Architecture is the masterly, correct, and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.

Le Corbusier

Then I understood the remark that a building wasn’t finished until it had been torn down or lay in ruins.

Stamm, Seven Years

Zadie Smith called Swiss writer Peter Stamm’s Seven Years, translated from the German by Michael Hoffman in 2011, “a novel to make you doubt your own dogma.” Rosecrans Baldwin called it “ruthless truth.” It charts one man’s relationship with two women over the course of the eponymous timespan. “The beautiful one,” the narrator’s wife, friend, and co-founder of their architecture firm, plans their life the same way she designs buildings: one practical blueprint at a time. “The other woman,” the lover, is plain, religious, comfortingly ambitionless, and completely devoted to the man. He compulsively returns to her again and again “like an addict,” kicking the columns out of his wife’s design one by one. You know everything is going wrong—or right? or neither? or both?—and you know the building is coming down, and you cannot avert your eyes. In the end you stand with the narrator, blinking in the light where a home used to stand.

Zadie Smith called Swiss writer Peter Stamm’s Seven Years, translated from the German by Michael Hoffman in 2011, “a novel to make you doubt your own dogma.” Rosecrans Baldwin called it “ruthless truth.” It charts one man’s relationship with two women over the course of the eponymous timespan. “The beautiful one,” the narrator’s wife, friend, and co-founder of their architecture firm, plans their life the same way she designs buildings: one practical blueprint at a time. “The other woman,” the lover, is plain, religious, comfortingly ambitionless, and completely devoted to the man. He compulsively returns to her again and again “like an addict,” kicking the columns out of his wife’s design one by one. You know everything is going wrong—or right? or neither? or both?—and you know the building is coming down, and you cannot avert your eyes. In the end you stand with the narrator, blinking in the light where a home used to stand.

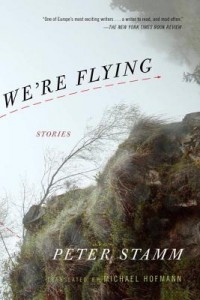

We’re Flying, the new Hoffman translation of two of Stamm’s story collections Wir Fliegen and Seerücken, is Seven Years in concentrate. Add water, have brutal insight. If the plot of Seven Years seems at risk of chauvinism and a certain kind of fashionable machismo, you should know it’s just not that simple. Seven of the twenty-two stories collected here are told in a female character’s close third point of view. And it doesn’t matter if he’s writing about a boy tucking himself between his legs in the pool shower or a woman fixated on her upstairs neighbor, Stamm renders them carefully and honestly.

In “Three Sisters,” Heidi, a reluctant housewife who years before ran from her chance at art school, obsesses over the baker girl, sketching her portrait daily, daydreaming of the “pert look of a seventeen-year-old girl with oodles of knowledge and no understanding.” She remembers how, when she was pregnant, her husband’s family “acted as though the baby was already born and belonged to them,” and now that her son is here “she couldn’t imagine a life without him, even if she did sometimes wish he had never been born.” A harsh thought, maybe, but honest.

Stamm refracts even geographical details through the characters. Each time mountains appear in a story, they’re different. To Heidi, they’re “stony sisters, that simultaneously drew her and frightened her,” while to a man returning to the village where he abandoned a woman and child, the “looming shape of the mountain” has “the body of an enormous animal that had come down ages before to lie down in the plain, and had gradually been overgrown with grass and forest.” There’s an element of Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” here. Those mountains mean something. To say that to one character they’re symbols of forbidden lust and to the other they’re specters of guilt would be uncouth, but it’s felt.

Stamm refracts even geographical details through the characters. Each time mountains appear in a story, they’re different. To Heidi, they’re “stony sisters, that simultaneously drew her and frightened her,” while to a man returning to the village where he abandoned a woman and child, the “looming shape of the mountain” has “the body of an enormous animal that had come down ages before to lie down in the plain, and had gradually been overgrown with grass and forest.” There’s an element of Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” here. Those mountains mean something. To say that to one character they’re symbols of forbidden lust and to the other they’re specters of guilt would be uncouth, but it’s felt.

Sex can be the ultimate commitment and the ultimate escape, and Stamm’s characters are often teetering between the two. A passing train calls out their name, a stranger casts a coy glance, and suddenly they want to tear down their lives and flee. In “The Natural Way of Things,” a couple has taken a trip to try and rekindle their flagging romance, but the wife ends up becoming annoyed with the neighbor’s loud children and the husband can’t stop watching the neighbor’s wife sunbathing topless. She has “small firm breasts that remind [him] of the Polynesian women in Gauguin’s paintings.” He feels a “desperate desire to go over and touch them.” The story brings to mind Tobias Wolff’s “Next Door” and Raymond Carver’s “Why Don’t You Dance?” and comes to a simultaneously crushing and erotic end.

In such calm prose, the sudden baring of genitalia stands out. When the priest in “Children of God” sees the patch of trees where a farmer brings women to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh, it looks “as if an island erupted from the land, and torn the soil aside like a curtain.” A girl has come to him claiming to be pregnant by immaculate conception. His early skepticism moves into a reluctant belief and on into lust and love. He goes to the grove of trees, strips himself bare, and stands “the way God had made him: as naked as a sign.” It’s an epiphany in the old sense of the word, not a model of the short story but an unveiling, the stripping away of pretenses. A narrative flashing. André Breton wrote that in a rigid society, “sex—which respects no barriers and obeys no laws—can at any moment become an agent of chaos.” Surrealism might be the furthest thing from Stamm—he’s more aligned with Vermeer and Rembrandt—but sex is always lurking in the corners of his canvases, ready to throw stability and morality into disarray, to push the ordered lives of the characters into chaos and change. He lets his characters stumble to the edge, to a state of literal and metaphorical and holy nakedness.

I’ve already brought up Hemingway, Wolff, and Carver, and could just as easily mention Gaitskill, but—I can’t stop myself—the closest American equivalent I can come up with is James Salter. Although Stamm is only forty-nine, he writes like a master late in his career. There’s a quiet maturity. A sure hand. Clear and direct lines. The events proceed so casually they feel inevitable, as if Stamm is simply relating them as they are. He writes like his landscape painter in “Go Out Into the Fields” paints: “out of a passionate indifference.” There are no prose fireworks, just calm and cool erosion, the gathering of silt here, the trickling away of a rock bluff there, the occasional abrupt cataclysm shaking and burning the land. The sensation, even more than architectural or geographic, is bodily. The stories form deposits in your gut. You won’t forget they’re there.

Further Links & Resources

- Stamm talks to the New Yorker about his favorite story in We’re Flying, “Sweet Dreams.”

- Read “The Natural Way of Things” in its entirety over at Recommended Reading (an online magazine by Electric Literature).

- Peter Stamm joins the editors of Granta, Tin House, and PEN America—along with contributors to those magazines—for a freewheeling conversation about the past, present, and future of literary magazines, both in the United States and abroad: