Last semester I had down time between the writing classes I teach—not enough time to go home for the leaping display of affection my dog greets me with at the door, but too much to simply sulk at the particle board desk in the corner of an empty classroom—so I went across the street to the Carnegie Art Museum. I wandered the mostly empty halls for an hour until I paused in front of an Edward Hopper painting, Cape Cod Afternoon. It’s part of their permanent collection, so I must have passed it before but something about the lighting grabbed my attention, the house’s darkened windows, the harsh, angular shadows cutting across the grass in the foreground, the weighty desolation Hopper was able to imbue such a simple scene with. Then I remembered a line on Hopper from Rolf Renner’s book, about the way he defamiliarized classic American landscapes and themes. According to Renner, Hopper’s ambiguity had “a dimension of aesthetic openness to it.” I liked that. Ambiguity. Openness. As I remembered this that afternoon in the museum, I thought of my writing, the stale clarity of it, the obviousness and consequent lifelessness, and then I thought of Catherine Lacey’s short stories. Yes, with envy, but also, and more so, with admiration, with awe.

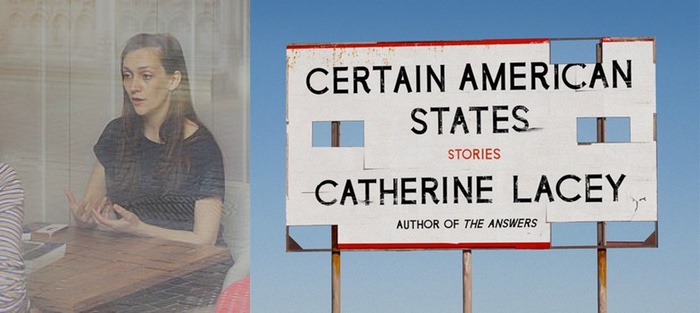

I’d read and loved Lacey’s first novel, Nobody Is Ever Missing (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014), for its claustrophobic interiority, the raw intimacy of it, her gift for long sentences that make you feel as if you’re reading them as the character is thinking them, fresh off the synaptic presses. But some of the stories in her latest collection, Certain American States (FSG, 2018), stuck with me even longer, had an outsized impact belying their brevity.

“The Healing Center,” a beautiful, enigmatic three-pager in the collection, showcases all of her skills. See, for example, the first paragraph:

Sylvia put her hands on her belly and she put her hands on her hips and she faced the mirror and she turned sideways to the mirror and she faced it again. I lowered my hands from my chest and put them on my hips too and looked into the mirror at the opposite of Sylvia and at the opposite of me, at all the flesh and hair and shapes we were living in.

The sentences run along with seven ands, the polysyndeton as beats offsetting each action, isolating it, estranging it—the prose equivalent of Hopper’s glaring, defamiliarized light. The same sort of odd lighting you find in De Chirico’s piazzas, a stylized strangeness that makes you conscious of how weird the world is, that makes you question the labels we use—words, concepts—to try to make the world comprehensible.

There isn’t much of a plot to “The Healing Center.” The story is more about a state, a condition, that plays out—or is briefly touched on, elliptically, a truth told with a steep slant—as two women meet at a healing center. The narrator is there as a patient with a problem, her diagnosis withheld aside from being called her own “never-mind moment.” The problem is an undefined anxiety, an undefinable illness.

There isn’t much of a plot to “The Healing Center.” The story is more about a state, a condition, that plays out—or is briefly touched on, elliptically, a truth told with a steep slant—as two women meet at a healing center. The narrator is there as a patient with a problem, her diagnosis withheld aside from being called her own “never-mind moment.” The problem is an undefined anxiety, an undefinable illness.

Sylvia was the receptionist for the acupuncturists, but all she did was point to a sheet of paper that said Sign Me, and I would come in and she wouldn’t look at me at all until one day she did look at me and when she looked at me, I also looked at me and I also looked at her and she also looked at herself and we both found we liked what we were looking at.

After this powerful moment of finally being seen, they move in together, walk arm-in-arm to the acupuncturist, yet just what it is they saw in one another, what it is they liked, is never spelled out. Lacey seems eager to lean into such ambiguity, but rather than put you off (if you’re receptive to just this sort of ambiguity, alive to it, in art, in life), it invites you in, allows you to make the connections—i.e., aesthetic openness.

For a time, Sylvia and the narrator are simpatico, each soothing an indeterminate ache in the other. For a time, maybe, there’s a mutual love that they can both inhabit, a healing center. Except the narrator knew all along it was—by definition?—fleeting.

I knew . . . from the first day she moved in, so it is true that I let myself break myself or maybe, rather, I let herself let myself break my self and by self I mean heart except I take issue with using that word that way, because I don’t think we have any reason to pile such a responsibility on that organ, the word of that organ. Everyone knows a heart is just responsible for filling a thing with blood, except it never fills love with blood because no one can do that because love comes when it wants and it leaves when it wants and it gets on an airplane and goes wherever it wants and no one can ever ask love not to do that, because that is part of the risk of love, the worthwhile risk of it, that it will leave if it feels like leaving and that is the cost of it and it is worth it, worth it, worth it. This is the mantra of Sylvia and this is the way she is.

The word of that organ. Though this is, at the end, attributed to Sylvia, is it not also the narrator’s view on love? Or is this view on love what the narrator loved in Sylvia? What I love is, again, the defamiliarization, the way it makes me think about the heart as an organ, as a symbol, as a word, the way Lacey circles the word, the concept, the feeling, making us see it anew, making us question what it’s supposed to signify.

Their relationship is dead, the heart stops, by the third and final page:

. . . one day in my living room Sylvia stirred her teacup but there wasn’t anything in it, so it just went clank clank, and then I knew, for some reason, we weren’t going anywhere linked-armed anymore.

It ends with a threat, with the promise of more pain to come.

Do you ever get the feeling, Sylvia asked, that you’re a lab rat?

That I’m a lab rat? That I’m a lab rat or that you’re a lab rat? Which of us?

Sylvia didn’t say anything for a minute, kept stirring the no tea in her teacup.

Who is the lab rat?

Who indeed, she said, and I said, Fuck you, Sylvia, this isn’t a fairy tale, you can’t just say stupid things like that to real people.

I’ll say it.

You won’t, I said, but she said, I will, just watch me.

Like other stories in the collection, readers might find the ending untidy, dissatisfying. Which is why, for me, Lacey’s ambiguity, her openness, is so realistic, defying the easy satisfactions of narrative arc or the centuries of adulterated dogma of Aristotle’s poetics that so often feel like suffocating contrivances, telegraphed plot points that drain blood from a story rather than infuse it. Might the very openness of the stories in Certain American States leave you dissatisfied? Yes, perhaps. And that’s exactly why I can’t stop reading them.