“Now he was the one smiling. He knew they were all around the table, he could feel their eyes on him—The One With The Flat Face, The One With The Big Ones, The One With The Worried Face, The Gringo With The Ugly Finger, The One With The White Pants, The One With The Net On His Head—staring at him and waiting for his next move.”

There is so much more to Don Fidencio Rosales, the ninety-one year-old protagonist of Oscar Casares’s comedic and heartening first novel, Amigoland (Little, Brown 2009), than simply his age. First and foremost, there’s his obsessive fascination with his family’s tragic past. As he sits in his nursing home, Don Fidencio often recounts to himself the mythic tale of how his grandfather had “come to this country with the Indians. Yes, real Indians! Indians on horses! Indians with bows and arrows!” A daydreamer when it comes to stories from his family’s past, Don Fidencio is also keen about the world of the present, even as his memory fails him and his body slows down. He maintains a tough attitude, taking many of aging’s indignities in stride. He’s also very much alive, the kind of guy who will let you know if you’re beating around the bush and demand you say it to him straight.

There is so much more to Don Fidencio Rosales, the ninety-one year-old protagonist of Oscar Casares’s comedic and heartening first novel, Amigoland (Little, Brown 2009), than simply his age. First and foremost, there’s his obsessive fascination with his family’s tragic past. As he sits in his nursing home, Don Fidencio often recounts to himself the mythic tale of how his grandfather had “come to this country with the Indians. Yes, real Indians! Indians on horses! Indians with bows and arrows!” A daydreamer when it comes to stories from his family’s past, Don Fidencio is also keen about the world of the present, even as his memory fails him and his body slows down. He maintains a tough attitude, taking many of aging’s indignities in stride. He’s also very much alive, the kind of guy who will let you know if you’re beating around the bush and demand you say it to him straight.

But in the interest of fairness to Oscar Casares’s impressive and comedic characterizations, it must also be said that Don Fidencio is a grump, a first-rate crank, doggedly insistent when it comes to having things done his way. Bad behavior at Amigoland, the nursing home in which he resides in Brownsville, Texas—also the site of the short stories in Casares’s debut collection, Brownsville—has given Don Fidencio something of an iconoclast’s reputation. Among the measures of resistance he has tried: smoking cigarettes, walking without his walker, skipping lunch, and refusing the compulsory bib during dinner. Casares spends much time early on in the novel creating the social milieu of Amigoland, but he captures its essence vividly.

Casares’s novel also follows the story of Don Celestino, Don Fidencio’s estranged younger brother, who lives close to the border in Brownsville as well. Don Celestino, a retired hairstylist, is currently dating his housekeeper–the virtuous, family-oriented divorcee, Socorro. Following Socorro’s urgings, the two brothers soon reunite and, over time, re-form a bond that eventually culminates in Don Celestino helping Don Fidencio break free from Amigoland’s throttlehold. What follows is a fast-paced, exciting road-trip novel involving the two brothers and the force that brought them together, Socorro. Their journey serves as a kind of self-examination for each character; and also reminds us of the evanescence of family stories, considering that the Rosales family mythologies will die with these two brothers.

Casares’s novel also follows the story of Don Celestino, Don Fidencio’s estranged younger brother, who lives close to the border in Brownsville as well. Don Celestino, a retired hairstylist, is currently dating his housekeeper–the virtuous, family-oriented divorcee, Socorro. Following Socorro’s urgings, the two brothers soon reunite and, over time, re-form a bond that eventually culminates in Don Celestino helping Don Fidencio break free from Amigoland’s throttlehold. What follows is a fast-paced, exciting road-trip novel involving the two brothers and the force that brought them together, Socorro. Their journey serves as a kind of self-examination for each character; and also reminds us of the evanescence of family stories, considering that the Rosales family mythologies will die with these two brothers.

Casares’s skillful narration, unified in its shifting attention between each character, tells the tale of growth for each of the two brothers, and it does so without overstating the tragedy or comedy inherent in their lives. Casares seems very much at home in the world of his characters, melding the past with the subdued “Odd Couple” act on the road. The portrait of the brothers acts as a nice work in contrasts: on one hand, we have the aging postman, worried about getting the facts of history right, and on the other, his brother the hairstylist, concerned with appearances and being well liked. The brothers are also markedly different in their attitudes toward the story of their grandfather’s abduction by a band of Native Americans. Don Celestino believes that the incident rings of historical myth, while Don Fidencio seeks in the story a key to understanding himself. The family stories he carries close to his belt—and the idea of a past he shares with others—possess the power to give him salvation from the lonesomeness that ails him. Don Fidencio’s departure from Amigoland, the place where, ironically, he had been marooned without a friend in the world, forces him to play an active part in continually unfolding history. Overall, Casares keeps this thread of the novel from being too showy or dry by making the story a layered one that comes back in fragments to Don Fidencio.

The journey these characters take is, for the most part, not a tragic one. But tragedy is not the name of this game: Casares constructs an uplifting tale rather than one that is desperately melancholic. We do get glimpses and snapshots of little indignities, but the author protects Don Fidencio from appearing in a starkly pathetic light to the reader. One is left with the feeling that Casares could have upped the gravitas factor while still retaining the novel’s atmosphere. The novel also could have afforded to build even more on its earnest interweaving of past, present, and future by delving further into the brothers’ lives before the journey, in order to see the trip as true deliverance, one that rescues them both from their former lives.

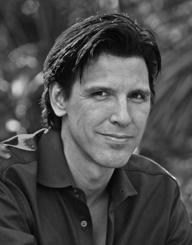

Oscar Casares / photograph by Marsha Miller

Don Fidencio’s grievances run deeper than the shame he feels about living in the nursing home. His greatest fear is not a fear of death, but rather a fear of dying in Amigoland. Don Fidencio longs for a chance to uncover more of the mystery behind his grandfather’s tales, which have begun to lose their firm place in his memory. The names of all of the folks at Amigoland have also left Don Fidencio, who has adapted by developing nicknames based on people’s most repetitive acts or particularly distinguishing characteristics. Part memory aid, part angst-ridden decisiveness, and part survival technique, all people appear to Don Fidencio as some version of “The one with…” For instance, we meet an Amigoland resident who continually talks about his days working for Pan Am (“The Gringo With The Ugly Finger”) and another resident who remains too sick to leave his room (“The One Who Cries Like A Dying Calf”).

Casares’s tremendous talent and attention toward characterization and action prevent this novel from becoming a solemn meditation on mortality. Despite what one may expect from its initial scenes, the book is not solely about decay; in fact, its plot follows a pattern more clearly reflected in the bildungsroman. The institutional life of the nursing home eventually, and almost miraculously, forces Don Fidencio back into the world again. As in a classic coming-of-age tale, this character sets off on a journey that tests his own beliefs and resiliencies. In the concluding chapters of Amigoland, Don Fidencio finds a new place in society. It’s an ending that, much like the rest of the novel, is satisfying–told with feeling and composure.

Further Resources:

- Read excerpts from Amigoland on the author’s website and as first published in Texas Monthly. Here (via Mostly Fiction) is an excerpt from Brownsville, Casares’s debut story collection. If you’re shopping for either book, consider ordering from your favorite independent bookstore.

- On the author’s website, you can read two of his essays: “In the Year 1974” and “Ready for some Futbol?”

- Here are some interviews with Casares: in SF Gate (2009); Latino Books Examiner (2009); at Art&Seek on Think TV (video); and on Bookslut (2003).