Editor’s Note: The Hopwood Room Roundtable is a weekly event in which visiting writers of the Helen Zell MFA Program in Creative Writing discuss their work and the writing life with the University of Michigan’s student body, faculty, and the local literary community in Ann Arbor.

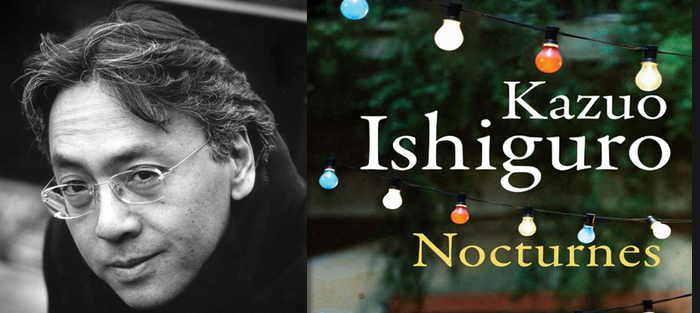

Kazuo Ishiguro’s visit to the Hopwood room last spring was the literary equivalent of Manchester United playing against Real Madrid in The Big House last summer. And although he wouldn’t have filled the 115,000 seats, the English writer did draw a crowd big enough to call for a live video stream to accommodate the individuals in the overflow room who couldn’t squeeze into the seminar where he was speaking. Peter Ho Davies, British-American novelist and former director of the U-M MFA program, introduced the man of the hour and started off the event talking about Britishness, Japaneseness, and Internationalness. And how Ishiguro saw his work in these contexts.

The author’s response drew on reviews of his second novel, The Artist of the Floating World (Penguin Books, 1986), which he said “reached for very Japanese-y metaphors…like a calm Japanese pond with tense fish underneath… sumo wrestling, samurai swords, Sony Walkmans.” He rebuffed the stereotype and said his response was to write a book containing zero Japanese people. “I would out-Brit the Brits,” he said, referring to the subsequent The Remains of the Day (Alfred A. Knopf, 1989).

The author’s response drew on reviews of his second novel, The Artist of the Floating World (Penguin Books, 1986), which he said “reached for very Japanese-y metaphors…like a calm Japanese pond with tense fish underneath… sumo wrestling, samurai swords, Sony Walkmans.” He rebuffed the stereotype and said his response was to write a book containing zero Japanese people. “I would out-Brit the Brits,” he said, referring to the subsequent The Remains of the Day (Alfred A. Knopf, 1989).

“It was a slightly scary moment because I didn’t know if I was only valued as someone who had a specialists’ knowledge. I wondered: If he’s going to do that, we’re going to fire him. We hired him to talk about Japanese people, and now he’s writing about English butlers?” As Ishiguro’s Japaneseness presumably qualified him to explain the Japanese mind to the West, his Britishness qualified him to fictionalize the already near-mythos of English butlers and country homes.

The conversation proceeded from his early work and developing style to a question about the increase of graduate writing programs in England. Here, Ishiguro entered MFA vs. NYC territory—opening one’s work to criticism in formal writing communities versus cultivating one’s talent and voice in self-made environments. The author yo-yoed thoughtfully, making arguments for both sides of the equation.

“If you’re not mature enough as a writer, there are great dangers to opening up,” Ishiguro said. “It’s a question of timing.”

But rather than continue a discussion about how best to pursue a career as a writer—after all, most of the individuals in the room were graduate students in Michigan’s Creative Writing program, and had clearly elected their path—Ishiguro was more interested in talking about matters of qualification. Ishiguro says there are too many fiction and poetry teachers in England who have no business in the business.

“It would be unthinkable to go to the Royal Academy of Music in London for piano and find that your tutor is a very good cellist who listens to a lot of piano music. But that’s what’s happening in Britain, even at a very reputable university in London that I know. I know there’s a guy teaching a fiction course who hasn’t published a novel. He’s a bright guy, but I don’t know why he’s teaching fiction at a leading university. I don’t see how you can teach fiction unless you’ve done it yourself at a very high level.”

Though I wasn’t watching, I’ll wager Peter Ho Davies received a few winks from his loyal and lucky students. Here in the U.S., the MFA teaching landscape is competitive enough to pretty much guarantee that MFA candidates work with published authors like Davies. Ishiguro’s London problem, however, calls into question the nature of the relationships between teachers, their subjects, and their students.

“In most other faculties,” Ishiguro said, “people do have to present some sort of concrete evidence of their qualifications. I don’t think it’s good enough for someone to turn up and say ‘Well I’m not a doctor, but I do it at home, so maybe I could have a job at the hospital?'”

The crowd laughed; Ishiguro continued.

“But I would extend this to other art forms. I think that if you went to an art college to study painting or sculpture, I think you’d be quite interested to know what the work of the person teaching you is like—how you received the guidance and instruction would be heavily conditioned by what you thought about the person’s work.”

For Ishiguro, teaching fiction, or teaching any other art form for that matter, requires more than knowledge. It requires experience.

For years, while playing soccer in amateur leagues in Italy, Arrigo Sacchi worked as a shoe salesman. In 1987, as the newly hired manager of Italy’s perennial soccer powerhouse AC Milan, he won the Serie A title—the Super Bowl of Italian soccer. In 1989 and 1990 his side won back-to-back European Cups—a feat no club has pulled off since. And in 1994 he coached the Italian National Team to the World Cup final—the team fell to Brazil on penalties in Pasadena. But among Sacchi’s achievements in the game, playing soccer professionally cannot be counted. In 1987, when he took the helm at Milan, many fans and critics questioned this gap in his resume, echoing Ishiguro’s sentiment about quality teaching requiring a high level of first-hand experience. Sacchi’s response: “I never realized that in order to become a jockey you have to have been a horse first.”

I asked the author about this quote and how it related to his thoughts on the relationships between teachers, their subjects, and their students (or in Sacchi’s case: a coach, the game, and his players).

“I accept that there may be exceptions that someone could be a great teacher of writing without having been published, but I don’t know about this comment from this Italian guy. Surely that misses the point. Horse training is different from being a horse. And being a soccer coach is a very different activity from teaching.”

It’s true. Sacchi’s analogy, though amusing and simple, doesn’t exactly add up. Being a soccer player, like being a coach or a teacher or a writer or a horse trainer—let alone a horse—is an individual experience. Being a soccer team, however, is a collective experience. If Sacchi were a tennis coach or in any other one-on-one coach-athlete relationship, perhaps his analogy would work.

“You don’t take swimming instructions from someone who can’t swim,” Ishiguro continued, and the crowd lit up.

“I actually wrote a short story about this, which I published in my previous collection (Nocturnes, Alfred A. Knopf, 2009). The story is called ‘Cellists.’

It’s about a young, promising cellist who is coached by an older woman who he believes is a famous cellist over the course of a summer in Italy. And she really inspires him. He feels he’s getting better and better, but over time he begins to suspect that the woman can’t play the cello at all. And that changes things for him.”

On the other side of things, while being an accomplished writer might give a teacher of writing professional experience to draw from, it does not guarantee the teacher success in teaching. Great writers are not necessarily great teachers. In fact, the two professions can be in conflict. While good writers progress through hard work and experience, they need time, first to develop their craft and then to create and promote their product, which can be an utterly isolating endeavor that leaves little room for other pursuits. Good writing teachers dedicate a selfless amount of time to their students, reading manuscripts, anticipating questions, listening, and providing thoughtful feedback—all of which can leave little time for their own writing. To find the balance can be a challenge, and some good teachers no doubt sacrifice a few of their own books along the way in order to help others write theirs.

On the other side of things, while being an accomplished writer might give a teacher of writing professional experience to draw from, it does not guarantee the teacher success in teaching. Great writers are not necessarily great teachers. In fact, the two professions can be in conflict. While good writers progress through hard work and experience, they need time, first to develop their craft and then to create and promote their product, which can be an utterly isolating endeavor that leaves little room for other pursuits. Good writing teachers dedicate a selfless amount of time to their students, reading manuscripts, anticipating questions, listening, and providing thoughtful feedback—all of which can leave little time for their own writing. To find the balance can be a challenge, and some good teachers no doubt sacrifice a few of their own books along the way in order to help others write theirs.

Though there are certainly ways in which their goals are aligned. One of my former writing teachers required Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird. Lamott says, “A writer always tries… to be part of the solution, to understand a little about life and to pass this on.” In this sense, writing fiction and teaching are different skillsets with the same end goal: to explain and make sense of the world.