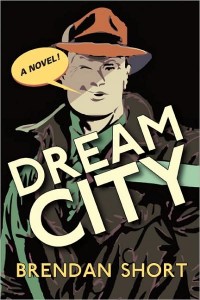

MacAdam/Cage is one of those independent publishing houses that really owns the independent label, publishing brilliant work by out-of-the-mainstream artists: Rose of No Man’s Land by Michelle Tea, the brutal masterpiece Happy Baby by Stephen Elliot. This publisher consistently puts out compelling, often risky, books. So when I received my copy of Brendan Short’s debut novel, Dream City (November 2008), and saw MacAdam/Cage’s Sexy-Angel-Award-Statue logo on the spine, I was pretty excited.

MacAdam/Cage is one of those independent publishing houses that really owns the independent label, publishing brilliant work by out-of-the-mainstream artists: Rose of No Man’s Land by Michelle Tea, the brutal masterpiece Happy Baby by Stephen Elliot. This publisher consistently puts out compelling, often risky, books. So when I received my copy of Brendan Short’s debut novel, Dream City (November 2008), and saw MacAdam/Cage’s Sexy-Angel-Award-Statue logo on the spine, I was pretty excited.

Dream City tells the story of Michael Halligan, a nervous child who finds solace in the Sunday adventure comics, where pulp heroes like Dick Tracy and the Shadow bring down the bad guys. When Michael encounters bullies or watches his parents argue, he conjures his heroes, imagining how they would save him from the myriad threats of 1930s Chicago. This defense mechanism keeps negative experiences at bay, but it also isolates him, making human connection difficult. Into adulthood, Michael flees tragedy and grief by re-reading the Big Little Books that chronicle these heroes’ adventures, cataloguing and collecting hard-to-find volumes of that series. His inaccessibility ruins his marriage and eventually traps him inside Yesteryear, the collectibles shop he opens in his father’s old gas and service station. Short tends to his themes carefully, giving each character his or her own material obsessions to ponder and pine for. As the novel progresses, we watch as people’s attachments come to dominate their lives, leaving them empty and unfulfilled in all but the most superficial ways.

The novel is separated into five sections, each from a different period of Michael’s life; underneath, a second ghost structure, which deals with the Big Little Books, serves to amplify or qualify the main narrative. When Michael’s father destroys his collection of Big Little Books, for example, this suggests the end of Michael’s relationship with his family and his childhood. As Michael recreates his collection, our concern over his attachment to the books grows into dread. After the collection’s completion, Michael’s emotional life decays, imprisoned as he is by the world of Big Littles. It’s a sophisticated technique, and Short deploys it to good effect throughout the book.

Dream City‘s characterization, however, is less sophisticated. Caricatures abound, with names like Red Walsh, Paddy Halligan, and Hard Knocks Knoll hinting at such two-dimensionality. Michael’s Asperger-y innocence disappears in the last act of the novel, a move both baffling and disappointing. Michael’s father acts like a bastard throughout the book, then receives a reprieve via materials found after his death, creating a false reconciliation between Michael and his absent parent. Michael’s wife forgives him as she leaves their home and heads for Santa Fe, a gesture both unrealistic and too familiar.

Also, the author hesitates to show many of the really difficult and dramatic scenes in the story as they occur. Here are a few compelling moments that don’t quite make it onto the page: an abortion attempt with a knitting needle, Michael’s wife’s discovery of the journal documenting his visits to prostitutes, the transformation of his father’s service station into a collectibles store. Even in the difficult scenes we do get, Short has avoided writing fully; he hurries the action along, trampling most dangerous or interesting moments. The reader gets little sense of what the process of putting a collectibles store together is like, where or how Michael learns what to buy and what to ignore. When Paddy is beaten in an arm-wrestling match by a former rival, the chapter ends with his knuckles slamming against the table. It’s dramatic, but we get no sense of what the loss means to the defeated, or should mean to us. Paddy’s assistant mechanic loses his job with employer’s death, and receives only a toolbox as compensation. Both Michael and Paddy visit prostitutes, and neither man—nor Short—spend time reflecting on the lives destroyed by the sex trade. In a novel where people walk around fantasizing they are superheroes or murderers, there is no imaginative investigation of the existences of people who get by on much less than the self-pitying protagonists of Dream City, people whose lives bend and stretch to accommodate the main characters’ mercurial desires.

There is real beauty here—in Michael’s childhood imagination, in his relationships with his mother and wife—and a voice that deserves to be recognized and encouraged. But there are significant flaws in Dream City, namely a slightly unformed feeling that makes one wish Short had committed to revising and fleshing out this novel a bit more. On the whole, however, the author should be praised for this strange and ambitious book, and MacAdam/Cage should be admired, yet again, for being a place where strange and ambitious books can find homes. Really, how many such houses are left?

Further Resources

Find out more about Brendan Short here on his website, and read “Shadows,” a short story published in the Literary Review. Also, check out this great essay on Short’s own life as a collector.