; his neighbor and guide, another teenager, lost her father in the attacks, and it is her grief that pushes her to embrace her own destructive impulses. Adrian’s stories are idealistic, relentlessly imaginative and existentially harrowing—(Flannery O’Connor/Lorrie Moore) x Kafka=Chris Adrian. Using a unique mixture of shocking imagery and surprising tenderness, they illuminate the pathologies of the trauma-battered, those stricken by grief or illness who choose to funnel their angst into healing or annihilating activities. The results are individual, startling, and luminous.

While the repeated elements of Adrian’s stories never grate, the author does seem concerned with a somewhat narrow set of circumstances. There are lots of hospital scenes, lots of children making bad decisions, lots of survivor’s guilt. But after putting down this collection, we are finally thankful for Adrian’s obsessions, which seem to afford him the stamina to record, and thereby de-anesthetize us to the nearly overwhelming amount of suffering that surrounds us every moment of our lives.

Further Resources

Read excerpts from A Better Angel: “A Better Angel” in the New Yorker and “The Sum of Our Parts” in the New York Times.

Here is Bookslut’s 2008 interview with Adrian.

McSweeney’s site offers an introduction to Adrian’s second novel, The Children’s Hospital (McSweeney’s, 2006), and the publisher’s own interview with the author. You can download an excerpt from the novel here.

Read about Adrian’s debut novel, Gob’s Grief (Random House, 2001) here in RH’s Bold Type; there is also a link to an interview with the author and one of his short stories, “Every Night for a Thousand Years.”