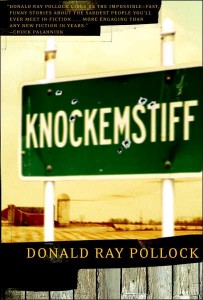

Donald Ray Pollock’s debut collection Knockemstiff begins with an epigraph from satirist Dawn Powell: “All Americans come from Ohio originally, if only briefly.” And yet, when it comes to Knockemstiff, Ohio—Pollock’s hometown and the purgatorial setting for these eighteen gritty stories—the fictional inhabitants rarely leave. Many characters who try to escape Knockemstiff end up hours later back where they started. If by some stroke of luck they do succeed in breaking free of the town, it is usually only to wind up in other, distant margins.

Donald Ray Pollock’s debut collection Knockemstiff begins with an epigraph from satirist Dawn Powell: “All Americans come from Ohio originally, if only briefly.” And yet, when it comes to Knockemstiff, Ohio—Pollock’s hometown and the purgatorial setting for these eighteen gritty stories—the fictional inhabitants rarely leave. Many characters who try to escape Knockemstiff end up hours later back where they started. If by some stroke of luck they do succeed in breaking free of the town, it is usually only to wind up in other, distant margins.

Reminiscent of Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, Pollock’s collection offers a map of Knockemstiff in its opening pages. But Knockemstiff is no quaint Winesburg. While the legend to the latter’s map notes the offices of the local newspaper and the idyllic-sounding Waterworks Pond, the Knockemstiff map starkly highlights the town dump and the dwellings of a dim-witted character named Wimpy. Although Pollock’s Ohio is darker than Anderson’s, intense loneliness and despair are omnipresent in each.

The people of Knockemstiff may be overworked and tired, but they can dream. In the title story, the unnamed narrator muses late at night about all the other Ohioans watching the same Charlie Chan movie on the local TV channel. This narrator works as an employee at the five-and-dime and lives in a trailer out back. (Picture a less self-pitying George Willard.) One day he is approached by a Californian photographer; she’s taking pictures of small town people for her book. At the same time, his unrequited love, Tina, is about to quit town for Texas with a crook named Boo Nesser. The narrator has resolved not to make a last-minute play for her: “I’ve lived here all my life, like a toadstool stuck to a rotten log, never even wanting to go into town if I can keep from it.” The story ends powerfully as the photographer takes a picture of him with Tina in front of the “Welcome to Knockemstiff” sign.

Knockemstiff’s nice guys are few, but Pollock has a knack for uncovering the whimsy and imaginative impulses behind so-called bad behavior. He locates moments of moral triumph where the reader would least expect it. Big Bernie Vickers, for instance, of the cleverly told “I Start Over,” goes to great lengths to protect his mentally disabled son from taunts at the drive-thru window at Dairy Queen; and his decent impulses are almost enough to make us forget that Bernie is also a beast who cruises town looking to pick up underage girls. In “Discipline,” a larger-than-life ex-bodybuilder pumps up his son with a lethal dose of anabolic steroids. In another tale, the drug-addicted Del dates a deranged young lady nicknamed “The Fish Stick Girl” because she carries cold fish sticks in her purse and hands them out on the street.

We may be on unsteady ground when we first shake hands with these intentionally grotesque protagonists, by the time we say goodbye, however, they are fully deserving of our empathy. Pollock also populates the collection with a few old-fashioned evil folks. Mostly men, these bruisers and blowhards successfully haunt the text and town, plucking people’s teeth out, picking fights with their wives and strangers, seducing children, and bullying others to the point of torture. Since the stories are linked, the possibility persists that these people may float back into the narrative—making the threat of tremendous violence subtle yet palpable. Knockemstiff is a place of extremity: intense rivalries and great poverty abound.

* * *

It is no surprise when a character breaks free from the town that we, as readers, are rooting for them. In these moments, Pollock manages his characters’ struggles with humor, patience, and even some tenderness. He grants them hearty doses of resiliency, even when they face tremendous odds. The outcome is often inevitably tragic, but Pollock finds ways to make us believe salvation is possible. Daniel, the teenage protagonist of “Hair’s Fate,” wants to leave Knockemstiff to get away from his father, who sawed off Daniel’s long, flowing hair and part of his scalp with a butcher’s knife – punishment for the boy’s defiling of his sister’s doll. When Daniel finally escapes the grasp of his terrible father, he faces more he bargained for with the pill-popping big-rig trucker who takes him out of town.

In Knockemstiff, many boys and teenagers are forced to contend with fathers like Daniel’s, pushed to make choices that change the course of their lives. Bobby Lowe, a recurring character at the center of three stories, is one such kid. Vernon Lowe tells his friends (and Bobby’s) that his son “shoulda been born a girl.” Bobby’s three tales are told from three different points in his life: one as a boy, one as a young adult, and one as an older man. In “Pills,” one of Knockemstiff’s most emotionally resonant stories, twenty-something Bobby and his maniacal friend Frankie dream of going to California but don’t even make it out of town. Instead, they go on a drug binge, raising bizarre if minor havoc on the outskirts of Knockemstiff. “Pills” ends with Frankie starting a fire and cooking a chicken that’s been sitting in the trunk of his car for a week; meanwhile, Bobby looks down and notices the mud on his shoes, realizing that wherever he may go, Knockemstiff goes with him.

The closest that someone comes to finding a better life occurs in “The Fights,” the final story in the collection. Here, Bobby Lowe is a middle-aged man simply trying to stay sober. The book ends as many of the stories do—with a specificity marked by openness, by a sense of possibility. It would keep us reading if more stories followed, just to see who lived around that next bend.

* * *

A few less-inspired tales, like “Schlott’s Bridge,” feel more like filler, or connective tissue; they lack the pay-off of the stronger stand-alone stories that comprise most of the book. “Schott’s Bridge” has a promising premise but falters with a premature ending. Pollack’s determination to avoid a formulaic resolution here is keenly felt as hesitation. Overall though, his stories are skillfully told and closed. You know you’re in the hands of a knock-out writer when the endings surprise as much as they resolve, as in the case of “I Start Over,” “The Fish Stick Girl,” and “Holler.” These endings are less dramatic than others, but they leave the reader with brilliant, lasting images – and with mysteries.

In a collection whose emotional spectrum keeps hitting the low notes, the moments of compassion truly shine. The finale of “Lard” is lovely, as operatic as Winesburg, Ohio’s best: in a moment of inspired heroism, the young protagonist rescues his overweight friend from the abuse of bullies. Looking into the dark night, he thinks, “He could not believe he lived there.”