My big mouth got me into a tiny amount of literary hot water recently by saying that the invention of the story collection might be the worst thing to ever happen to the short story.

My big mouth got me into a tiny amount of literary hot water recently by saying that the invention of the story collection might be the worst thing to ever happen to the short story.

Ever since, I’ve been trying to explain myself. I love short stories; some of my favorite—and certainly most influential—books are collections. It’s a form I write, teach, read, and defend. But I’ve also bought too many collections—frequently debuts—that contain one or two mind-blowing stories (often pieces that appeared in the New Yorker or the Atlantic) along with everything else the author has written to date. It bugs me when zealots claim (quite rightly) that the short story is the ideal fictional form for the digital age, and in the next breath berate the publishers of paper books for neglecting it. By far, my biggest beef with story collections is this: As a lover of books, I want them to be bound together by more than just the individual who wrote them.

The best collections, for my money, are the ones that work the form to its full advantage, turn its weaknesses into strengths, and make the stories inseparable from one another—greater even than the sum of their parts.

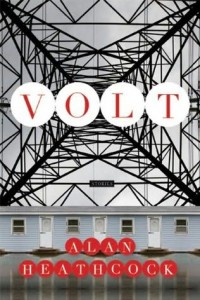

Alan Heathcock’s Volt (Graywolf, 2011) is one such collection.

Alan Heathcock

These stories are not merely chronological episodes adding up to a larger narrative. Nor does a common protagonist neatly stitch them together. Several characters do recur, but the main link between these pieces is Krafton. This fictional town is only a setting in so much as a church is a building—it’s better described as a group of people, a community.

Krafton is small-town America: Anywhere, USA. It’s the land of steak and sweet corn, pick-ups and picture shows. It is a place where Sheriff and Preacher are the most important offices, where hard work and humility are prime virtues, vanity and arrogance are cardinal sins, shame and silence are the minimum sentence, and forgiving and forgetting remain mostly aspirations.

As that description might imply, this is a book about morality—American style. But it’s a morality that is complex, overlapping, and devoid of tidy judgments. Krafton is like the rest of the country, in that if you pull away at any layer hard enough, you’ll find a raw blister of violence lurking below.

Heathcock’s third-person narrator has the big heart and bright socks of a Garrison Keillor, but the bad liver and hard knuckles of a Raymond Chandler. The prose moves like an old flatbed down a one-lane road: with confidence, with wisdom, and with a trail of meaning drifting skyward in the mind’s rear-view mirror. It is the poetry of bowling balls through shop windows—of freedom, of consequences, and of beautiful sounds.

Volt never tries to be a novel, never tries to be an anthology of the author’s own greatest hits. In a manner that is equal parts Picasso and Tarantino, Heathcock uses the fragmented nature of the collection to fracture the reader’s lens. He lashes his Kraftonians together into a kind of multi-limbed, multi-brained protagonist. We walk a mile in the shoes of victims, of perpetrators, and of bystanders.

As with Dubliners or Jesus’ Son, to read these pieces in isolation wouldn’t do them justice. To read Volt is to read a master of not only the short story, but of the collection.

Further Links and Resources

– “Fort Apache” (Zoetrope All-Story)

– “The Founding” (Five Chapters)