Robin McLean’s Reptile House, winner of the BOA Short Fiction Prize and published this month by BOA Editions, is a book that provokes. Reptile House provokes for its style—both the attention to style and its resistance to a uniformity of style—and it provokes, most readily, for its subject matter. Bad things happen to some of the people in these stories, often at the hands of other people. In an era of television series like “Game of Thrones” and “House of Cards,” shows we love to watch because it is somehow so entertaining to watch people act unmentionably toward each other, how do we explore the motives of cruelty in a way that speaks to our actual reality? Robin McLean has, it seems, written these stories to find out.

I recently met Robin at the Associated Writing Programs Conference in Minneapolis, where we were on a panel together. I was curious about my reaction to her personally: she was friendly, generous, positive, instantly likeable. How did this cheerful person match up with what I’d read about her forthcoming book, described in such adjectives as “dark” and “disturbing” and “harrowing”? After begging an ARC off of BOA Editions and diving into the stories, I realized I wasn’t going to solve this mystery until I’d read deep into the book. Reptile House is not a book that provides all the answers. Much like the work of Flannery O’Connor or Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, the stories in Reptile House show you what happened; you, the reader, must reconcile the “darkness” of the stories with the big-hearted, big-picture worldview of the author who wrote them. I thus consider it a great privilege to be able to ask Robin some of my burning questions and to have her answer them here.

Interview:

Alden Jones: Reptile House is your first book, and you’ve previously had careers as a lawyer and a potter. In your early life you were a figure skater, and you mention in your backstory that “crashing on ice prepared you for writing fiction.” Can you tell us a little more about what that means?

Robin McLean: I feel most of my most important traits as a person/writer can be explained by my years as a skater. Falling: if you want fly and land a double axel, you have to crash and crash and crash first. Crashing is not failure in the journey to a double axel. There is no other way. You must fling yourself, jump as high as you can knowing you will crash, get up, and repeat, all in the hope that someday, after some bruising, you will land on a deep soft knee, on one strong flowing edge—beautiful. This landing, when it happens, feels simple, inevitable, and also ecstatic. It is why skaters skate—one of the reasons—that high when you’ve matched your body with the forces of physics, the forces that turn the planets, etc. It’s just so cool! Perhaps less grandly, I feel that all the good stuff I have ever written has come through a very similar process of failure. I write lots and lots of junk, botched efforts at something wonderful, endless revisions even to get the right tone for a story or to put the correct character in charge of things. But I have found that if you can live with the junk for long enough, revise and revise to less terrible, tinker until arriving at ok, maybe at some point you get to wow, that was nice. There can be a tingle in the body, a little ecstasy, in getting a story right. I recently finished a story that I’ve been trying to make work since 2005. So I guess crashing on ice gave me confidence in failure as a physical process that has many non-physical applications.

This sense of revision really shows in your sentences. When I started reading “Cold Snap,” the first story in Reptile House, I was taken in by the sentences before I had any sense of where the story was going. They are so highly polished they seem physically hammered. I feel like you’ve been able to translate some of the qualities of the plastic arts into your writing! One of the things I note about your prose is how economical it is, and how carefully the verbs are chosen. You cut to the chase: “His beard was ice” or “The dogs chased the cups that cartwheeled away.” Do you find that, during your revision process, you take out more than you add in?

I do think of stories as sort of sculptural, so it’s interesting and fantastic that you had that feeling about plastic arts. My revision process is all about subtraction. I take out every word I can, squeeze and squeeze the stories, just like clay. Some stories in the collection are fuller than others, for good reason I think, but I love the “hammered” sound, that tightness, generally.

I found myself relating my experience of reading some of the stories in Reptile House to witnessing a car accident. In the best way possible, if there is such a thing! Everything seems to be going along normally, your characters are going about their daily business, having dinner with friends, riding home from a bar in a taxi, and then suddenly something explosive and life-changing happens towards the end of the story, usually because of a decision a character makes. Did you set out to disrupt traditional narrative pacing? Who are some of your influences in terms of narrative and style?

I had to think about that one. The first thing that came into my head was Chekhov. When I was working on several of the first stories in Reptile House, I was reading a lot of him and I remember getting to his story called “Sleepy.” In that story, there’s this young girl, a babysitter, taking care of a baby and she’s really tired and she is falling asleep and baby keeps crying and crying and she’s scolded to stay awake. No one cares about the babysitter, how tired she is. There are all these beautiful repetitive objects in the story, almost hypnotically repetitive to the girl and to the reader. People are talking in the background and no one treats the girl kindly and it’s very cruel world they live in. At the end, she smothers the baby. Now she can sleep. That story really shocked me. I paid attention to it. It seemed so innocuous at first then bam. I loved that. There was another Chekhov story called “Gusev” which really blew my mind. I know I was thinking of it specifically when working on some of the stories. Gusev was just this sailor dying on a ship. He was no one special and he spends the story talking to this other grouchy sailor and then Gusev dies and they drop him over board. Most people would end the story there but the story followed Gusev’s body down into the sea, underwater, and the sea, the fish and sharks, just sort of took over the story for me in the end. It felt to me like a lightning bolt: that the story’s meaning, Chekhov’s point, became compensable only when the structure forced the reader to follow the body into the sea. It was not exactly a POV shift, but it was a world shift. I was thinking of that in several stories—that to write the whole story that I was interested in, not only part of it, I would have to shift the world a bit. I found those endings either really excited editors or really bothered others. The latter group thought I’d just run out of ideas or lost control of the story. But the endings are usually the most important part to me and I did not give them up. I just worked them over, tried to listen to what was bothering the editors. I found I could appease them by changing the title or something equally useful. Chekhov gave me courage but lots of other writers do too, writers who do not care if every reader in the world “gets it” or if the symmetry is perfect. I learned in pottery that perfection is overrated. All my pots were lumpy somewhere. I named one of the characters Gustavo as homage to Gusev.

I had to think about that one. The first thing that came into my head was Chekhov. When I was working on several of the first stories in Reptile House, I was reading a lot of him and I remember getting to his story called “Sleepy.” In that story, there’s this young girl, a babysitter, taking care of a baby and she’s really tired and she is falling asleep and baby keeps crying and crying and she’s scolded to stay awake. No one cares about the babysitter, how tired she is. There are all these beautiful repetitive objects in the story, almost hypnotically repetitive to the girl and to the reader. People are talking in the background and no one treats the girl kindly and it’s very cruel world they live in. At the end, she smothers the baby. Now she can sleep. That story really shocked me. I paid attention to it. It seemed so innocuous at first then bam. I loved that. There was another Chekhov story called “Gusev” which really blew my mind. I know I was thinking of it specifically when working on some of the stories. Gusev was just this sailor dying on a ship. He was no one special and he spends the story talking to this other grouchy sailor and then Gusev dies and they drop him over board. Most people would end the story there but the story followed Gusev’s body down into the sea, underwater, and the sea, the fish and sharks, just sort of took over the story for me in the end. It felt to me like a lightning bolt: that the story’s meaning, Chekhov’s point, became compensable only when the structure forced the reader to follow the body into the sea. It was not exactly a POV shift, but it was a world shift. I was thinking of that in several stories—that to write the whole story that I was interested in, not only part of it, I would have to shift the world a bit. I found those endings either really excited editors or really bothered others. The latter group thought I’d just run out of ideas or lost control of the story. But the endings are usually the most important part to me and I did not give them up. I just worked them over, tried to listen to what was bothering the editors. I found I could appease them by changing the title or something equally useful. Chekhov gave me courage but lots of other writers do too, writers who do not care if every reader in the world “gets it” or if the symmetry is perfect. I learned in pottery that perfection is overrated. All my pots were lumpy somewhere. I named one of the characters Gustavo as homage to Gusev.

I often tell my writing students that they need to know the important facts and how the characters feel about them even when they remain untold in the story. There is a lot of mystery in your stories, a lot left up to the reader’s imagination, mainly because you show a lot of restraint when it comes to authorial opinion. Do you feel that you know exactly what happens offstage in your stories? For example, in “The Amazing Discovery and Natural History of Carlsbad Caverns,” we watch a sadistic-seeming character jump out of a car to chase a woman he’s unjustifiably angry with down an alley, and when he returns to the car no one asks him what happens and he doesn’t offer up the information. Do you know what happened to that poor girl in the orange dress?

Yes, I know what exactly happened here. I agree. The writer must know. I also think you have to convey enough information so that your readers also have a very good idea, a fear or notion of off-stage action. If their gut does not tell them what’s happening to the girl, in my opinion, the story fails. Maybe there are small details that you don’t have to consider, but for the most part, all that stuff is important.

You have actually zeroed in on something interesting about that story. I had turned in a draft to my professor that was pretty much as it is written now—except there was no chase of the girl down the alley. Nothing happened to the girl in that draft. My professor read the story and said, Ok, you are close but I was too surprised by the ending. Those guys need to be a little bit more sadistic-seeming. Ok, I said. I added the chase. We felt the chase fixed the problem, indentified the characters more fully, so that the reader could buy the ending emotionally. At least that’s what the prof said. So back to your students. No, I do not like to tell more than I have to. In a way I like to see how little I can tell and the reader still gets it. So I leave things out, maybe too much for some people. But you have to be crystal clear about what’s going on no matter if it makes the page or not.

Well, I still want to know what happened to the girl in the orange dress, but from your answer I understand it’s in my best interest not to ask—because in my gut I know.

So much of your subject matter deals with cruelty—the cruel things people do to each other, and the sometimes arbitrary nature of this behavior. Yet you obviously feel a lot of compassion for your characters as well, and your worldview seems more curious about this behavior than judgmental of it. Some readers will enter these stories and consider them “dark” because of their themes—kidnapping, assassination plots, end-of-days scenarios. What do you want your readers to take away from these explorations? What do you hope your readers will feel at the end of the book?

I hope readers feel some complicated empathy at the end of the book. Squirm a little, yes, but feel sort of happy about the squirm. That’s what I felt while writing it: Can I write this? Can I really sit still and commit this act of violence with my fingers? What does it mean about me that I did? And how do you actually explore human beings without getting into our inherent dark half? What self-respecting fairy tale isn’t really dark and violent? Think of the violence and cruelty explored in the Bible. And since when do people have such a problem with the darkness? In that vein, I sometimes wonder what it is doing to us as a culture that many of us do not go to church anymore. I don’t go to church at all though I grew up in a sort of mildly religious family—do unto other, turn the other cheek, etc. I think about how we no longer sit in a pew for an hour once a week and meditate on how we passed by that homeless person in the street without a thought, how we said that nasty thing to our sister’s new boyfriend, or how we did not call our congressman when our bombs were dropped on a wedding in Afghanistan. Yes, religion has lots of bad things appended to it that I don’t miss, but I wonder if it is one of the reasons we have become, in my opinion, so heavily invested in our own “goodness” in our current culture, and thereby more repelled, perhaps, than our ancestors were by depictions of human ugliness in art. I don’t know. Maybe readers will share some of my questions.

I hope readers feel some complicated empathy at the end of the book. Squirm a little, yes, but feel sort of happy about the squirm. That’s what I felt while writing it: Can I write this? Can I really sit still and commit this act of violence with my fingers? What does it mean about me that I did? And how do you actually explore human beings without getting into our inherent dark half? What self-respecting fairy tale isn’t really dark and violent? Think of the violence and cruelty explored in the Bible. And since when do people have such a problem with the darkness? In that vein, I sometimes wonder what it is doing to us as a culture that many of us do not go to church anymore. I don’t go to church at all though I grew up in a sort of mildly religious family—do unto other, turn the other cheek, etc. I think about how we no longer sit in a pew for an hour once a week and meditate on how we passed by that homeless person in the street without a thought, how we said that nasty thing to our sister’s new boyfriend, or how we did not call our congressman when our bombs were dropped on a wedding in Afghanistan. Yes, religion has lots of bad things appended to it that I don’t miss, but I wonder if it is one of the reasons we have become, in my opinion, so heavily invested in our own “goodness” in our current culture, and thereby more repelled, perhaps, than our ancestors were by depictions of human ugliness in art. I don’t know. Maybe readers will share some of my questions.

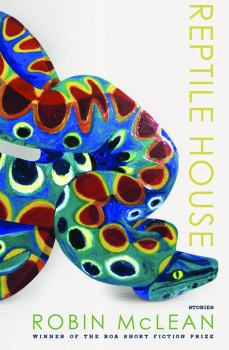

I really wanted that colorful patterned snake on the cover. Reptiles are both beautiful and threatening, familiar and utterly foreign. Similarly, we humans can design rockets to the moon, find cures for small pox, and also build gas chambers and march other beings into them. We can make divine poetry but I’m told that our most basic life functions are orchestrated by a deep down reptilian brain that has hung in there through all our evolution. I hope at the end of the book, readers feel more comfortable with our hybrid selves, part angel, part reptile, and possibly embrace the “other” in ourselves more kindly. The book helped me do that. Here’s something to think about: I’ve found since the book came out that some people cannot look at that snake on the cover. They must actually look away for the cover of the book—the snake is that repulsive to them—which is fascinating to me, a kind of cool and raw admission. Cut off the cover, I’ve said to them. Tear off the snake and just read it.