Hello, blog readers! In case you’ve missed any of our features so far this month, here’s a quick rundown:

REVIEWS

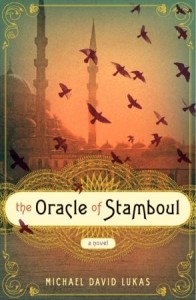

Lee Thomas reviews Michael David Lukas’s debut, The Oracle of Stamboul, recommending the novel—with its “sun-drenched marble, the heat and clamor of the bazaar, and a warm, salt breeze off the Sea of Marmara”—as an antidote to mid-winter malaise. (Yes, please!) The book features a precocious prodigy, eight-year-old Eleonora Cohen, as a guide through Lukas’s tale of political intrigue in late 19th-century Stamboul. The Oracle of Stamboul was also FWR’s March 1 Book of the Week.

Lee Thomas reviews Michael David Lukas’s debut, The Oracle of Stamboul, recommending the novel—with its “sun-drenched marble, the heat and clamor of the bazaar, and a warm, salt breeze off the Sea of Marmara”—as an antidote to mid-winter malaise. (Yes, please!) The book features a precocious prodigy, eight-year-old Eleonora Cohen, as a guide through Lukas’s tale of political intrigue in late 19th-century Stamboul. The Oracle of Stamboul was also FWR’s March 1 Book of the Week.

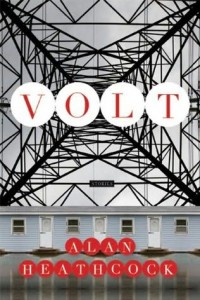

In his review of FWR’s March 8 BOTW—Alan Heathcock’s debut story collection, Volt—Tyler McMahon praises the book not only for its individual stories, but for Heathcock’s triumph at crafting a successful collection:

In his review of FWR’s March 8 BOTW—Alan Heathcock’s debut story collection, Volt—Tyler McMahon praises the book not only for its individual stories, but for Heathcock’s triumph at crafting a successful collection:The best collections, for my money, are the ones that work the form to its full advantage, turn its weaknesses into strengths, and make the stories inseparable from one another—greater even than the sum of their parts. Alan Heathcock’s Volt is one such collection. These stories are not merely chronological episodes adding up to a larger narrative. Nor does a common protagonist neatly stitch them together. Several characters do recur, but the main link between these pieces is Krafton. This fictional town is only a setting in so much as a church is a building—it’s better described as a group of people, a community.

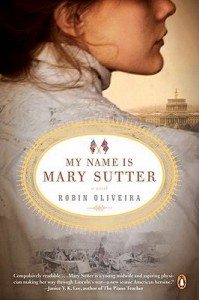

In this review, Helen W. Mallon introduces Robin Oliveira’s debut novel, My Name is Mary Sutter, “the gutsy tale of a youthful Albany, New York, midwife who becomes a nurse to soldiers of the Union Army—men who were more likely to die from now-preventable infections than they were from gunshots.” Mallon admires Oliveira’s portrayal of a heroine “hell-bent on becoming a surgeon at a time when no woman in this country had been admitted to a medical school,” praises the author’s command of point of view (which “seamlessly” shifts from character to character), and asks larger questions about how authors of historical fiction render the past as real for their readers.

In this review, Helen W. Mallon introduces Robin Oliveira’s debut novel, My Name is Mary Sutter, “the gutsy tale of a youthful Albany, New York, midwife who becomes a nurse to soldiers of the Union Army—men who were more likely to die from now-preventable infections than they were from gunshots.” Mallon admires Oliveira’s portrayal of a heroine “hell-bent on becoming a surgeon at a time when no woman in this country had been admitted to a medical school,” praises the author’s command of point of view (which “seamlessly” shifts from character to character), and asks larger questions about how authors of historical fiction render the past as real for their readers.INTERVIEWS and ESSAYS

Despite the boycott, Preeta Samarasan traveled to Sri Lanka in February for the Galle Literary Festival and found friends, eager young writers, and a love for a country that reminds her powerfully of her native Malaysia. In her essay “Four Days in Galle”, she reflects on the power of free speech in a country recovering from many years of civil war. An excerpt:

Despite the boycott, Preeta Samarasan traveled to Sri Lanka in February for the Galle Literary Festival and found friends, eager young writers, and a love for a country that reminds her powerfully of her native Malaysia. In her essay “Four Days in Galle”, she reflects on the power of free speech in a country recovering from many years of civil war. An excerpt:Yet the Reporters Without Borders petition made little sense to me on the most basic level: shouldn’t a literary festival be the last thing one should boycott in a country with a poor record of press freedom and human rights? I could see an argument for boycotting investment, or perhaps even tourism, but a literary festival? Really? Why sabotage an opportunity for free speech when they are so rare?

Where do film noir, post-communist Bulgarian fiction, and black comedy intersect? In Vladislav Todorov’s searing noir-meets-social-commentary novel, Zift. In this interview, FWR’s Steven Wingate and Todorov discuss poisonings, the resurgence of narrative fiction in post-communist Eastern Europe, the idea that “many people enjoyed spying on their neighbors” for the state, and much more. An excerpt from Todorov’s response to a question about political/historical context and Zift‘s particular resonance today:

Where do film noir, post-communist Bulgarian fiction, and black comedy intersect? In Vladislav Todorov’s searing noir-meets-social-commentary novel, Zift. In this interview, FWR’s Steven Wingate and Todorov discuss poisonings, the resurgence of narrative fiction in post-communist Eastern Europe, the idea that “many people enjoyed spying on their neighbors” for the state, and much more. An excerpt from Todorov’s response to a question about political/historical context and Zift‘s particular resonance today:Under communism novelists had to be markedly aware of their social and political environment, and [they had] to follow strict guidelines of its representation—the so-called “socialist realism.” After the fall of communism, they could engage in soul-searching, which led to the “lyrical novel.” This type of novel lacks eventful storyline and refrains from discussing social issues. The same goes for Bulgarian cinema, which at the time amalgamated personal frustrations and idiosyncrasies with folklore imagery and poetical fabulousness. Within such literary and cinematic contexts, my task was to create a type of narrative that would be both lyrical (Zift’s story is told in the form of a confession), and genre-and-plot driven (it consciously adopts the hardboiled style of noir).

In his guide for writers, How to Write a Sentence, literary theorist Stanley Fish outlines a method for improving your prose style, showing readers how to dissect and learn from famous sentences of the past. His book is concise, lucid, and eloquent. But does his method work? In this essay, Daniel Wallace puts it to the test. Here’s a taste from Wallace’s piece:

In his guide for writers, How to Write a Sentence, literary theorist Stanley Fish outlines a method for improving your prose style, showing readers how to dissect and learn from famous sentences of the past. His book is concise, lucid, and eloquent. But does his method work? In this essay, Daniel Wallace puts it to the test. Here’s a taste from Wallace’s piece:It is already a commonplace, in essays and books on the craft of writing, that if you want to write good fiction, you must be able to write good sentences. The question Annie Dillard asks aspiring writers in The Writing Life—“Do you like sentences?”—is echoed, in longer form, by Francine Prose in the early pages of Reading Like a Writer. Rick Moody, in his introduction to Amy Hempel’s Collected Stories, twice states that, “It’s all about the sentences,” a claim given poetic form by Gary Lutz, who calls the sentence the “one true theater of endeavor.” Indeed, the sentence is the most concrete unit of written prose, containing a definite beginning and end, the place where writers lay out logical connections between the parts of speech. We think in many shapes, but we write in sentences. Whatever we attempt in English prose—whether essay, tale, or recipe—unless it is unusually experimental, must be made of sentences.

In 1990, Stephanie Vaughn published her debut collection of short fiction, Sweet Talk. Critical reception was overwhelmingly positive. A reviewer for Mother Jones wrote, “There is not a weak story in Sweet Talk and few are less than spectacular […] Hers is a wise, touching, extraordinary voice—the sort rarely achieved at the end of a gifted career, let alone at the beginning.” To date, Vaughn’s first book has also been the only one her adoring fans have seen. In this new essay, “The Enduring Magic of Stephanie Vaughan’s Sweet Talk,” Forrest Anderson writes about the wonder of discovering this book in 2010. Via his essay, here’s an electric passage from Vaughan’s story “Dog Heaven”:

In 1990, Stephanie Vaughn published her debut collection of short fiction, Sweet Talk. Critical reception was overwhelmingly positive. A reviewer for Mother Jones wrote, “There is not a weak story in Sweet Talk and few are less than spectacular […] Hers is a wise, touching, extraordinary voice—the sort rarely achieved at the end of a gifted career, let alone at the beginning.” To date, Vaughn’s first book has also been the only one her adoring fans have seen. In this new essay, “The Enduring Magic of Stephanie Vaughan’s Sweet Talk,” Forrest Anderson writes about the wonder of discovering this book in 2010. Via his essay, here’s an electric passage from Vaughan’s story “Dog Heaven”:Every so often that dead dog dreams me up again.

It’s twenty-five years later. I’m walking along 42nd Street in Manhattan, the sounds of the city crashing beside me—horns, gearshifts, insults—somebody’s chewing gum holding my foot to the pavement, when that dog wakes from his long sleep and imagines me.

I’m sweet again. I’m sweet-breathed and flat-limbed. Our family is stationed at Fort Niagara, and the dog swims his red heavy fur into the black Niagara River.

NEWS

This week we were thrilled to launch our Journal of the Week program with one of our very favorite journals, One Story! Read all about it—and how you might win a free subscription to this revolutionary (and consistently awesome) journal—here.

This week we were thrilled to launch our Journal of the Week program with one of our very favorite journals, One Story! Read all about it—and how you might win a free subscription to this revolutionary (and consistently awesome) journal—here.

Never miss an exciting moment on FWR by liking us on Facebook, following us on Twitter, and—of course—visiting us at home and on the blog.