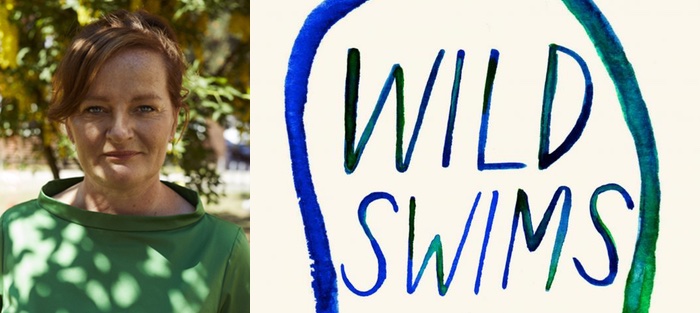

Dorthe Nors’s new collection of stories, previously published in her native Denmark and the UK, appears in the United States in the midst of the pandemic winter. To some, the stories may seem perfect for the moment; others may find the collection too dark a reflection of current isolation, rupture, and loneliness. Reader, beware.

Nors’s novel Mirror, Shoulder, Signal (Graywolf, 2016) was a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize, but her short fiction has introduced her to an international audience. She is the first Danish author to be published in The New Yorker, and her second New Yorker story, “Freezer Chest,” is included in this collection. The narrator, Mette, looks back on high school, recalling an older student, Mark, who frequently tried to humiliate her. The ultimate attempt occurred on a high school study trip: “He called me over, Mark did, and told me the story of the freezer chest.” The bully claims to have lost his “great talent” as a guitarist “because one day he’d been rummaging around in his grandmother’s freezer chest, whose hinge mechanism turned out to be broken, and just as he was standing there about to grab some cinnamon kringles, the freezer lid had slammed down on his fingers.” He pressures Mette, in front of the others, into saying she believes him, and then taunts her for being gullible. “It was as if a heavy lid had slammed shut within me . . . . I fell back into the dark and thought of things that were impervious—cement floors, plexiglass, ice packs—and that the safest way to avoid people like Mark was to seal yourself off.” She has followed that course since.

Nors’s novel Mirror, Shoulder, Signal (Graywolf, 2016) was a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize, but her short fiction has introduced her to an international audience. She is the first Danish author to be published in The New Yorker, and her second New Yorker story, “Freezer Chest,” is included in this collection. The narrator, Mette, looks back on high school, recalling an older student, Mark, who frequently tried to humiliate her. The ultimate attempt occurred on a high school study trip: “He called me over, Mark did, and told me the story of the freezer chest.” The bully claims to have lost his “great talent” as a guitarist “because one day he’d been rummaging around in his grandmother’s freezer chest, whose hinge mechanism turned out to be broken, and just as he was standing there about to grab some cinnamon kringles, the freezer lid had slammed down on his fingers.” He pressures Mette, in front of the others, into saying she believes him, and then taunts her for being gullible. “It was as if a heavy lid had slammed shut within me . . . . I fell back into the dark and thought of things that were impervious—cement floors, plexiglass, ice packs—and that the safest way to avoid people like Mark was to seal yourself off.” She has followed that course since.

The quiet, sinister power of an everyday freezer chest—both to preserve and to desiccate—is emblematic of the chill and sense of threat, sometimes verging on the blackly humorous macabre, with which Nors imbues ordinary people, events, and objects with menace. In fact, freezer chests appear in a total of three stories here. And in each of these instances, the author distorts the familiar in disquieting ways.

The narrators experience no amount of disquiet themselves. The protagonists of these intense, constrained stories, are profound solitaries in retreat from lost, failed and often cruel relationships, and sometimes their own mistakes and transgressions. Most have chosen banishment from the risks of connection, have elected solitary confinement. Nors describes the theme of her novel Mirror, Shoulder, Signal as “longing to go back to a place that no longer exists. About emancipation—and being stuck.” Longing for what or who is lost, longing for freedom, being stuck—these themes thread through Wild Swims, too. Over and over, the action these characters take is negative: renunciation, retreat, withdrawal—futile efforts to escape the pain of relationship and betrayal, the shame of self-disgust. When Emily Dickinson says, “The soul selects her own society— / Then shuts the door—” there is liberation in the chosen confinement. But when Nors’s characters select their own society and close the door, when the lid of the freezer chest slams down, the result is entrapment rather than liberating privacy.

The pressing conflict in these stories is internal, intrapersonal. Streaming parallel narratives of thought, recollection, and observation reveal snatches of the present and partial, allusive glimpses of determinative past events and interactions. Occasionally, reading these spare lines, the almost antiseptic, chronologically discontinuous narrative, one hears echoes of other distinctive authorial voices, glimpses other story worlds. A fox wanders across the field in “The Fairground” as though escaped from the pages of D.H. Lawrence. A paragraph later, the narrator recalls a final parting: “He didn’t say anything else before going out into the hallway and putting on his winter coat, it was snowing, she could see that when he opened the door.” Through that open door, for a moment, the reader glimpses the Dublin snow of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” Whether these echoes are intentional or coincidence, the effect is eerie and resonant. Nors is an innovator, and other innovators haunt her pages.

Yet despite the deeply internal conflicts of these stories, the author successfully manages to bring the reader into the interior experience of her characters, and it is often uncomfortable, not easy to bear. These people “shake with cold,” both physical and emotional, suffer the damped down, anaesthetized pain of an iced wound. Like doomed Arctic explorers trapped in ice, Nors’s characters consume self and other. Always assessing others but especially the self, their most frequent aspiration is self-erasure, to be “minimally present,” to disappear. Reading these stories at times feels almost like complicit voyeurism—witnessing pain through a one-way mirror in the laboratory of Nors’s world.

The author introduces the collection with an epigraph, drawn from the story “Manitoba”: “You can always withdraw a little further.” In retrospect, that epigraph may be read as a posted warning. These are daring, untraditional stories—which will work for some readers, and not for others. Nors eschews traditional narrative arc, does not aim for epiphany or resolution. As always, response depends on reader sensibility as well as circumstance.