Fiction writers are sometimes the first to prostrate themselves and say they don’t get poetry, but these five collections should appeal to writers across the genres. As in the previous edition of “Poetry for Prosers,” I’ve selected books that tell some kind of story or many small stories, though the plots may be absurd or cryptic or surreal–or may slip out the back door when you go looking for them. Each of the following was released in 2010.

Fiction writers are sometimes the first to prostrate themselves and say they don’t get poetry, but these five collections should appeal to writers across the genres. As in the previous edition of “Poetry for Prosers,” I’ve selected books that tell some kind of story or many small stories, though the plots may be absurd or cryptic or surreal–or may slip out the back door when you go looking for them. Each of the following was released in 2010.

[Editor’s Note: There are some differences between poems linked to in their original online forms and the newer published versions in the books themselves. All quotations are from the print collections.]

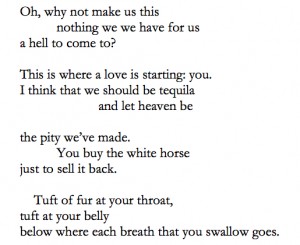

Post Moxie

Post Moxie

by Julia Story

(Sarabande Books, 2010)

No, not just because of her last name, though it does tie in nicely, doesn’t it…

These are stories of angst and the Midwest and alienation, each held still for one stunning moment in an untitled, window-shaped prose poem. I found myself getting into bed at night and reading this book, something I don’t usually do with poetry, which generally requires a daytime alertness. But I didn’t feel any need to interact with these poems, and I mean that as a compliment. I didn’t interpret them or decode them. I simply let each one arrive and depart, and it told its story exactly as I needed to know it.

And I found that to be a wonderfully unusual experience for reading a poetry book. It’s not that these poems are shallow or simple. They have great eerie depths and resonance to them. They’re just so whole. “I am not very smart at the very beginning of spring, when even the sidewalk has hormones,” writes Story. In another poem: “There are this many heads I want to break with this many bottles of Night Train, but I’m blonde and from Indiana so I look at the floor and smile.” Interestingly, for poems that feel so whole, there is an awful lot of breaking up, and not in the romantic sense. “I prefer to forgo the body altogether,” Story writes, and that’s true only in the sense that her bodies seldom are “all together.” They are usually in pieces. The body gets rearranged and moved and even mailed around. It tunnels in and out of landscapes.

Story writes in a style that many of her poetry peers have written in – she accumulates surreal images and conveys deep heartbreaks with a disaffected postmodern shrug. Yet she manages to exist in a completely naturalistic way in this style, and that’s what makes this book truly distinct and memorable.

I take my harp down to the water, but

it isn’t a harp, it’s a person and we’re

falling in love. Birds land on us and I

grip the air with my eyes. Hills are arms

and the landscape is a bucket. His whole

body is taped to me or taped to a picture

of the world.

– from “untitled”

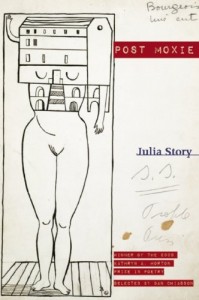

Thin Kimono

Thin Kimono

by Michael Earl Craig

(Wave Books, 2010)

It may be unfair to drag biography onto the stage, but Michael Earl Craig lives in Montana and shoes horses for a living, and these frequently seem like poems that might be spoken by someone who lives in Montana and shoes horses for a living. They are precise, cool, metallic poems, laconic and wry. They are the poems of observation and spun-off thought that might easily arise from solitary work. The language is plain, unflowery; it’s the disjointed logic of the images that turns the lines into spare poetry. The way white asparagus grows without the sun that would have made its chlorophyll surge, these poems feel like their story-lines have been cultivated in a different environment, so that there is something slightly alien and deprived about them, though you recognize their shapes. For instance, in one poem, a man at the bottom of a pool is “pretending/to be fixing a ladder” while a possibly possessed herd of synchronized swimmers practices around him. The moment has all the reverberations of a short story, but in only nine brief stanzas.

The poems of Thin Kimono are often about people in bleak situations who encounter the indifference of others, whether it’s a man whose dog won’t help him out of the snow or the speaker whose girlfriend throws him out into the night “just as one cracks open the window/of a passing sedan and pokes out/a wrapper.” Other times it’s the speaker who is unsettled but passive in response to images of violence around him–a war photo, a brutalized mannequin, a doomed robin, a stinging behind his own face “like some kind of a problem behind a billboard.” Craig blurs the line between the person confronting and the writer capturing. Feeling like “a man in a park, dripping wet with gasoline,” he is told he is merely experiencing “writer’s block.” Fortunately, nothing has blocked these strange and evocative poems from the page.

Suddenly it was time.

A single black llama ran briskly up a hill.

There was pinochle in another town.

The hungry actress ordered sea bass.

And somehow from my poem came your feeling of consent.

– from “I Was Thinking”

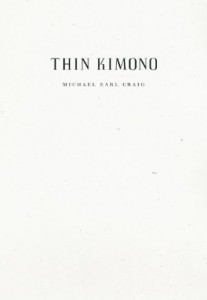

Noose and Hook

Noose and Hook

by Lynn Emanuel

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010)

Let me just say upfront that the middle section of this book is a morality play in which the main character is a dog who speaks in a baby-talk Cockney dog dialect.

OK, maybe I should have worked up to that. Please don’t go, at least not until I’ve told you that this one of the best books of poetry I can remember reading in years. Noose and Hook is recklessly brilliant, both animal and intellectual. It is about world-wearines, poetry, the self, and the way war erodes us, even from a distance. Think of the unapologetic minds of Gertrude Stein and Anne Carson, and you will have some sense of where Lynn Emanuel harkens from (even though she tries to renounce Stein in a late poem). This is her third book, and it has an advanced career quality to it. Not trying to impress, not trying to behave, it can go anywhere the poet wants, and it’s exhilarating.

Now back to that play, “The Mongrelogues.” As if the dog’s language were some sort of Middle English we might find alongside that of The Canterbury Tales, Emanuel takes up the dialect and invests her canine character with a puzzled, then trusting, then indignant take on the world that alternately shelters, abuses, abandons, scapegoats, and interrogates him. The dog’s mistress is named Mistrust, and Dogg must absorb her fate, her reaction to “middle age” and to troubled times. Dogg’s fraught relationship to his mistress is revealed in the way he calls her a speaker of “Engleash,” revealing both the language and power divide between them in one invented word. References abound – to the Bible, Berryman, Wordsworth, and Neruda (“i am tired uf bein dogg,” laments Dogg, just as Neruda’s man laments the exhaustion of being a man), to name just a few. Not unlike Shakespeare’s Caliban, Dogg becomes a kind of litmus test of humanity’s ability to be kind as it explores its own power to judge and dictate another’s fate.

Emanuel has embraced poetry’s devices–its bizarre twists, its metaphors, its music, its puns and wordplay–and yet she has written a book that might well transcend poetry and appeal to many differently tuned minds, simply because of how go-for-broke it is.

Into the clearing of…

she climbed and stoodup from the black boots of her blackouts

into her body.The coat wept upon her shoulder,

it hung upon her, a carcass heavy on a hook,and in the sockets of the buttonholes

the buttons lolled and looked.As she climbed into that clearing

it shook as it took her.A fever wrote the sentence

and screwed it tight with acheand the long hair of the grass grew silvery and weak,

lay greasily against the skull of dirt.My mother was a figure armed with…

and came toward meflew to me as though I were a sentence

that must be mended, that must be brokenthen ended, ended, ended.

– from “The Revolution”

The Madeleine Poems

The Madeleine Poems

by Paul Legault

(Omnidawn Publishing, 2010)

Trying to figure out who Madeleine is and why these poems are hers, one can’t help but think of Proust’s madeleines, the bite that evokes lost worlds, and wonder if Paul Legault wants his character of the same name to be a similar device. Yet there is nothing nostalgic in these poems, in which every title remakes Madeleine in a new form: “Madeleine as Home,” “Madeleine as Matador,” “Madeleine as New Frontier,” etc. Ultimately I tend to think Madeleine is really just a material, like carbon, something elemental, of which things are made (“a new thing/of an old thing made/anew”)… or perhaps the pioneering spirit itself, the alter ego/embodiment of wanderlust with its accompanying rudder of shame and violence.

In the only poem that’s just Madeleine in her own skin and voice, she’s just as elusive as anywhere else, announcing that she is the “Madonna of chosen things” and that she will “outlast” us. She’s also a cold and brutal presence, inasmuch as she is present at all. In the end, who she is and why she’s the vessel for these poems is perhaps the least interesting thing about the astonishing images of this book. The way Legault makes abstractions feel visceral is what’s most notable. His grim, ghostly half-history is mesmerizing, peopled with Walt Whitman and Christopher Columbus and many other personas and lands, both identified and suggested.

Though the poems can grow a bit indulgent in their withholding and sometimes circular syntax and heightened, fragmented language, they are more than saved by moments of audacious clarity, as in the poem “Madeleine as James Dean and the Whale,” when the body of the whale is described as “stone washed,” literally so, evoking Dean’s famous jeans in a flash. And even in some of the withholding and circular language, there is a purposeful feeling, something darkly sexual, acerbic, and enticing, not merely remote. “In one of the rooms, time gets really close,” writes Legault, and, with still no idea of what that could mean, you feel it.

These are challenging poems, and this is probably the book that least obviously belongs on this list, but for the adventurous reader/writer of more cerebral fiction, it offers up a great reward.

– from “Madeleine as Tourist”

American Fanatics

American Fanatics

by Dorothy Barresi

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010)

Dorothy Barresi has described her ideal poetry as “poetry that knows what it knows for only a second, and loves the brute world anyway.” I’m not sure about the fleetingness of the knowledge, but there’s no doubt about the brute world.

The title of the book tells you Barresi’s not messing around, and the first poem gets right to work, taking on religion and its slow burn into extremism in the very first stanzas. The great danger in this world is that it is made up of people who seek “a genesis wrapped/in exodus,” who believe that the better world can begin only when the competing world is destroyed. Her take on this predicament is at different moments profane, worried, questioning, brash. Through it all, God is the essential shape-shifter. “God is hammy as an old rock star,” in one poem, a “brass-knuckled, wire-tapped tough” in another.

Political poems often, with their litany-like and incurious approach, defang their subjects even as they infuse them with more growl. On the other hand, lyrically innovative poems can treat current events and anxieties as unworthy of their high-shelf beauty. Barresi, however, can discuss fanaticism head-on and then wrap her conclusions in this beautiful, vivid image: “Reading the newspapers lately, you’d think/American had been educated/In a single ray of handsome and murderous light/By which we see/individual belief is everything, being free.” She can also pause, amidst poems mostly focused on human foibles, to notice “fog mumbling along/the numbest parts of the morning’s throat” or the way turtle eggs glow “as though they had been pressed through immaculate doorlight.”

Not every poem here is perfect, but even those that don’t quite hit their stride tell us something about ourselves: whether the preening we do through diets and midlife crises or the more serious ways we confront faith, security, and responsibility. They are about looking squarely at those deciding what they’d kill for, while we decide what to live for.

Did I mention that in my catherdral a cardinal’s hat

hangs from the rafters like a tiny blood clot?

Caught up so high, so far into the brain of the thing,

that you can barely make it out?And a full ration of gently

apoplectic saints

holding their breath in the side chapels,and one priest

in elegant surplicecoming up from behind

everyone

like Groucho Marx goosing Margaret Dumont.O velvet lash of the short vowel sound

laid over a flaming poker!

to burn awake

my intentions each day

as I raise myself from the dead.

– from “It Is Good To Be Amongst Catholics Again”

Further Links and Resources

– Ordering directly from the presses is a great way to keep poetry alive and well! To order one of these books directly from its publisher, click on its title in the review.

Julia Story / photo from Sarabande

– Sarabande’s website for Post Moxie features an interview with Julia Story, writing exercises, and recommendations (from the author) for further reading. Two more poems by Story, “Bride/Beer Can” and “Glossary,” can be read at La Petite Zine. Verse Daily has also featured several poems from Post Moxie, including “From Its Plastic Light.”

– In this interview at HTML Giant, poet Michael Earl Craig talks about Thin Kimono, fudge, soundtracks, and “den wash.” At Octopus Magazine, you can read the poem excerpted above, “I Was Thinking”, and two others.

In this video, he reads “I Am Coming Over to See You” and other poems:

Dorothy Barresi

– This interview with Dorothy Barresi (American Fanatics) at Words without Borders focuses on the writer’s relationship with Los Angeles and its role in her poetry. Another interview at West Branch Wired offers a link to two of her poems that first appeared in West Branch 62. At chaparral, you can read two of her poems, “How’s the World Treating You?” and “Responsibility.”

– On the University of Pittsburgh Press’s website, read a longer excerpt from Lynn Emanuel’s Noose and Hook. Via Slate, listen to Emanuel read “The Revolution” (the poem excerpted above). Here, watch her read–backed by a full orchestra–her poem “Desire”:

Emanuel reads more poems from Noose and Hook on the Poets’ Co-op TV Show (Episode 33):

Paul Legault / photo from Omnidawn's website

– Read several selections from The Madeleine Poems on Paul Legault’s website.

Julia Guez at BOMBLOG also highly recommends this book and features an interview with Legault; find out how studying screenwriting informs his poetry and why he recently published an “English-to-English translation” of Emily Dickinson’s poems.