Alden Jones is a self-proclaimed “school junkie.” She studied literature at Brown and fiction at NYU, went on to get her MFA at Bennington, and now teaches at Emerson College and Grub Street in Boston, where she is a beloved and very highly regarded instructor of fiction and nonfiction writing. In addition to teaching domestically, Alden has worked as a student travel leader in countries as diverse as Cuba, Spain, Italy, Costa Rica, and England; she has led creative writing workshops abroad and cruised the globe as a professor for the Semester at Sea program. Having worked with them in such varied settings, Alden has become something of an expert on young Americans.

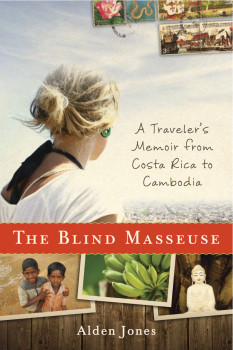

I first got to know Alden in our previous lives as leaders and directors of international student programs. Given what I knew of her experiential background it was no surprise to me, despite her training as a fiction writer, that her first book would be a travel memoir. Nor was it much of a surprise, given what I’d seen of Alden’s blazing talent as a wordsmith, that the book would make a splash: The Blind Masseuse: A Traveler’s Memoir from Costa Rica to Cambodia (University of Wisconsin Press, 2013) is the winner of the Independent Publisher Book Awards gold medal in Travel Essays. The book is currently longlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award, and is a finalist for the ForeWord Book of the Year Award in Travel Essays.

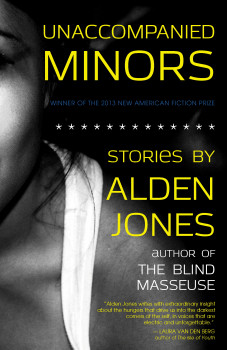

Fortunately for short story connoisseurs, on the heels of The Blind Masseuse Alden has returned to her roots as a fiction writer, and she has put her special expertise on young Americans in unfamiliar environments to excellent use. The seven stories in Unaccompanied Minors (New American Press), chosen by Kyle Minor as the winner of the New American Fiction Prize, have a boiled-down intensity, a vivid sense of being alive on the page, that is all too rare in contemporary American short fiction.

So when the opportunity presented itself to interview Alden for Fiction Writers Review, I jumped. There was a lot I’d been meaning to ask. In particular, I was curious about her experience as a writer of acclaimed collections of both fiction and nonfiction, and about the way intense and/or exotic life experiences are transmuted into narrative, both true and invented.

Interview:

Tim Weed: Your essay “Lard is Good for You” and your short story “Heathens” both appear to have grown out of an experience you had living for an extended period in Costa Rica. Can you comment on the process of transmuting your experiences abroad into narrative?

Alden Jones: After spending a year in Costa Rica as a WorldTeach volunteer, I attempted to write a novel set in Costa Rica. It was a terrible book. I was trying to say everything—about being an American abroad, about class clashes, about the hypocrisy of the Evangelical missionaries I encountered, about machismo, and so on. But the project had no focus and was a chore to read…and write. My teacher in the NYU Creative Writing Program at the time was Edwidge Danticat, one of the most patient and generous people I’ve ever known. Edwidge advised me to take a break from the novel and try to write something short and focused, with a beginning, middle, and end. I wrote both “Heathens” and “Lard is Good For You” around this time.

It’s funny that you mention them together, because I feel like “Heathens” is the story that taught me how to write a short story, and “Lard” is the essay that taught me how to write a travel essay. I obviously had a lot of material from my year in Costa Rica, a lot I wanted to explore. In each case, I said to myself, “In this piece I’m only going to write about TWO things.” In “Lard” it was lard and coffee. Every paragraph in the essay had to have something to do with one or the other or both. My feelings about being a gringa in Costa Rica, about machismo, and about my stifling host family all emerged around those threads. Same with “Heathens.” I created a character, Molly, who embodied the clueless entitlement of some American tourists in Costa Rica, and Lana, the gringa who had “gone native” and had a real bee in her bonnet about cultural insensitivity. Every paragraph in that story had to involve these two characters. The conflict in “Heathens” was instantaneous—Lana instantly had it in for poor, sweet Molly—and I almost couldn’t write fast enough to keep up with my characters.

Somehow, though I was writing from the same material, my fiction turned out much darker than my nonfiction. Seems I allow my fictional characters to go further and make more mistakes than I allow myself.

I’ve definitely experienced something similar in my own work: the fictional protagonist who is free to go places that conscience or common sense would prevent me from going in real life. Do you feel freer writing fiction or nonfiction? Is one form or the other harder or more rewarding for you?

Fiction is more mysterious to me. When people interview me about The Blind Masseuse, none of their questions surprise me. But every time I’m interviewed about Unaccompanied Minors, I learn something about my own stories. Recently someone noted that there is a lot of death in this book—I had only thought of one of the stories to hinge on a death. But there were three deaths, and one near-death that seemed in the moment like an actual death, and if something happens four times in the course of seven stories, it’s definitely a theme! Another reader pointed out that the first story in the collection was narrated from the point of view of a straight girl trying to deflect the advances of her gay friend, while the last story was narrated by a lesbian trying to seduce her straight friend. This makes for great bookends, but I was unaware of it until someone else articulated it for me. On some level I must have known these elements were providing shape to the collection, but it was 100% subconscious. In fiction I know what I believe, and what I want to discuss, but not exactly what I want to say. When I write nonfiction, I believe I have to know, when I begin an essay, exactly what the “point” is. It seems I have a pretty traditional notion of what an essay should be.

Fiction is more mysterious to me. When people interview me about The Blind Masseuse, none of their questions surprise me. But every time I’m interviewed about Unaccompanied Minors, I learn something about my own stories. Recently someone noted that there is a lot of death in this book—I had only thought of one of the stories to hinge on a death. But there were three deaths, and one near-death that seemed in the moment like an actual death, and if something happens four times in the course of seven stories, it’s definitely a theme! Another reader pointed out that the first story in the collection was narrated from the point of view of a straight girl trying to deflect the advances of her gay friend, while the last story was narrated by a lesbian trying to seduce her straight friend. This makes for great bookends, but I was unaware of it until someone else articulated it for me. On some level I must have known these elements were providing shape to the collection, but it was 100% subconscious. In fiction I know what I believe, and what I want to discuss, but not exactly what I want to say. When I write nonfiction, I believe I have to know, when I begin an essay, exactly what the “point” is. It seems I have a pretty traditional notion of what an essay should be.

One of my favorite stories in Unaccompanied Minors is “Flee,” which is set in the Tennessee wilderness and enacts the dramatic, cloistered interaction of a group of college dropouts on a kind of outdoor rehab project. In The Blind Masseuse there are several references to your past work as the leader of student programs abroad. Can you talk about how these life experiences may have affected your perspective and your writing? Is there something about a small group of young Americans plunged into an unfamiliar environment that generates storytelling energy?

Oh, God, yes! In “Flee,” these young people are stuck in the woods together with no phones, no doors to shut, no headphones to plug into, no escape from each other, plus a lot of rules they hate, like “no intimacy” and “no mood-altering substances.” And most of them are troubled going into the program, so conflict is automatic. They’re all good kids, but most of them are there to figure themselves out individually, and they hadn’t thought about how hard it was going to be to function as a community. They bicker so much it becomes almost hilarious. And of course, when you’re trapped in a small group for an extended period of time, people start to fall in love with each other…often people who would never have found each other out in the real world.

There’s also the temporary nature of these environments. As you mention, for ten years I led trips for high school students for Putney Student Travel to Cuba, Spain, France, Costa Rica, Australia, and elsewhere. On these trips, there was the intensity of the community, but also the exoticism of a new culture to contend with. I write about these environments for the same reason I’ve put myself in them so many times. It’s a heightened experience. Things are unfamiliar and exciting and you get to redefine yourself, if only briefly.

I want to go back to something you mentioned earlier: that your fiction often comes out darker than your nonfiction. What are some of the reasons for this, would you say? Do the two forms have different requirements in terms of dramatic conflict and tension, for example?

Fiction, for me, is a way to explore psychology, while essays are a way to explore an idea. Travel essays are about experience, too, of course, but in each of my travel essays I’ve tried to ask myself a question and then answer it. Why, when I was in Bolivia, did I become so attached to Coca-cola, and what did it have to do with my American identity? What are the implications of taking hundreds of pictures of the Burmese countryside through a bus window, and how does that parallel my role as an American tourist in Burma? But in fiction I go deeper into the subconscious and the way motive works. It helps that in fiction none of the characters are “me,” which you can’t escape in nonfiction!

I especially like to explore characters who think they understand their motives, when really they are after something entirely different than they think they are. But I think some contemporary fiction writers condescend to their characters this way—for example, I love Jonathan Franzen, but sometimes I wonder if he spends hundreds of pages developing a character for the purpose of exposing every single shortcoming, mining for humor at the character’s expense—and I don’t want to do that. I like to think I respect my characters, but know them better than they happen to know themselves in the particular situation in which I’ve placed them.

In “Heathens,” for instance, Lana thinks she is teaching Molly a valuable lesson, but part of her just wants to punish Molly for being a happy person. She doesn’t realize how jealous she is of Molly. But she probably will someday. In “Shelter,” Angel is doing everything to deny the fact that she’s in a situation she doesn’t want to be in—probably homeless, probably an addict, and probably a little in love with her companion, Spike. That’s where the tension is, in her denial of her situation. I’m very much compelled by the way so many human beings go through life with very little awareness of how they truly feel.

That’s a really good observation. I hadn’t articulated it that way to myself, but it completely makes sense, this idea of conflicting internal agendas, of discrepancies between conscious versus unconscious motives. It goes some way toward explaining something I’d noticed about all the stories in Unaccompanied Minors: their boiled down intensity, the highly compelling tension that animates them and makes it virtually impossible to stop reading partway through. You mentioned that in your fiction you tend to go deeper into the subconscious than in your nonfiction. Would it be fair to say, in your view, that fiction as a form is more tied to the subconscious, while nonfiction is more preoccupied with the conscious mind?

Something about authority seems important in this regard. In nonfiction, most of us are more cautious about assuming we know how other people tick, and writing about one’s own complex psychology can seem like navel-gazing. But fiction writers have the authority to go into the minds of other people. For me, that’s the fun part!

The stories in Unaccompanied Minors were written over the course of almost two decades. I wrote many things during that time, and chose the stories for the collection because I saw a theme emerging: that of young people in some kind of precarious situation. But they are also the stories that had the greatest velocity in the writing process. I wrote “Shelter” one night when I couldn’t sleep. The voice of Angel formed in my head and I had to get up and write the whole story before I could go back to bed. I wrote “Heathens,” one of the longest stories, over the course of a week; I felt myself pulled to the computer every time I had a free minute. “Flee” poured out of me with almost no punctuation. I had to go back and create sentences out of huge bricks of text. So I’m glad to hear that the velocity, the inability to stop, translated to the reading process for you.

Yes, it definitely did. For me as a reader, fiction has to have that spark, that compulsive velocity. It has to have this quality of being “truer than truth” – otherwise, why not just read nonfiction? In your case you seem to have mastered the distinctive intensities inherent to the best work in both forms, which strikes me as rare and worthy of celebration.

You’ve published both of your collections with small independent presses. How has that experience been for you, and would you recommend it to other writers?

Small presses are the way things are going for fiction and narrative nonfiction. I was thrilled to publish The Blind Masseuse with the University of Wisconsin Press. I took one look at their table at the AWP book fair and knew my book would fit right in. I approached the editor, he said to send me a proposal, and only a few months later publication was approved by the board. I had a kick-ass copyeditor who took the finest-tooth comb to every sentence and taught me how much I didn’t know about italics. The design team made three beautiful covers and let me choose which one I liked the best. Of course, the publicity piece is nothing like a New York house, and I had to do a lot of work to get the book noticed. Unaccompanied Minors is in the hands of New American Press, a very small press started by David Bowen and Okla Elliot, friends who met as graduate students. I heard about their fiction book prize, looked at the list, and liked what I saw. Throughout the publication process I’ve felt like we’re a bunch of friends working on a project together. There is no machine, nothing automatic. One night I sent David a photograph I’d taken, saying, “I keep thinking about this photograph in the context of Unaccompanied Minors. Think we can do something with it?” Ten minutes later, David sent me a new cover design integrating the photograph. I loved it. Then we went back and forth for the rest of the night tweaking it until about one in the morning. You don’t get that with a big house!

Small presses are the way things are going for fiction and narrative nonfiction. I was thrilled to publish The Blind Masseuse with the University of Wisconsin Press. I took one look at their table at the AWP book fair and knew my book would fit right in. I approached the editor, he said to send me a proposal, and only a few months later publication was approved by the board. I had a kick-ass copyeditor who took the finest-tooth comb to every sentence and taught me how much I didn’t know about italics. The design team made three beautiful covers and let me choose which one I liked the best. Of course, the publicity piece is nothing like a New York house, and I had to do a lot of work to get the book noticed. Unaccompanied Minors is in the hands of New American Press, a very small press started by David Bowen and Okla Elliot, friends who met as graduate students. I heard about their fiction book prize, looked at the list, and liked what I saw. Throughout the publication process I’ve felt like we’re a bunch of friends working on a project together. There is no machine, nothing automatic. One night I sent David a photograph I’d taken, saying, “I keep thinking about this photograph in the context of Unaccompanied Minors. Think we can do something with it?” Ten minutes later, David sent me a new cover design integrating the photograph. I loved it. Then we went back and forth for the rest of the night tweaking it until about one in the morning. You don’t get that with a big house!

Authors have to do a lot themselves these days, especially those who publish with small presses. But because most of us are in the same boat, people are enthusiastic about helping each other, and that’s good for us not only in terms of our careers, but our spirits. The camaraderie and support is genuine. Community is stronger than it was ten years ago. I feel like it’s a good time to be a writer.